For better or worse, we are married to plastics, and plastics have permeated into our very being. What was once invisible, is suddenly all round us, in the form of waste and pollution. Simple everyday plastic products such as water bottles, plastic bags, toys, throw-away cutlery, fast fashion, food packaging, personal care products, all seemingly harmless, are all causing severe environmental problems, in the form of plastic pollution. From clogged storm water drains to beach litter, from dead rivers to air and soil pollution. Surgeries performed on animals to remove plastic from the bellies make it to the news regularly.

Plastic pollution is no longer a local problem, and world over, legislation and interventions to address the issue are on the rise. But addressing the issues of plastic pollution, through a singular lens of either waste management, marine litter or single-use plastics is not sufficient, as it further compounds the problem of effectively finding solutions.

What is required is a bold plan, a convergence, a commitment and a coming together of all the countries around the world to holistically deal with the issue that affects human health, biodiversity, environment and climate change.

State of plastic pollution in India

In December 2021, the issue of plastic pollution made headlines, with news of India’s plastic waste generation doubling in the last five years, with an average annual increase of 21.8 per cent. This was revealed in a reply from Bhupender Yadav, Union Environment Minister, to a question in the Lok Sabha on whether the Government was monitoring the quantity of plastic waste flowing into the sea.

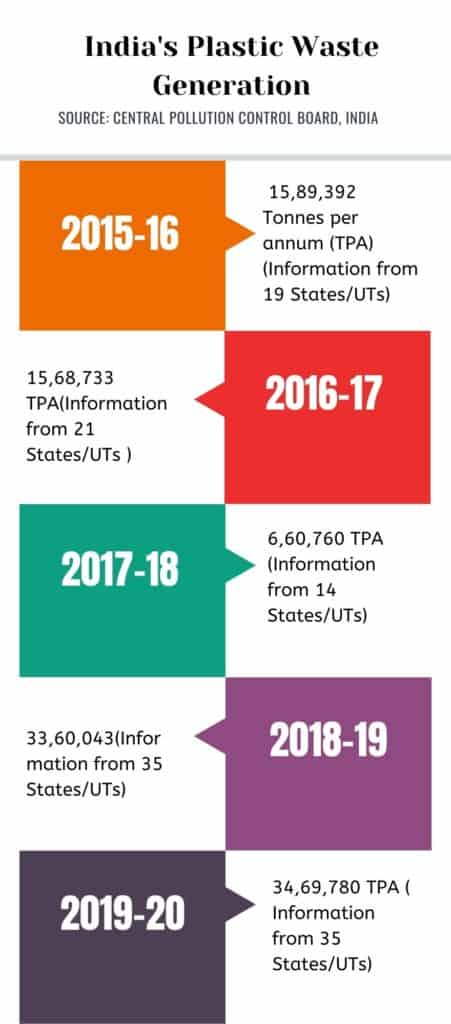

The Central Pollution Control Board’s (CPCB) annual reports also point to the increasing numbers: from 15, 89, 393 tonnes per annum in 2015-16 to 34, 69, 780 tonnes per annum in 2019-20, with the exception in 2016-17 where the recorded numbers state 15,68,733 TPA. The CPCB’s report observes that India is the fifth highest generator of plastic waste in the world. Of the ten most polluted rivers that contribute to plastic debris, three flows through India: the Ganga, Indus and Brahmaputra.

A 2016 study from National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (CSIR-NEERI), on municipal solid waste (MSW) components of 12 high-altitude cities in India, showed that the plastic composition of the garbage generated, calculated on weight basis, stood at 8.7%. According to Roshan Rai, Zero Waste Himalayas, “The Himalayan Cleanup since 2018 has consistently shown that there is not a patch in the Indian Himalayan Region free of plastic pollution. This is of great concern considering the importance and fragile socio-ecology of the Himalaya.”

Read more: How can India move towards more sustainable waste management in tourist cities?

A study in July 2018 by IIT Kharagpur surveyed drains in Delhi, and found that 22% of the silt in drains was gutkha and pan masala packets and 27 percent was plastic bags and plastic films. Interestingly, section 4(f) of the Plastic Waste Management Rules, states “Sachets using plastic materials shall not be used for storing,packing or selling gutkha, tobacco and pan masala”.

Given these alarming statistics, plastic waste will continue to pose a huge risk. While land based sources contribute to plastic marine debris in a big way, the problem of plastic waste is all pervasive, across ecosystems.

Legislative instruments

In 2016, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change ( MoEF&CC), released the Plastic Waste Management Rules 2016. The rules sought to address the issue of plastic waste, by phasing out multilayer plastic packaging, which currently cannot be recycled, within two years of the notification.

However in 2018, through an amendment, the clause read ‘Manufacture and use of multi-layered plastic which is non-recyclable or non-energy recoverable or with no alternate use of plastic (emphasis added) if any should be phased out in two years’ time’. This, in essence, identified certain problematic plastics (considered recyclable, energy-recoverable or having alternative use) and paved the way for their incineration/co-processing, instead of mandating product redesign or phasing out.

Fixation with single-use plastic since 2018

2018 was also notable, as the term ‘single use’ was voted the word of the year by Collins Dictionary. Single-use can be described as ‘made to be used only once’. In the same year, India hosted the World Environment Day and announced an ambitious plan to Beat Plastic Pollution, by eliminating all single use plastic in the country by 2022. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, called for a global movement to beat plastic pollution.

