Mumbai’s perennial struggle with routine waterlogging and catastrophic floods is the result of several limitations in the city’s storm water drainage system. This includes its reliance on its riverine ecosystems of which the Mithi River is a key component.

The Mithi is an urban river whose course has been trained and altered over the years, for almost its entire 17 km stretch. Channelizing the Mithi river for effective flood-risk mitigation has altered its capacity in several places, the impact of which is borne by those who live and work on the riverfront.

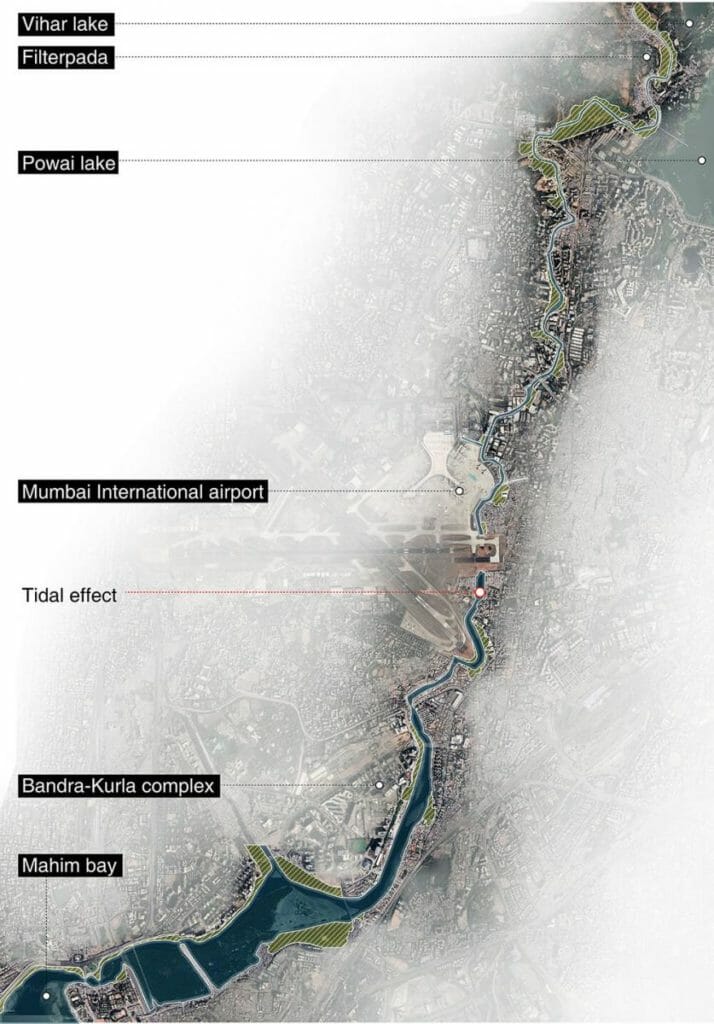

In the sweltering month of May, Abhijit Waghre began his walk to gain a deeper understanding of Mithi’s watercourse. The Mithi originates from the Vihar Lake outfall and has an inlet from Powai Lake further downstream. The upstream catchment area has three lakes— Tulsi, Vihar and Powai.

The region, just after the Vihar outfall, is dry during the summer months, consistent with the natural state of the river. Barring this short upstream stretch between Vihar Lake and Filterpada, a notified slum, that still seems to preserve the riverine ecology of the Mithi, the river bears no resemblance to its natural form further downstream. This is the only place where the Mithi is accessible to the public when it still bears some semblance to a river.

The first settlement, immediately downstream of Vihar Lake, is Filterpada. Following along the river, one can see piping that was originally meant to serve as storm water drainage which now carries wastewater and other effluents from nearby settlements into the Mithi.

Read more: Here’s how Mumbai’s most polluted river is being cleaned up

Over the years, people and businesses have settled on the riverbanks, severely restricting access to most of the riverfront.

Retaining walls are typically constructed along riverbanks to secure the edges between two ground surfaces of different elevations. Mithi’s retaining walls, however, have a specialized role to play, where they are used to channelize or train the river’s course for flood control.

However, there are missing links that interrupt what ought to be a continuous stretch of infrastructure. These arise due to various reasons, such as breaches caused by the placement of utility pipes across the riverbed (illustrated in photo below) or breaches arising due to delays in wall construction. For settlements abutting the river, this results in increased vulnerability to flooding, resulting in routine loss and damage.

Closer to the Mahim Bay the river is impacted by tides that increase water levels even during the dry season. The lack of a retaining wall here leaves communities vulnerable to routine inundation, especially during high-tide periods on extreme rainfall days.

A common engineering flood measure is to maintain the river’s conveyance capacity by regularly removing silt deposits. There are (possibly temporary) breaks in the wall at some locations to enable access for desilting machinery to the riverbed.

Breaches in the retaining wall seen at the time of the walk — at Saki Vihar Road (west of Powai Lake), Marol (downstream from Powai Lake) and the entire downstream stretch (beginning at the airport) — brings to question the reliability of retaining wall as a flood resilience measure.

Challenges in managing the riverbed

Training the Mithi has greatly altered the riverine ecosystem and compromised its natural flood resilience capacities.

Building retaining walls, as a flood protection measure, comes with its own challenges. For one, equipment required to build the retaining wall can be used only from the riverbed. So temporary ramps are built along the riverbed using soil to enable construction vehicles to access the riverbed.

In several places, the deposited soil remains in the river. This causes irreversible changes to the riverbed and creates bottlenecks in the river’s natural course, reducing its capacity as a flood resilience measure.

It is evident that a heavy dependence on desilting and channelizing the river, are increasingly becoming impractical and obsolete as flood control measures. It is time to think beyond mere maintenance methods for improving flood resilience. As we dive deeper into the Mithi, we will examine other aspects of the river crucial to the planning and design of Mumbai’s flood resilience strategies.

The original version of this article appeared on WRI India’s blog on August 17th, 2022. Views expressed here are the authors’ own.