Just in time for India’s 75th Independence day, on August 13th, eleven wetlands were added to the list of Ramsar sites. This latest addition was a move loaded with symbolism, taking the number of wetlands of international importance in the country to 75. One among them is Thane creek, which shares shores with Mumbai, Navi Mumbai and Thane. It is the 3rd Ramsar site in the state.

To conserve the rich and biodiverse ecosystems, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands brings together member countries — which India entered in 1982 — for wise use of their wetlands. The Ramsar tag is awarded based on one or more of a few criteria, which range from a wetland’s uniqueness to its support of a significant population of a waterbird, fish, non-avian animal, or any critically endangered species.

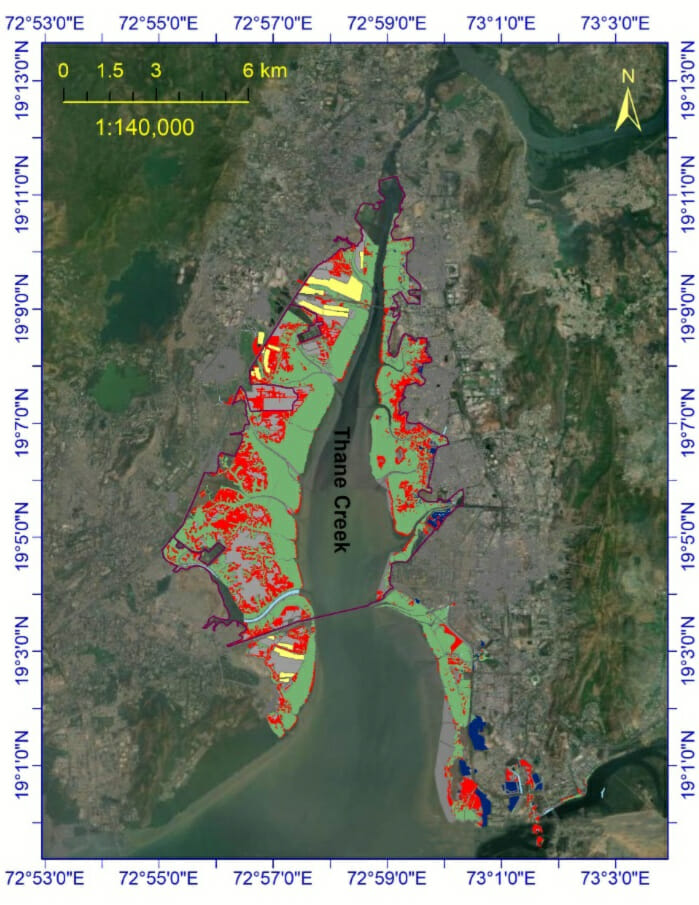

The Thane creek is no stranger to environmental glory. 17 of its 65 square kilometres fall in the Thane Creek Flamingo Sanctuary. The rest is an eco-sensitive zone (ECZ), cushioning the protected sanctuary from the urban development beyond. It provides a stop for thousands of migratory birds travelling along the Central Asian Flyway.

The creek is a refuge for over 200 species of avifauna, who flock in at strengths of around 1.5 lakh in the winter. While the flamingo may be the most recognisable, it supports the near-threatened and vulnerable species, like the lesser flamingo, black-headed ibis, painted stork, black-tailed godwit, Eurasian curlew, curlew sandpiper and Indian skimmer. 12 species of true mangroves, 39 associate mangrove species, 45 species of fishes, 59 species of butterflies and 67 insect species and more make up the ecosystem.

Thane creek’s journey to the coveted tag

Thane creek was a different place 20 years ago. Fish was abundant, flamingos were not the star attraction they are today, and environmental fame was scarce. Incidentally, this brought the creek on the radar for the Ramsar tag for the first time.

Debi Goenka, then a part of the Bombay Environmental Action Group (BEAG) and currently in Conservation Action Trust (CAT), took the lead. “The idea,” says Debi, “was to get the Thane creek on the international birdwatchers map.” The creek has always been very rich in bird life. Birdwatching could be a source of supplementary income for the fishermen.

Convincing the state government wasn’t easy, says Debi, but what clinched the deal was one crucial aspect: the Ramsar tag comes with no binding obligations for the government. The proposal went from the state government to the central government, and then to the Ramsar secretariat. The tag was a near-done deal, when the Ramsar Convention request a clear well-defined map of the Thane creek. The request for a map was passed on to the MMRDA, after which it did not progress.

After a few nudges from NGOs and unsuccessful attempts, the latest attempt began in July 2021. According to Virendra Tiwari, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, between then to August 2022, the proposal was approved and forwarded by the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests and Wildlife, the state wildlife authority, the chief minister, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and finally, the Ramsar Secretariat.

