At 16, when Jency* got married to a man her family chose for her, she dreamt of a blissful life. Her husband, a carpenter, toiled to make ends meet, while she was a homemaker. Life was tough but they were content.

“During weekends, he would take us to the beach and once in a while we went to the movies. Eating Delhi appalam and walking along the seashore at Marina Beach with my husband and my two kids is one of my favourite happy memories,” she says.

That was Jency’s life in the past. The sole breadwinner of her family, she now works as a domestic help at three houses and also supplies drinking water cans in the locality. Her husband has become an alcoholic, who beats her almost every other day.

What changed in resettlement areas?

So, what led to this tragic turn in Jency’s life?

“We lived near Santhome, which was close to my husband’s workplace. In 2017, the government forcefully evicted us from our homes, saying we were living in flood-prone zones. Without prior notice, we were taken in garbage trucks one night with all our belongings and dumped in the high-rise buildings of the Semmenchery resettlement area. Little did I know then that this was the night that marked the beginning of the end of my family’s happiness,” she says.

Jency is not alone in this journey. This is the story of almost every household in the resettlement areas of Chennai. The lack of a rehabilitation plan before evictions have led to loss of livelihoods. This has taken a heavy toll on family relations, leading to increased instances of domestic violence.

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005 (PWDVA) came into effect in 2006. It provides a definition of domestic violence that is comprehensive and includes all forms of physical, emotional, verbal, sexual and economic violence, and covers both actual acts of such violence and threats of violence.

To understand this correlation between loss of livelihoods and its direct impact on families and domestic violence in resettlement areas of Chennai, Citizen Matters along with the Information and Resource Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC) conducted a Focus Group Discussion among women in resettlement areas of Perumbakkam and Semmenchery in Chennai on February 20.

A series of stories are to be published from this discussion. This, being the first part of the series, records the voices of women in resettlement areas.

Read more: Combatting domestic violence in Chennai

Life before and after in Chennai’s resettlement areas

Recalling her family life before resettlement, Mercy, a resident and a community worker in Perumbakkam, says, “Earlier we had time to speak to each other. My husband and I used to have breakfast and lunch together. Sometimes my husband, who is an auto driver, would even come back home for evening tea because there was an auto stand nearby.

Speaking on how this quality family time (even if it was for a few minutes during the day) has changed after coming to Perumbakkam, Mercy says that her daughter and her husband leave home at 7 am and come back by 9:30 pm or even later some days. “They only have time to sleep to get the next day started. This often leads to a lot of miscommunication between me and my husband. I have to ask him to take a day off if I want to discuss a family issue with him. This means that we will have to compromise on a day’s income to talk to each other like a normal couple.”

How loss of livelihood leads to domestic violence in Chennai’s resettlement areas

Loss of livelihood also increases the vulnerability of women to varied forms of abuse at home in the resettlement areas of Chennai.

After coming to Semmenchery, Jency’s husband could not find a regular job. Eventually, their family life deteriorated. “For the first few months, we tried to manage by selling the little gold and other items we had. Over the years, our lives got worse. The first time he came home drunk, he cried to me saying he wasn’t ‘man’ enough to look after his family. Then, drinking became his habit and he turned extremely aggressive. He not only started beating me up but also my children.” This gave Jency no other option but to take up the family responsibilities on her shoulders.

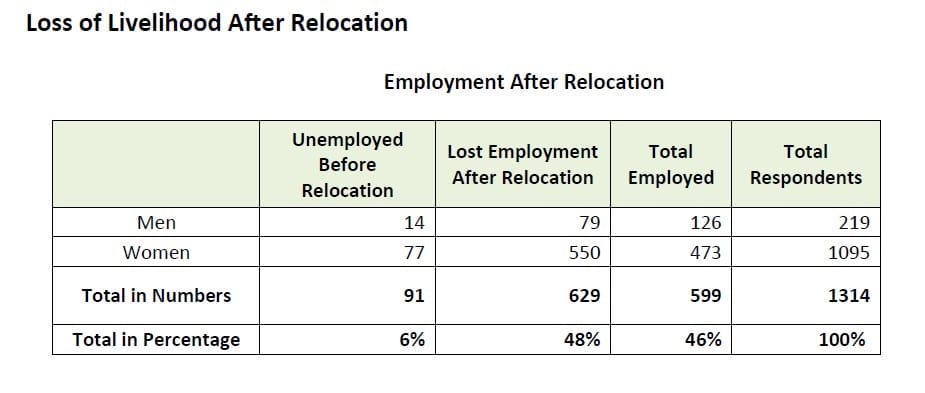

According to a study titled ‘Impact of Resettlement on Livelihoods of Families in Perumbakkam’, conducted by IRCDUC and Housing and Land Rights Network, 48 per cent of the respondents lost employment after relocation and were unemployed at the time of this survey.

