In 2006, Pune became the second city after Ahmedabad to introduce the BRTS (Bus Rapid Transit System) project, an ambitious scheme that envisaged the implementation of a high-quality public transport system to offset the rising vehicular traffic and the subsequent congestion within city limits.

To provide its citizens with a reliable medium of public transport, the scheme promised the construction and layout of dedicated bus corridors along with new air-conditioned buses and high-end terminals and stations.

In its pilot phase, the project partly operationalised a high capacity bus system on two corridors, the Swargate–Hadapsar (East‐West) Corridor of 10.2 km, and the Swargate–Katraj (North‐South) Corridor of 5.8 km. This involved the widening of roads and the layout of municipal services such as water supply and electricity along the routes covered.

Compared to the regular bus service, the Pilot BRT successfully marked an increase in number of passengers on the bus routes, along with increased frequency of buses and an overall efficiency in fuel consumption and driving conditions. However, much to the dismay of commuters, the project soon began facing major roadblocks in the initial phase itself.

“The pilot BRT project looked like a dream project which would improve commuting experience for the passenger,” said Jugal Rathi, a city-based activist. “Yet, till date, nothing much has happened. There is no end-to-end corridor dedicated for BRT and the power supply is shut at many times on BRT routes”.

Since its launch, the project, operated by the Pune Mahanagar Parivahan Mahamandal Limited (PMPML), has received over Rs 1,013.97 crore from the Centre under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM). The Pune Municipal Corporation has spent another Rs 100 crore from its own budget to improve the BRTS mechanism. However, despite the large budgets and a lapse of over 12 years, the project is yet to really take off.

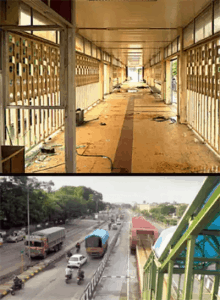

“It is sad that despite getting a grant, PMC has not been able to execute this project effectively,” added Jugal Rathi. “BRTS is a good concept, but the condition of the existing BRTS corridor is very poor and shabby. We as civic activists suggested various measures, but the administration did not want to execute it.”

Where does the project currently stand?

The original plan envisaged the setting up of over 112 km of BRTS routes criss-crossing the city. But as of today, only a few corridors, namely those covering Yerawada—Wagholi (8km), Sangamwadi—Vishrantwadi (8km), Sangvi Phata—Kiwali (14 km), Kalewadi Phata—Dehu Alandi Road (11 km), Nigadi—Dapodi (12 km) and Nashik Phata—Wakad (8 km) have become operational. While 23 additional roads have been proposed, only a handful have been built.

Even the corridors built during the pilot phase now need repairs. For instance, the Katraj to Swargate stretch is currently un-operational in places as the work of building bus stations along the route is only half-done. Similarly, the automatic doors (which detect incoming buses and open in line with them) on Ahmednagar road and Alandi road BRTS routes have been dysfunctional for months.

Commenting on this, activist Qaneez Sukhrani said: “The automatic doors at the stations are always open. Water accumulates around the terminal during rainy season, there are no toilets and the lighting is poor making it unsafe during nights.” Throwing light on the equally miserable situation of the Phase 1 Corridors, Qaneez added that the “state of BRTS Phase 1 Nagar Road- Sangamwadi- Vishrantwadi corridor is dismal to say the least. The civic body now wants to add 68 km to the routes without correcting the earlier faults”.

The PMPML has cited shortage of buses as a major hurdle in bringing the project up to speed. Only 1100 buses are operational on the BRTS corridors, whereas the PMPML said it requires close to 3450 buses to make the project a success. “Our biggest issue is the number of buses,” said Ajay Charthankar, PMPML joint managing director. “Presently PMPML has 1292 buses and an additional 678 buses from private contractors. Out of the 1292 buses, only 1100 buses are on road on any given day. Many buses are old and continuously need maintenance, which is proving to be costly for PMPML.”

|

Some Commuter Statistics for 2018

|

Do delays in BRTS implementation signal failure?

While the BRTS is designed to provide an integrated network of safer, faster, affordable and more efficient public transportation, the project is plagued by major execution and operational challenges. Project milestones have not been met or are poorly implemented.

An in-depth analysis of this by IIT-Bombay in January 2014 revealed flawed design, poor implementation, and the near absence of a centralized BRTS cell as some of the biggest hurdles in the project’s successful implementation. Some of the other points highlighted by experts include:

Advisory Non-Compliance: According to the National Urban Transport Policy (NUTP) 2006, construction of continuous bus-ways, encroachment-free footpaths and cycle tracks were imperative to maximize the speed and efficiency on the BRTS routes. This was also a pre-condition for receiving central funding. However, the project has shown severe non-compliance on these parameters with most routes lacking basic safety infrastructure.

Accidents and Fatalities on the BRTS Corridors: Since its launch, the BRTS corridors have witnessed several accidents owing to lack of proper signals and poor monitoring by the traffic police. The bus lanes are regularly used by pedestrians and private vehicles, some of whom enter the lanes inadvertently. To tackle this problem, it was suggested that the entry and exit points of the BRT lanes be fitted with sensor-activated electronic gates that would allow only BRT buses, fitted with chips, to pass through. But PMPML is yet to act on this.

A two wheeler encroaches the BRTS lane. Such and other violations lead to accidents. Pic: Ekta Joshi

Infrastructural hazards: As mentioned above, the automatic doors and digital displays are not working at many bus stations. This makes travellers lean out to check on the arrival of the next bus. Also, the width and number of intersections on the BRTS routes need to be reduced. They are currently too wide and allow only 45-degree right turns instead of 90-degree right turns, which causes congestion and accidents. Moreover, the lanes and railings are not well-aligned on most corridors with damaged bollards further increasing the risk of fatalities.

Commenting on the fatalities on BRTS corridors, Vivek Velankar, Founder of Sajak Nagrik Manch, a non-governmental organisation said: “Automated doors of the bus shelters have not been repaired which could result in a fatal accident as commuters lean out to look out for approaching bus as electronic boards are not functional. CCTVs are also not installed at every traffic junction to allow traffic police to capture violations.”

“We had urged the civic body to prepare a detailed project report,” added Maj Gen S C N Jatar (retd) of Nagrik Chetana Manch. “There is no BRTS in Pune. The civic body should return the funds it received under the JNNURM to the state and central governments”.

Should the PMPML pull the plug on BRTS project?

Given the rise in accidents and the heavy operational costs, the BRTS system has now become a liability. Elaborating upon this, traffic transportation expert P G Patankar said: “How can Bus Rapid Transit apply to a congested city like Pune? If it has worked in South America it is because the density of population is lower compared to our cities, and roads there are as wide as our expressways, so you can have dedicated bus lanes without disrupting other traffic. It would be better to increase the efficiency and frequency of the present PMT fleet. That would not require a dedicated lane, a luxury for our congested cities. What we require is point-to-point buses at higher frequencies. The BRTS experiment is sure to fail.”

While crores have been spent in the ambitious BRTS scheme, citizens have gained little. Many like Patankar have zero hope that the BRTS project will ever be completed successfully. But Puneites, especially those relying on public transport for their daily commute, continue to hope for its success. Most say it is possible for the PMPML to plug the loopholes in the planning and execution of the BRTS by taking a few basic steps like:

Introduction of a dedicated BRT cell: The project requires a dedicated cell to ensure timely implementation and to tackle operational and other issues that it currently faces, like ensuring additional buses during peak hours. There is also a need to introduce uniformed ticket checkers at the bus stops. This needs to be supported with regular training and inculcation of a more professional attitude amongst the BRTS staff and workers. “There is presently no body accountable for the shortcomings of BRT,” pointed out Qaneez Sukhrani. “A BRT cell is essential and needs to be set up.”

Optimising patterns and increasing frequency: It has been pointed out that the frequency of buses on the BRTS routes does not correlate with the number of commuters in those areas. This requires mapping the most popular routes with an increased frequency of buses.

Pranjali Deshpande, a city-based activist, in her presentation on a survey conducted by the Institute of Transport and Development Policy on passenger reactions about BRT in Pune and Pimpri-Chinchwad said: “The survey pointed out that usage of BRT by commuters was up just 12-17 per cent, with many complaining of less frequency of buses as a major issue”.

The survey added that “the number of personal motor vehicles on the road has been growing unabated due to infrequency of buses. Considered a first for any urban area in India, Pune’s total number of vehicles has surpassed the human population.”

Infrastructural Safety: As noted in a Case Study of Pune BRTS in the International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology (IJRET), safety on BRTS routes and at private vehicle crossings needs to be prioritised and monitored effectively. This requires alert traffic policing, adequate lighting, signboards and blinking lights to be installed at commuters’ crossings.

If, how and when all this would happen, though, is for the PMPML and the government to answer.

LET ONLY TWO WHEELERS USE THE brts LANE. If brts is used exclusively for 2 wheelers, it would at least keep the two wheeler riders free from getting brushed by mighty buses and cars. This is the only way to regulate the traffic

It’s an excellent project and would suggest our honourable cm and honourable road and transportation minister to use it once from any of the public junctions (bus stand, railway station or airport), I bet you will never forget this journey for lifetime.

Don’t improve this peice of shit proj due to this brt there is hardly any space on road for other commuters. And please write a article on traffic jams in pune it takes 2 to 3 hr for 45 min journey. Due to this traffic jams I am changing my job and moving to another city so much frustrated cause of traffic

I am surprised that there is no mention of the Dapodi Nigdi route which was amongst the first to be built, but not operated since more than 10 years. It is unnecessarily occupying space restricting traffic. Already there is need of repair. Who is responsible for such bad planning?

I feel that it should be used for two wheelers because they are just not following traffic rules.

In the first place why did they not make this provision on the side instead of the middle of the road occuping so much place with no space left for other commuters.

To implement BRT like projects you first need to understand the type of commuters in a city. Here most of the people travel by bikes and cars. So first Lets understand the frequency of the buses in any area and occupancy in those buses. Then we can think of applying BRT like projects. I said “think of”. Pune needs wide road now. we do have unutilized BRT roads, why can’t we use that for widening the roads?