Soon enough, many states and cities in India, implemented single-use plastic bans, with varying priorities. Some have banned plastic bags and permit a certain thickness, while others have banned certain plastic items. Digital media campaigns around single-use plastics gained momentum with the Swachh Bharat Mission, which awarded points to states that have imposed the ban.

Before the pandemic, on the surface at least, it would have seemed that India was on track to dealing with the issue of single-use plastics with state governments taking the lead in penalising and fining citizens and vendors alike, but it all changed with the pandemic. Single-use plastic is on the rise, and enforcement of the ban has taken a back seat.

Read more: Two years since the ban, plastic is back in a big way. Is COVID the real reason?

In 2021, the government released the amended Plastic Waste Management Rules 2021 with the aim of phasing out certain single-use plastics. The government also released the draft EPR regulations, which fell short of addressing the plastic pollution problem.

Read more: Managing plastic packaging waste: Why the draft EPR rules are likely to fall short

India at the United Nations General Assembly

Parallely, India pursued its global vision to phase out single-use plastics at the 4th United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) in 2019. India sponsored a draft resolution, titled “Phasing Out Single-use Plastics” but was disappointed when the final resolution adopted turned out to be a watered down version, with the key phrase “phase out” being deleted.

The title of the resolution was changed to read, ‘Addressing single-use plastic products pollution’, and it called upon member states to develop and implement national / regional actions and pushed the deadline to reduce it to 2030.

India continues its advocacy around single use plastics and this year at the UNEA 5.2 and has proposed a new resolution titled ‘Framework for addressing plastic product pollution including single-use plastic product pollution’, which builds on the previous one sponsored by India. While acknowledging that one of the main sources of plastic pollution and marine litter originates from land-based sources, it raises an urgent concern over the increase in the use of single-use plastic products.

The new resolution

- Calls for international collaboration and cooperation

- Encourages multi stakeholder dialogue

- Recognises the need to adopt principles of waste hierarchy of reduce, reuse and recycle

- Stresses implementation of Extended Producer Responsibility

- Invites member states to prepare national or regional actions plans through policy and legal frameworks

- Underlines the need for financing and technology mechanisms

- Calls for voluntary data disclosure and monitoring

Presently, at UNEA 5.2, India’s resolution is being put in the cluster with two other resolutions. The first one was sponsored by Rwanda and Peru in September 2021, calling for an internationally legally binding instrument on plastic pollution. The second one is by Japan that calls for an international legally binding instrument on marine plastic pollution.

What India must do — domestically and internationally

At the national level, this year, the government has released the Plastic Waste Management Rules 2022 for public comments, which in essence contains similar provisions as the EPR regulations, and fails to holistically address the problem of plastic pollution.

At the international level, India’s standalone current proposed resolution is neither ambitious nor aggressive, and pales in comparison with the Rwanda Peru Resolution. By singularly focussing on the problem of single-use plastics, it limits its scope to comprehensively address the plastic pollution problem holistically.

Ahead of UNEA, India has just released the Plastic Waste Management (Amendment) Rules, 2022, with an aim to provide a roadmap for plastic packaging waste. Yet the new rules fall short of holistically including all stakeholders, including the entire recycling value chain that significantly contributes to retrieving plastic waste.

As Lakshmi Narayan, Co-founder of Swachh, Pune says, “Time and again, India fails to acknowledge, incorporate and legitimise the right people, shifts focus from problematic plastics and facilitates potentially undesirable end-of-life processes.” Instead, India must ponder over the following points, and

- Demand a globally binding treaty that addresses pollution from marine, terrestrial and freshwater environments, given the transboundary nature of the issue, using a lifecycle analysis approach targeting upstream( production), midstream(design) and downstream (waste management). Voluntary targets are problematic and lack seriousness to actively solve the problem.

- Amplify the need to recognise informal waste workers and mandate their inclusion in the waste management systems at the global level. This is a significant direction that India has already taken at the national level with the Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules 2016 and the Plastic Waste Management (PWM) Rules 2016, but it must now push for these to be included in the current framework and global treaty dialogues.

- Formulate an Integrated River, Marine and Ocean Litter Policy and a framework to address plastic waste in remote and mountainous areas at the state and central levels, together with both SWM and PWM Rules

- Launch National and State Action Plan under the PWM Rules as a long term, time-bound national level strategy to tackle the issue of plastic waste across the country in a comprehensive manner with targets to achieve by 2025, incorporating EPR targets as specified in the new PWM Rules Amended in 2022.

- Undertake comprehensive data management and monitoring across the city, and make data available in public domain.

- Take a tough stand on end of life disposal to address the issue of plastics. Lakshmi adds, “ India needs a comprehensive, holistic lifecycle approach, with a graded phase out starting with multi-material and single-use items that pose a waste management challenge, and a close evaluation of end-of-life processing technologies based on their health and environmental impacts, and implications for continued production of plastics. This can go a long way in setting the tone for a meaningful Plastics Treaty”.

- Ramp up behaviour change communications and implementation. As Myriam Shankar, founder, The Anonymous Indian Trust (TAICT), Bengaluru says “In my mind pollution has less to do with the material, but with human behaviour and proper implementation of SWM by the government”.