“For the want of a map, the declaration was held up for years,” says Debi.

The race to 75

In stark contrast, Ramsar sites have been added in quick succession in 2022. India had 49 sites on the list at the beginning of the year; five entered the mix on July 26th, ten were added on August 3rd, and another eleven received the tag on August 13th.

This haste in crowning the sites is no coincidence. Over a month prior, the government of India urged the Ramsar Convention to fast-track the applications in time for the 75th independence day.

“They were chosen in a hurry to reach 75 Ramsar sites in the country,” says Sidharth Kaul, president of the NGO Wetlands International South Asia, which is designated as the Ramsar communication, education and public awareness (CEPA) focal point. In its ascent, India has become the South Asian country with the most Ramsar sites.

This ceremonial use of the Ramsar tag, however, exposes how it can be used as window dressing.

“The Ramsar Convention gives guidelines to countries,” adds Sidharth. “But it is the purview of the government to put them into practice.”

According to Virendra, the Wetland Rules, 2017, are applicable on Ramsar sites. “Certain things become impermissible, like dumping debris, storing hazardous waste storage, construction, etc,” he says. But in the case of Thane creek, already a sanctuary and an eco-sensitive zone, these rules will make no additional difference.

Read more: In the destruction of wetlands, is CIDCO above the law?

How the Thane creek has changed

Despite these rules, Virendra admits, pollution is rampant in the creek. “There’s no running away from the fact that sewage is disposed of,” he says.

According to Debi, the three municipal corporations — Mumbai, Thane and Navi Mumbai — are guilty parties. Industrial effluents add to the mix. Quarrying and construction debris washes in during high tides, narrowing the depth and width of the creek. Leachate seeps from the three dumping grounds on the coast. A water analysis carried out on the river water in 2022 found Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) at 450 mg/litre, a lot higher than the permissible level of 30 units mg/litre.

For now, these changes have resulted in a thriving bird habitat.

Flamingos, in particular, have swelled to record numbers, reaching 1.4 lakh this year, taking with them the popularity of the Thane creek.

“The Thane creek is silting up quite rapidly, due to which the mudflats and the mangroves are increasing,” says Debi. “But if it continues this way, at some point there may not be any water left, which will lead to the loss of the landscape and biodiversity.“

The livelihoods of fishermen

The fishermen, whose livelihoods depend on the ecosystem, are first in the line of fire from the pollution.

Questions arose on asking the native fishermen from the Vitawa Koliwada on the east bank of the Thane creek what they thought. “What’s that?” asked one about the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the term as alien to him as the Iranian city it is named for. They had not been given the news that the land they lay claim to is now of international importance.

“They don’t even allow us to take photos of the birds with our mobile phones, and make us delete any photos we’ve taken,” says a fisherman, speaking of the disconnect between the local community and the efforts and recognition of the Ramsar tag.

Another had the perennial question: would this do anything for the dwindling catch in their part of the creek? The fishermen have many stories about an abundant and varied catch, that has near completely dried up.

“It used to be a paradise for fish,” Nandakumar Pawar, a fisherman and founder of Shree Ekvira Aai Pratishthan (SEAP), an environment and fishers’ rights group. “Now, fishermen are reluctant to go fishing because they hardly catch any. What’s the point of spending so much time trying?”

And while the increased attention on birdwatching may be another revenue, it is limited. The five government-operated boats at the sanctuary earn Rs 38 lakh annually, while five registered fishermen boats are allowed to operate from Bhandup Pumping Station. The restriction on the boats is to limit disturbance to the birds, but here, Debi mentions the speed boats run by the government do much more harm than the fishermen’s boats.

Wetland support

Opinions differ about the probable effect of the Ramsar tag, but Nandkumar is hopeful. “We are optimistic that the Ramsar tag will result in positive steps for the environment and local fishing community. The Convention doesn’t impose anything upon the government, but the government will take cognisance of the issues as it is a Ramsar site,” he says. At the very least, the tag will add to the arsenal of court cases and petitions in the National Green Tribunal (NGT) of many NGOs against the pollution and construction.

Apart from monitoring the sites, the Ramsar Convention offers scientific support for the conservation and wise use of the wetland.

In dire cases of ecological degradation, the sites can be stripped off the Ramsar Tag and put on life support.

“Sites that are not doing well ecologically are put under the Montreux record on the basis of complaints by NGOs, government or any other agency and examined,” explains Sidharth. He gives the example of Chilica Lake in Odisha, which was put back on the Ramsar site list after extensive rehabilitation in 2002.

“My worry is that if we don’t take care of these 75 sites, many might go on the Montreux Record. That would not be a very good sign for the country,” he says.