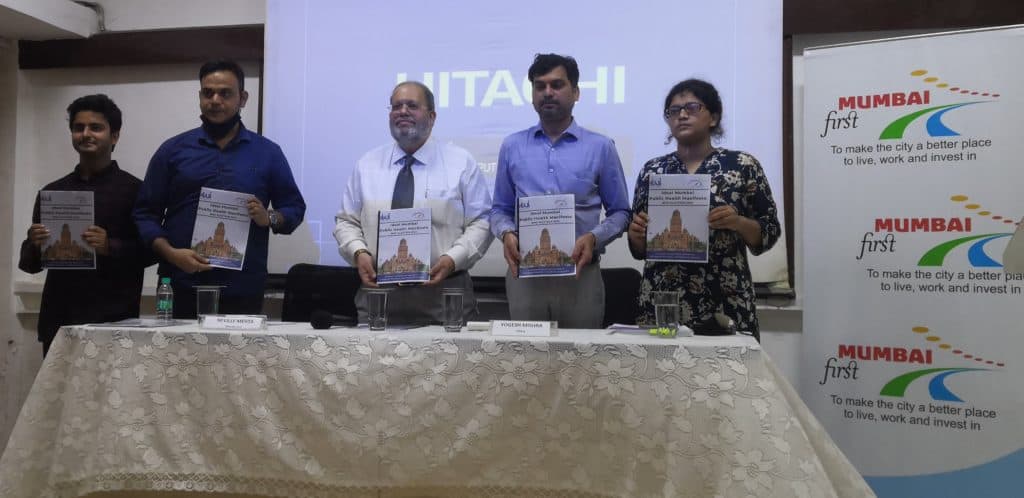

It has never been easier for political parties to know what their cities need. On December 22nd, the NGOs Praja Foundation and Mumbai First released the ‘Ideal Public Health Manifesto’. Handpicking 10 areas of priority within the BMC’s public health department, the manifesto is making a case for reforms that could mean better healthcare for all.

Elections for the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) are expected to be held in February 2022, and the city awaits an influx of manifestos where health will compete with concerns of road, water, and environment, among others. Instead of the freebies political parties usually offer, the NGOs have prepared this ideal manifesto that can be used as a ‘building block’.

It builds on the ‘Report on the State of Health in Mumbai’ published annually since 2012 by Praja, an organisation working towards accountable governance. Using information from RTI responses, the report is a comprehensive ward-wise analysis of public health services and schemes in Mumbai. Adding to this base of information is Mumbai First, a policy-influencing think tank. A round of consultations was also held with 18 other healthcare-related organisations, including Apnalaya, Asaar, Child Help Foundation, and Samaritans Mumbai.

“We would like to urge all political parties [..] to put investing in people’s mental and physical health and general wellbeing at the heart of their [public health] agenda…”

Opening text in The Ideal Health Manifesto

Budgeting for public health

The BMC’s public health allocation for 2021-22 is Rs. 4729 crores, 12% of the total budget. Historical trends, however, show that roughly 20% of allocations are left unutilised. In a bid to change this, the first point in the manifesto calls for the shifting of the budget to an outcome-based budget.

The point is mirrored in Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) Mumbai’s vision document, for its first foray in the city, following the implementation of a similar approach in Delhi since 2017-8. “Quarterly feedback is taken comparing the outcomes and output that were desired, and those that were achieved,” says Ratnabh Mukerjei, a policy researcher for AAP Mumbai. “This creates a monitoring system to ensure the budget is actually being used, and being used where it’s required the most.”

This could entail targets of the numbers of clinics built and patients treated. But, not all experts are comfortable with this approach. According to Dr Mathew George, professor at the Centre for Public Health at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, this is a slippery slope to commercialisation. “We found that when you pay doctors by the number of patients, they consciously keep aside severe cases that take time. This can create cases which need long-term care left behind as it is not lucrative – a kind of cream-skimming in health care.”

A pay-per-patient policy is already in place in some pockets of the private sector, such as private practices and consultants who are paid a ‘share’ of the patient’s fee. Unethical practices like unnecessary testing and cut-practice, in which doctors give and ask for referrals for a fee, are a pervasive side-effect of this.

Primary health care

Dr Mathew recommends an alternative facility-based framework for the budget, decided by the population’s size and morbidity load. Around 55% is the recommended share of primary healthcare, 30% for secondary, and the remaining 15% towards tertiary centres. Currently, only 20% of the health budget is diverted towards primary and preventive level care, consisting of municipal dispensaries, maternity homes, and health posts.

“Every 3 lakh people should be treated as a unit, and have one area hospital for secondary care. Below that, there should be one Urban Primary Health Center (UPHC) for every 50,000 people,” he says.

This coincides with a major point in the manifesto: to make the local dispensary the point of access for primary care. At present, there are too few – 199 – for that possibility. Mumbai requires 858, based on the National Building Code (NBC) norm (one for every 15,000 population).

Party promises vs reality

The number of dispensaries has only grown by 24 in the last term. The Shiv Sena corporator Abhishek Ghosalkar got his constituency in the R North Ward its first dispensary in 2020. A second dispensary, in the Ganpat Patil Nagar slum, is awaiting approval. He explains that allocations are made in keeping with public demand and land use plan in the masterplan – Mumbai Development Plan 2034.

The typical focus in manifestos tends to be on hospitals, either on constructing new, renovating or modernising them. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s 2017 manifesto promised new hospitals or centres within them for cancer, infectious diseases, trauma care, dialysis, AIDS, and Yoga.

Dispensaries found a mention in the manifestos of the Shiv Sena and INC, with the promise of an ‘at your door’ service.

Ratnabh says AAP’s plan is to construct mohalla clinics, which will “offer free, diagnostic tests, medicines, and quality health services, to enable a robust and accessible primary healthcare for all Mumbaikars.” An official of the Congress party said they were still in conversation with Praja Foundation for the public health initiatives in their manifesto.

Praja has also continuously highlighted the limited time availability of most dispensaries in their annual health reports. The overwhelming majority are open from 9 am to 4 pm, making them inaccessible to the working population. The only attempt to appeal to them was with a special outpatient ward for poor patients, from 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM, in the BJP’s manifesto.

“Having a facility doesn’t necessarily mean anything. The question is what kind of services they offer. Most of the UPHCs render only National Health Programmes with little or no curative care. It is time to equip UPHCs to provide full-fledged primary-level curative care,” says Dr. Mathew. “If that isn’t provided, the cases overburden the higher levels, which is what we’re facing at KEM Hospital.”

Read more: Why you should care about BMC elections

Health services audit

To spot these gaps, the ideal manifesto recommends a 3rd party audit of the BMC’s public health services. Dr Mathew agrees but contends a community-based monitoring system be integrated. “Every UPHC should list the services they provide, along with rates. In case of non-provision, citizens should have the power to question and report it to the concerned authority with a phone call.”

Data is an important focus of the Praja document, necessary for “monitoring the status of health as well as the progress of implementation for various schemes in Mumbai.” It demands that health data be generated, compiled, decentralized, and analysed on a real-time basis. The system is currently riddled with holes, the novel coronavirus being the exception.

Data on diseases, for instance, is only available from public health facilities. But even then, according to Dr Mathew, “The medical records are always incomplete. In public hospitals, this is often to do with the load they’re dealing with.” Private health facilities are compelled only to reveal cases of notified diseases, a set of typically infectious diseases compiled by the government.

Administrative problems with the Civil Registration System (CRS) for births and deaths have resulted in a backlog of years of ‘Cause of Death’ data. Praja has repeatedly highlighted the 12% increase in unexplained deaths – not attributed to COVID-19 – in 2020.

But the preoccupation with data comes secondary for Dr Mathew. “Without addressing the gross inadequacy in the system, whatever changes in technology or information cannot reap the desired benefits,” he says.

A holistic approach for health

The remainder of the manifesto is concerned with the prevalence and prevention of different diseases across the communicable and non-communicable (NCD), with particular attention to maternal and child health. The Sustainable Development Goals of eradicating tuberculosis, HIV, malaria, dengue, and all epidemics by 2030 have a long way to go. The maternal mortality rate is double the target of 70 deaths per 1000 live births.

NCDs such as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease are best tackled by prevention, early detection, and healthy lifestyle choices. The manifesto also recommends implementing schemes for cancerous and respiratory diseases, which accounted for 18,220 deaths in 2019.

Mental health, palliative, and geriatric care should be tackled by creating awareness, helplines, and the inclusion of community-level organizations, according to the manifesto. The 63% decline in people seeking medical help for mental health after the introduction of the Mental Health Care Act in 2017 calls for data to understand the scale of the problem.

Finally, health literacy quizzes, promotion of yoga, open spaces, and compassion and sensitization campaigns are recommended to ensure citizens’ continuous well-being.

Key points from the Ideal Public Health Manifesto:

- Regulation of the private sector

- Statistics team should regularly upload relevant data on the top 10 causes of death

- Do away with duplicity of schemes, as seen with malaria in Mumbai (Urban Malaria Scheme and National Vector Borne Disease Control Program)

- Target each non-communicable disease (NCD) specifically with its underlying causes and determinants

- Promotion of male contraceptive methods, which are much safer and easier to use

- Improve overall immunization rate to reduce preventable diseases, like tuberculosis and diarrhoea

- Incorporate micro-nutrients, like iron-rich food for tackling anaemia, in the overall food security policies and mid-day meal scheme