The assessment also reveals that of the women who lost livelihoods after resettlement, 50.2 per cent worked as domestic helpers. Of the 458 domestic helpers, 276 lost their employment as a result of relocation. Women dependent on the Chintadripet Fish Market also lost their jobs: 26 of the 40 women involved in fish vending in the market lost work.

Adverse effects of eviction

Other issues add to their difficulties. Many women, who worked as domestic workers in their old areas before evictions had their workplaces at walkable distances. They did not have to spend their earnings on travel. Similarly, most men were able to find temporary jobs in the old areas as they were able to travel easily to seek employment.

However, after relocation to areas like Perumbakkam, Kannagi Nagar and Semmenchery, about 35 km away from the core areas of the city, both men and women are forced to spend a huge chunk of their earnings on commute. This makes women more dependent on men as they are neither able to find jobs in the vicinity, nor in their old areas.

“For a long time, Perumbakkam did not have adequate bus service. So, the men here got used to sitting idle. If they went out in search of jobs, they would spend Rs 200 (up and down) every day on travel. But there was no guarantee of securing a job, and often the men ended up losing Rs 200 and earning nothing. Had the government ensured proper public transport before resettling people, it would have helped the people. The lack of such pre-planning forced the men into alcoholism, while putting the burden of the family’s upkeep on the women’s shoulders,” says Nandhini from IRCDUC.

Pointing out how difficult it is for people from resettlement areas to find a job, Mercy says, “Employers do not trust people coming for work from resettlement areas. They brand us as ‘slum people’, ‘drug addicts’ and ‘thieves’. At one point we had to get a ‘conduct certificate’ from the police to go as domestic workers in the apartments near resettlement areas. We are from a good family and we are educated. But they treat us like criminals.”

The different faces of violence

Being without work, the men often hassle their wives in different ways. “We dress to work so we can gain the respect of our employers. This only draws suspicion from the male members of the family,” says a community worker.

“The husbands start questioning the wives, pick fights and abuse them (accounting for physical, verbal, sexual, and emotional abuse as per the definition). They ask other men to stalk their wives. This is a sign of how the way men think changes when they are jobless.”

Read more: Explainer: Steep rise in domestic violence complaints, but where are the protectors?

Malarkodi’s story is a case in point for economic violence. The sexagenarian used to run a makeshift fruit shop before being evicted. She had ownership over her money and the shop. The resettlement changed everything. As her husband couldn’t get work, he took over her shop and she became a homemaker.

“He just gives me Rs 20 a day. We have a whole cart of fruits and I am not allowed to eat even one of them. If I ask him for more money for other expenses, he drinks, beats me up, asks me to go begging and move out of the house,” she says.

At the age of 64, Malarkodi finds it hard to find any job. She puts up with her abusive husband as she has no other respite.

Here are some of the helplines in Chennai for women going through domestic abuse

- Women’s helpline – 181

- Women’s helpline – 1091

- Distress hotline of Chennai Police – 8300304207

- Union governments’ single emergency helpline – 112

- The Banyan – Emergency Care Whatsapp – 9840888882

- Nakshatra NGO – 9003058479 / 7845629339

- AWARE – 8122241688

- The International Foundation for Crime Prevention and Victim Care (PCVC) – 24*7 toll-free helpline by PCVC – 044-43111143, Whatsapp chat support – 9840888882

Like Malarkodi and Jency, many women who go through domestic violence do not come forward to seek help or register a complaint. This is one of the main challenges in handling the DV cases in resettlement areas, according to community workers, as physical abuse is normalised.

Often, when a woman files a DV case, it may end up in a separation or divorce. The woman has nowhere to go. The fear of being rendered homeless, prevents her from filing a DV case.

The anecdotal experiences shared by these women make the connection between loss of livelihood due to evictions and its impact on family life, leading to domestic violence. The women, who have been made vulnerable by lack of proper rehabilitation planning by the government, do not have a ‘safe place’ to go to when they decide to seek help.

We will continue to look into the grievance redressal aspects in the upcoming articles in this series.

(*name changed on request)

[The author thanks Nitika Francis, a journalism student, for her help with transcribing inputs from the Focus Group Discussion]