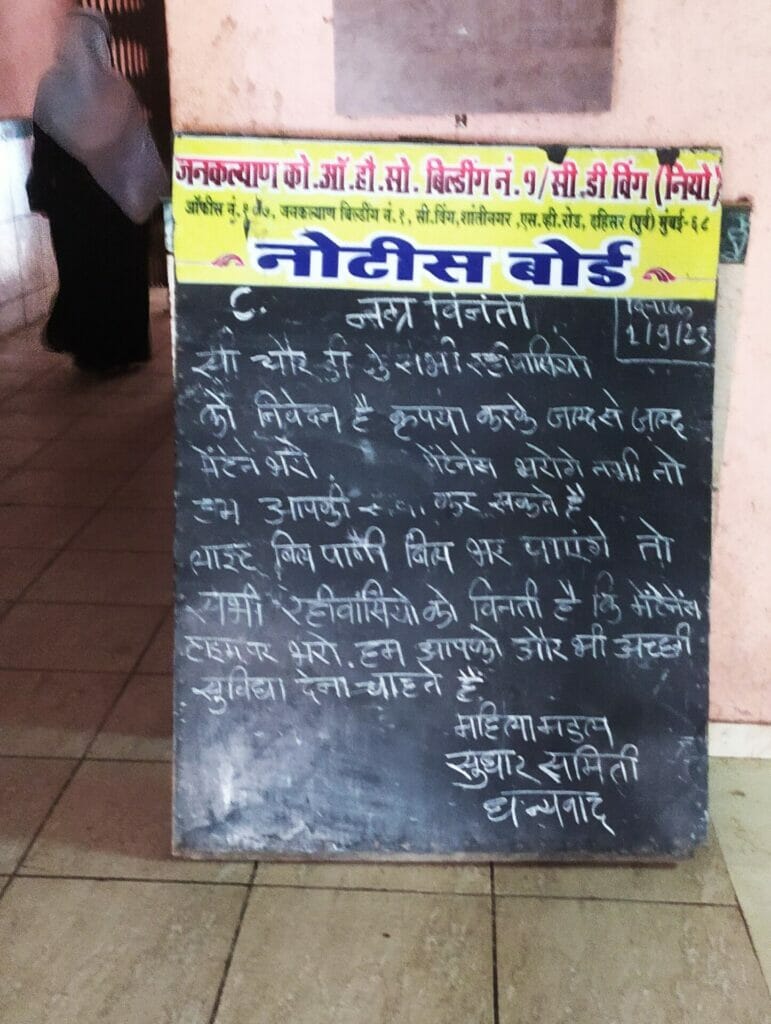

At the entrance of the Jankalyan Society at Dahisar, near the lift, a blackboard asks residents to clear their pending maintenance charges. Signed by the building’s Mahila Mandal Sudhar Samiti (MMSS) or resident women’s group, the note also urges residents that they would be able to offer better services to residents if maintenance dues are paid on time.

