Thirty-year-old Raghu Kamble has been working as a garbage picker for high rises in Chembur, Tilak Nagar and surrounding areas for three years now.

For him, every morning is the same. He routinely visits the residential buildings at 9 AM — accompanied by nothing but a flimsy surgical mask for protection from the deadly virus looming over Mumbai city.

According to statistics released by Bhartiya Mazdoor Sangh, over 6,500 contract workers in sanitation have been working throughout the pandemic without safety gear like Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) or hazard pay.

By mid-May, Maharashtra had seen no less than 30,000 new COVID cases being reported every day. The capital city of the state had accounted for a majority of rising cases, but since the city has moved into lockdown, mortality and infections notably reduced. As of June 9, Mumbai has recorded 785 fresh cases, adding to the city-wide caseload of 17,939 active cases.

COVID19 hotspots

The financial capital’s M-Ward, which was declared a hotspot in April, has also registered a sharp fall in COVID19 infections. The M-Ward is home to Chembur which is Raghu’s place of work. According to M-Ward’s Medical Health Officer, Bhupendra Patil — the ward has some of the strictest rules when it comes to quarantining and COVID-related precautions.

As police sirens blare in the background and people scram towards their homes in Chembur, Raghu and his peers continue their quotidian drudgery.

Although he has not tested positive even once, he fears for his life these days. “Neither the government nor seth (owner) has done anything for us. We are not allowed to form unions, either.”

For a state that boasts a rich history of trade and worker unions, Kamble and his coleageus are systematically excluded from unionising. It is a symptom of how recent corporatisation has eschewed pro-worker politics in Maharashtra.

Read more: Children in under privileged communities face increased pandemic-induced anxieties

The trash Kamble collects every day is rife with bodily fluids, contaminated bio-medical waste and hazardous materials which may be likely carriers of the fatal virus. In case of symptomatic patients quarantined at home or asymptomatic persons unidentified for infection — the chances of workers like Kamble coming in contact with infected materials and surfaces are magnified. Seen working without gloves, PPE kits or practising hand hygiene — they present the risk of spreading infections rapidly.

Kamble earns a meagre ₹260 daily — putting him below the stipulated minimum wages for unskilled workers in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. “I have only studied till sixth standard. This is the only job I could get,” Kamble says. “If I happen to land something better, I will definitely leave this job,” he adds.

He shuffles uncomfortably when asked if he has faced caste-based discrimination but ultimately denies any such incident.

Minimum wages

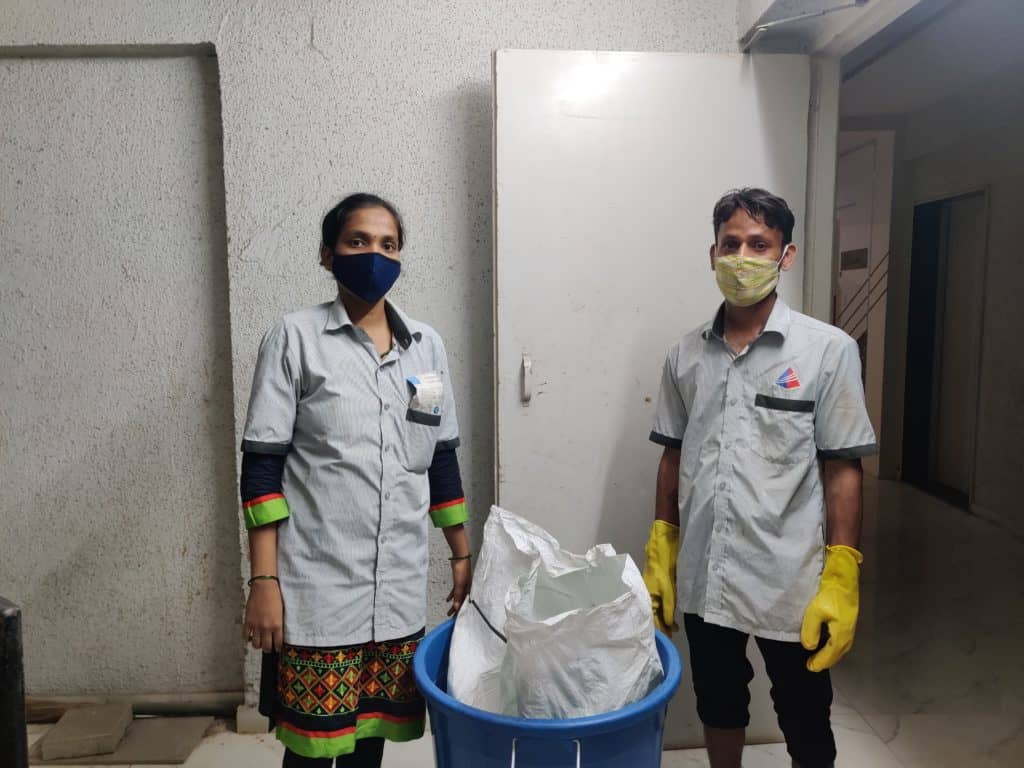

While Raghu hopes to get married after Diwali once he can visit his village in Solapur, young married couple Suman and Anil are burdened with feeding three children with their minimum wages.

Every day at 7 AM, the couple leaves their chawl in Mankhurd to collect garbage from each flat in the Tilak Nagar area. Anil drags a garbage bin from door to door and Suman, who works without gloves, gathers waste from households in high rises and comfortable apartments. Calling such workers ‘housekeeping’ staff by managers and residents is nothing more than an elitist cover-up.

Even with the city limping towards normalcy, access to vaccination is a privilege. Despite sustained exposure to hazardous and potentially COVID19 infected waste, sanitation workers and garbage pickers have not been qualified as frontline workers by the Maharashtra government.

Despite putting their lives on the line every day, be it rain or shine, Suman says sanitation workers like her are hardly respected like other frontline workers. “Kya kare, pet ke kiye karna padta hai (We don’t have an option but to work like this),” she says. “If we test positive for the virus, we might end up passing it on to our three children, or our neighbours in the chawl,” says Suman.

Physical distancing a luxury

For the couple, physical distancing is a luxury. As of April 2020, over half of COVID19 casualties in Mumbai have arisen from Mumbai’s slums and chawls. Chawls, like the one Suman and Anil live in, are congested pockets of the city, deemed tough-to-manage by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC).

With every kholi packed with family members, physical distancing is impossible for the residents of Mumbai’s crowded chawls. Mankhurd’s chawls are populated with ‘lower-caste’ individuals, most of whom are blue-collar workers from low-income groups. Many of chawl’s residents have lost their livelihoods in this pandemic, rendering them unable to afford basic medication, sanitisers, masks and ration.

The way forward is to encourage increased testing, contact tracing, walk-in vaccination for persons without access to the internet and declaring hygiene and sanitation workers as frontline workers with guaranteed wages and comprehensive protection.

Recently turned 18, Akbar, too, is one of the safai karamcharis. Akbar’s previous contract ended abruptly two months ago. As the only breadwinner in the family, his job hunt landed him another contract as a garbage picker in Eastern Chembur and Western Kurla.

Along with twenty-year-old Vishal, 18-year-old Akbar now works every morning with the hope that this contract is not over before he knows it. He eats chips as he answers: “Pure contract ka ₹8000 milta hai (I am paid ₹8000 for the entire contract.)” The contract is not monthly — sometimes it may extend up to one and a half months or more. When asked if he is married or not, he hides his face behind the packet of chips and nods his head. “If I ever have children, I will make sure they study and become what I couldn’t,” young Akbar confides.

Also read: