Tayappa Dhangar, who is 41 and lives in Andheri, needs heart valve replacement surgery. He works as waste picker and is eligible for the indigent patient scheme under a charitable trust hospital. However, a well-known charitable trust hospital in South Mumbai has refused to perform the surgery free of cost.

The hospital provided a surgery cost estimate of around Rs 15 lakh, with assistance limited to only two lakh rupees. Tayappa, who earns a daily wage of Rs 300, does not know how to gather the remaining Rs 13 lakh for the surgery.

Tayappa’s situation is not unique. Many individuals in Mumbai face challenges in accessing treatment under Bombay Public Trust (BPT) Act schemes.

What is the Bombay Public Trust Act scheme?

The Charitable Trusts registered under the Bombay Public Trusts Act, 1950 (B.P.T. Act) that operate charitable hospitals, including nursing homes or maternity homes, are mandated to allocate two per cent of their income to the ‘Indigent Patient Fund (IPF). For this they receive government subsidies and concessions on land, electricity, building rules, income tax and import of medical equipment. In return, they are expected to provide free and subsidised medical care to economically weaker sections.

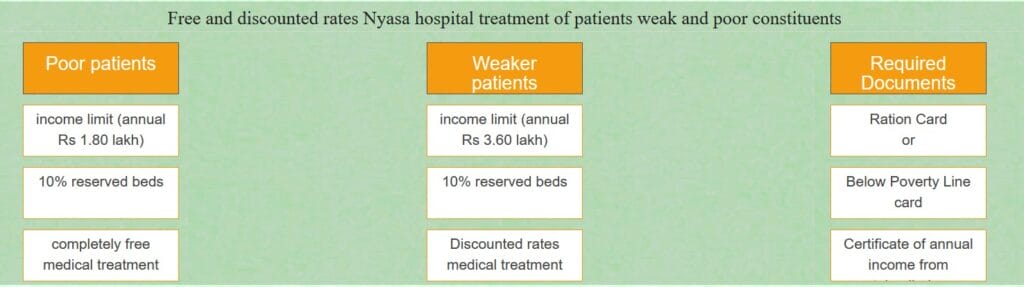

As per the act’s provisions, these hospitals are obliged to set aside and designate 10% of their total operational beds for indigent patients, providing them with free medical treatment using the IPF Fund. Additionally, they are required to reserve and allocate 10% of operational beds at concessional rates for weaker section patients under the same fund.

This scheme was launched on September 1, 2006, following the directives of the Bombay High Court. In this scheme, individuals with an annual income of up to Rs 1.8 lakh are eligible as indigent patients, while those with an annual income of up to Rs. 3.6 lakh qualify under the weaker section category.

Time consuming procedures

Patients or their relatives are required to submit an application for admission under this scheme, along with the necessary medical history. Only after the hospital committee reviews and approves the application, the patient gets admitted under this scheme. This process takes nearly a month, requiring consistent follow-up with the hospital.

“If you have direct contact with hospitals or political figures, your application will be approved within eight days,” mentioned a relative of a patient while sharing their experience of receiving treatment under this scheme.

A social worker at a charitable trust hospital in South Mumbai mentioned that they receive numerous applications for admission under the BPT Act scheme, and the hospital has many patients on the waiting list.

However, when Citizen Matters visited the hospital, the reporter found that the notice board at the hospital indicated availability of 10 beds for indigent patients and 13 beds for the weaker section. This raises the question: If there is a waiting list for admission under the scheme, why are these beds vacant?

Read more: Mapping Mumbai’s hospitals

Struggles faced by patients and their relatives

The primary obstacle is acute lack of awareness and guidance for patients and their relatives regarding the BPT Act.

Many poor people residing in Mumbai have not heard about this scheme. Patients or their relatives are unaware of the presence of social workers in the hospitals, who can guide them for financial assistance. Unfortunately, even doctors and other medical staff often fail to direct them to meet with social workers for admission under the scheme.

In cases where a patient from the weaker or indigent section requires emergency medical treatment, there is no dedicated desk to provide information about the entitled BPT Act scheme.

“With the exception of a few hospitals, most of them are not actively motivated to offer medical treatment under the BPT Act Scheme,” said social worker Nirajan Aher, associated with Alert Citizen Forum Group.

Pic: Shailaja Tiwale

Niranjan further noted that social workers within charitable hospitals are often reluctant to provide comprehensive information about the scheme to patients or their relatives. Consequently, relatives frequently find themselves without proper guidance, opting instead to transfer the patient to a public hospital or resorting to borrowing money to pay for treatment.

Vinod Shende, representing Sathi NGO, mentioned that charitable hospitals frequently demand unnecessary documents from patients’ relatives, causing stress.

“Some hospitals are unclear about the required documentation, resulting in the misleading the patient’s relatives. For example, the hospital informs patients that they require an income certificate of up to Rs 2 lakh for free treatment under the indigent scheme, whereas the actual upper limit for indigent patients is Rs 1.8 lakh,” he said.

Niranjan says they receive complaints from numerous patients that hospitals refuse admission under this scheme, citing the exhaustion of the IPF fund. He says there is no transparency or any system through which the citizens can verify how the hospital utilises the IPF fund.

Rajendra Dhage, associated with Vasai Rugn Mitra organisation, said with the revised annual income criteria, the upper limit for the weaker section has been increased to Rs. 3.6 lakh. However, families with an annual income exceeding Rs one lakh get a white-coloured ration card, indicating they are not from the poor/weaker section of the society. Many hospitals deny treatment to patients under the weaker section (essentially those whose annual income is between Rs 1 lakh and Rs 3.6 lakh) because they do not have a yellow or orange ration card.

These changes have not yet been implemented in the scheme’s rules and cause a lot of problems for the patients, explains Rajendra.

Poor monitoring of hospitals

The monitoring committee does not evaluate the utilisation of the IPF Fund or assess the rates charged by trust hospitals for the weaker section regularly.

The Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG)(2017) report says that the management of the IPF by hospitals is lacking. Either no IPF has been created, or if it is created, it accounts for less than 2% of the total patient billing. A sample survey by the state health department indicated that Jaslok, Breach Candy and Bombay hospitals used only 4% to 4.5% out of the mandated 10% beds to treat the poor.

Information furnished by the charity commissioner after inspection of 78 hospitals in Mumbai, conducted during 2009–14, revealed that more than 59% of the hospitals were not inspected for more than a year (CAG 2016). Further, no penalties were levied on the offending hospitals, even though the charity commissioner can direct the government to withdraw their concessions/benefits. There has not been a single instance of disciplinary action by the charity commissioner against any offending hospital.

Charity Commissioner Mahendra Mahajan said, there is no system to connect patients directly to the charity commission. “Most of the time patients come to the charity commission, when the hospital denies bed or charges extra bills. The monitoring committee has to address such complaints.”

Mahajan added that he urged the government to appoint a government social worker to ensure effective implementation of the scheme and utilisation of IPF Fund.

| Changes recommended in the BPT Act |

| The article titled ‘In the Name of Charity’ published by the Sathi Cehat organisation in Economic and Political Weekly makes following recommendations for effective implementation of the BPT Act scheme. * The IPF of each trust hospital should be made available online to bring transparency to the scheme. * The old scheme needs to be reevaluated. There should be an assessment of the subsidies and concessions, turnover of the hospitals for the last few years, number of patients treated for free and at subsidised costs. * Based on all this the “measurable charity” should be revised. The contribution towards IPF could be proportionate with subsidies, exemptions and profit earned by the hospitals, hence it may vary in different hospitals. * Inclusion of civil society organisations in the hospital committee to represent citizens and patients. * A dedicated helpline for the BPT Act scheme to assist patients and their relatives. |

Implementation of an online system

In Mumbai and the suburban area, 83 hospitals come under the Bombay Public Trust Act scheme, including Bhatia Hospital, Jaslok Hospital, Nanavati Hospital, Lilavati Hospital.

After receiving numerous complaints regarding a lack of transparency in the allocation of beds for indigent and weaker sections, the Directorate of Medical Education and Research (DMER) department established a committee to implement an online system for bed allocation under this scheme under the chairmanship of the Principal Secretary of Law and Judiciary Department.

The committee will recommend creating a specialised help desk at the state level to aid citizens in securing beds under this scheme in charitable trust hospitals. Additionally, the Law and Judiciary Department has issued a government resolution to establish special help desks at both state and district levels. These help desks will guide patients and their relatives.

A representative from the state health department mentioned that a committee is currently working on developing an online system accessible through both websites and mobile platforms. This system will be open to citizens and will oversee the allocation of reserved beds under the BPT Act at the district level.

The improvements to the scheme and its implementation may well be underway, but in the meanwhile, Tayappa continues to grapple to organise funds needed for his heart surgery. He, much like many others, remains uncertain about his ability to gather the money and ensure the required medical treatment.

| Essential Information for Accessing Charitable Trust Hospital Treatment |

| The Charitable Hospitals shall provide following non billable services free to the indigent patients as well as weaker section patients – (a) Bed (b) RMO Services (c) Nursing Care (d) Food (if provided by the hospital) (e) Linen (f) Water (g) Electricity and (h) Routine Diagnostics as required for treatment of general specialities (I) Housekeeping Services. In case of weaker section patients, the Charitable Hospitals shall provide medical examination and treatment in its each department at concessional rates. The weaker section patient’s bill of billable services shall be prepared at the rates applicable to the lowest class of the respective hospital. The medicines, consumables and implants are to be charged at the purchase price to the hospital, however the weaker section patients shall pay at least 50% of the bills of medicines, consumables and implants. If Doctors forego their charges, then the same shall not be included in the final bill of the weaker section patients. |

| Documents Required – The Charitable hospitals shall verify the economic status of the patients from their Medical Social Worker on the basis any one of the following documents: (i) Certificate from Tahasildar, (ii) Ration Card/Below Poverty Line Card |

| The Charitable Commissioner’s office is located in Worli, Mumbai. If a charitable hospital denies treatment under the BPT Act scheme or charges fees exceeding the regulated rates, patients or their relatives can submit their complaints at the Mumbai Inspector’s office located on the same premises. |

My name is Vinayak Shivagan. When I brought my father (Anant Shivgan) to Mumbai on Tuesday night from Rajapur village for ARDS in Lunge infection, I first took him to Cooper Hospital in Mumbai but as I did not have a bed there, I was sent to Sion Hospital. I took him to somaya hospital Trust Everadnagar Sion where I admitted him. No I asked my father to be treated under Mahatma Phule Yojana. But at that time they said to pay Rs 20000 first and then start the treatment. Then next morning I applied for Mahatma Phule Yojana but I haven’t got any reply from them yet and now the hospital is demanding Rs 1,50,000 from me. My father is in ICU since 7 days. Can anyone help me please? .

Yours sincerely,

Vinayak Shivagan