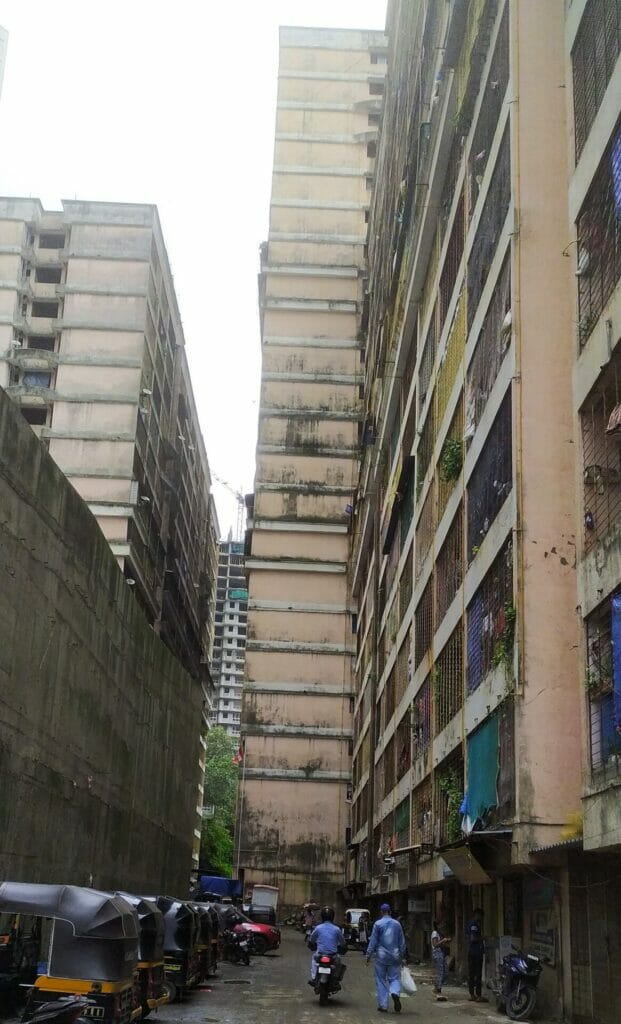

Though a number of garbage bins lie below their building, the provisional committee members of the Society are convinced that their building is cleaner and better maintained compared to other buildings provided by the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) Mumbai. Even so, at the first floor office of the society, residents — including the determined members of the MMSS — come together regularly to discuss issues plaguing their 22-storied building.

The walls of the society office display several complaints written to the local police station, to seek help in getting residents to pay the maintenance charges. Women of the MMSS even visit door-to-door, asking people to pay up maintenance dues so that the society can clear their pending electricity and water bills.

Squeezed between Dahisar metro station on one side and at walking distance from Dahisar railway station, the Jankalyan Society is a prime property, given its easy access to both the railway and Metro. Over 1700 slum dwellings were cleared to make way for the three redeveloped buildings. The first was granted possession in 2011 and was given Occupation Certificate in 2016. More SRA buildings are being constructed to provide in-situ housing for the residents of the slums that were cleared on the same location.

Maintenance of SRA buildings: Whose baby is it?

On paper, the developer is responsible for regular maintenance of the building till the building acquires the Occupation Certificate (OC). After the OC is granted, the developer is still responsible for major repairs for another three years, as it is considered to be part of the defect liability period. Thereafter, residents are entirely responsible for the maintenance.

The lifts, however, are maintained for 10 years by the developer and he is expected to provide for an annual maintenance contract (AMC) for 10 years for the lift services.

“Beyond the initial period, residents are expected to contribute towards day-to-day building maintenance. If they fail to do so, notices could be issued against them. Also, penal proceedings can be launched including confiscation of the house under the provisions of the Maharashtra Co-operative Societies Act,1960. The registrar of societies (western and eastern suburbs) is the appellate forum to address issues of SRA building societies,” says Satish Lokhande, CEO of SRA.

And yet, societies such as Jankalyan find it a huge challenge to meet the cost of maintenance through resident contributions, as the latter often falter on payments due to genuine affordability issues.

Read more: 27 years on, Mumbai’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) has failed to deliver

A continuous struggle

Ramkishan Mehra, a provisional committee member from the Jankalyan Society no. 2, points out how his building is struggling to maintain the premises. The building has 456 flats in all — 12 flats of 269 sq ft each, lined up across long, dark corridors in every floor, a la the old Mumbai chawls.

“We have pending dues worth Rs 19 lakh, which includes water bills worth about Rs 7 lakhs. Thankfully, the water department has a provision for accepting part-payments of bills and that sees us through. We keep paying small amounts and that keeps us going. Otherwise, it would have been difficult to clear the huge bills that have piled up,” says Ramkishan.

Now that their building more than 10 years old, the onus of maintenance is entirely on the residents. But they did not have it easy even in the initial years, when their building was maintained by their developer. The residents recall how they had to take a morcha to the local municipality ward office to demand that their developer cough up his share of the water bills and other pending dues.

On another occasion, electricity connections were disconnected due to pending dues and could be restored subsequently only after part-payment of dues.

Complicated issues plaguing maintenance issues in SRA buildings are not isolated incidents but rather the norm, according to Madhu Chavan, former president of the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) and housing activist. “Many SRA societies are running into large debts, because of the inability of residents to pay maintenance charges. It is not unusual to find them approaching elected representatives, seeking aid in settling bills,” he says.

It is not just regular running costs but legacy dues too, that add to the burden. “Though SRA rules mandate the developer to clear all dues before handing over possession to the residents, the reality is that often developers leave pending dues which are inherited by the residents. Often, residents find out about these liabilities only after they have already moved in,” says Dahisar legislator Manisha Chaudhary.

Affordability issues: A complex scenario

“We did pay for basic services even back when we stayed in our slums, but they were marginal charges and affordable. We paid around Rs 100 per household for water supply and another Rs 150 for common light charges and about Rs 50 for the person who kept toilets clean,” says Pravin More, another provisional committee member. He points out that many of the residents here work as domestic help, or are in informal jobs with earnings ranging between Rs 10,000 and Rs 40,000 a month. For them, shelling out Rs 1000 every month for maintenance is a strain.

The building residents estimate that they need roughly Rs 3 lakh per month for upkeep of their SRA building. “Apart from the Rs 2 lakh needed for the electricity and water bills, we also need to spend Rs 40,000 for paying salaries to at least two watchmen, a pump operator and a cleaner. While the monthly outflow amounts to this, the total maintenance inflow hardly adds up to even Rs 1.78 lakh,” explains Anil Bankar.

“Maintenance costs shoot up because of the huge electricity needs for basic functioning in SRA buildings. Whether it is the lifts needed for mobility in high rises, or the water supply network, these basic critical services are huge guzzlers of electricity. Water needs to be pumped up to the higher floors. All these add up to significant costs that make it unaffordable for the average slum dweller to stay in SRA buildings,” says a water policy analyst, who didn’t want to be identified.

Unable to afford the maintenance charges, many slum dwellers opt out of the SRA buildings. “People with low or irregular income try to escape the burden of maintenance charges by selling their SRA flats and choose to move back to other slums or to distant suburbs. Others put out their flats on rent and live off that income. Since selling or letting out of SRA flats for ten years is barred, this arrangement is often done illegally,” explains Pravin.

Needless to add, those who move in on rent or purchase these houses illegally, are often lured by the cheaper cost or rentals but eventually fail to pay timely maintenance costs.

“Developers being profit-oriented tend to neglect the needs and concerns of slum dwellers. Inept planning and substandard quality of materials used in SRA buildings result in maintenance issues, which occupants do not have the resources to address effectively. Since such issues often arise after the developer has handed over the building, it becomes even more difficult for the occupants to rectify them,” points out architect Anuprita Dixit, a town and regional planner, who serves as a design director with IMK Architects.

A recent instance was seen at a Kurla SRA building, where a major fire caused by a defective electric circuit left residents without power. The residents now stare at repair expenses worth Rs 5 lakh, which is nearly impossible for them to arrange, as most of them work as domestic helpers.

Possible solutions for SRA maintenance

Speaking to residents, committee members and housing activists, one can list some basic steps that could ease this situation:

- The government should conduct a regular review of the corpus fund formed at the start of the development projects. Earlier the SRA would retain the corpus, to which the developer also contributes, and disburse only the interest to the SRA societies for maintenance.

However, the SRA has now decided to handover the entire corpus to the resident societies soon after the OC is granted. There is however a need to ensure that the amounts and contributions are commensurate with increasing maintenance costs. - Developers should be held accountable for providing rehabilitation housing of good quality, comparable with their for-sale projects, so that regular maintenance costs may be minimised.

- Follow a carrot and stick policy — reward well-maintained SRA buildings with concession in property taxes.

- Give slum dwellers a clear idea at the outset about the kind of maintenance costs involved in living in a SRA building.

- Allot free houses, but get SRA housing beneficiaries to contribute towards a maintenance fund upon allotment.

We shall look into some of these suggested measures and what they entail in more detail in a follow up to this article.