Coastal cities have been centers of growth and development for centuries, but the same areas that once thrived are now vulnerable to the consequences of climate change. Megacities like Mumbai and coastal cities across the world are particularly at risk as the global temperatures increase. As the sea levels rise, they pose unprecedented risks of floods and storm surges, affecting human lives and property.

By 2070, Mumbai is projected to be home to over 11 million people in areas susceptible to rising sea levels and heightened flooding. That is almost four times more than current exposed population of 2.7 million. These vulnerable residents will face the risks to their homes, livelihoods and their basic safety.

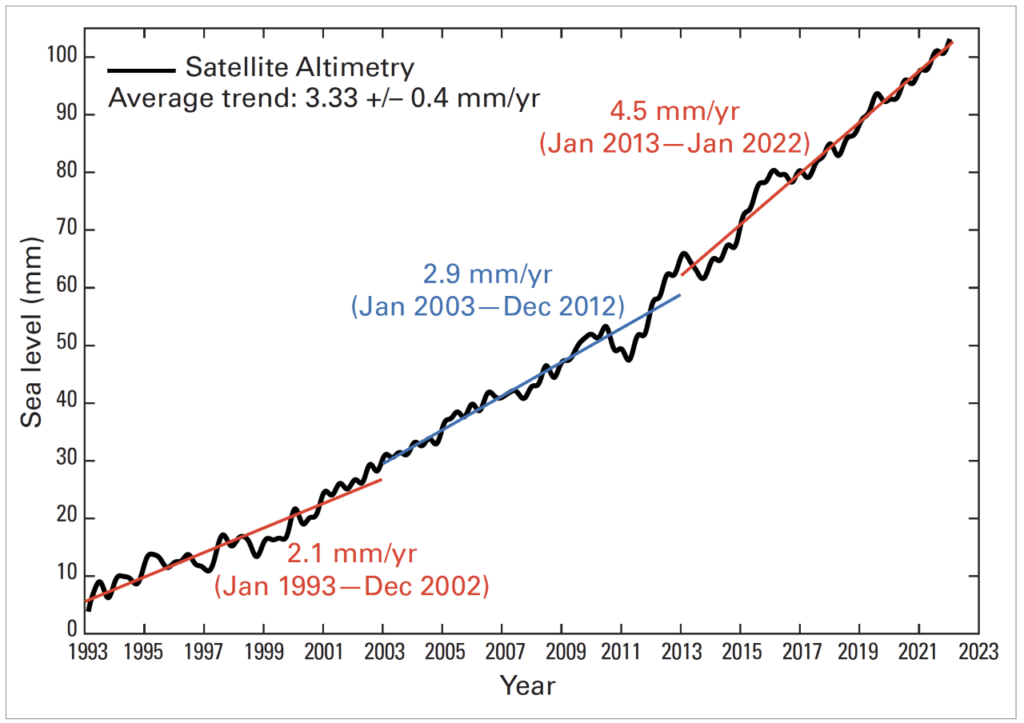

According to a report by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), sea levels rose by 4.5 mm a year between 2013 and 2022, over three times the rate between 1901 and 1971. This accelerated pace of sea-level rise poses a significant threat to numerous coastal cities worldwide, and Mumbai, the financial capital of India, is among those most vulnerable to its impact.

What’s causing the rise in sea-level?

The WMO, a specialised agency of the United Nations with a mandate that covers weather, climate, and water resources, said that the increase in sea levels is attributed to various factors, including the loss of ice on land, melting glaciers and ice sheets, and thermal expansion from ocean warming.

According to the WMO, thermal expansion accounts for 50% of the sea level rise observed between 1971 and 2018. The warming of the oceans causes the water to expand, resulting in an increase in sea levels.

Additionally, the loss of ice from glaciers contributed 22% to sea level rise, while ice sheets contributed 20%. Changes in land-water storage, such as the depletion of groundwater and reservoirs, accounted for 8% of the observed sea level rise during the same period. The rate of ice sheet loss has increased four times between 1992 to 1999 and 2010 to 201, having a direct impact on rising sea levels.

Coastal cities like Mumbai and others need to address climate change to protect vulnerable communities.

Read more : Documentary portrays worsening floods in Mumbai over years

Challenges for Mumbai

Mumbai, once comprised of seven separate islands, was shaped through reclamation of waterlogged areas. The reclaimed spaces, situated below the high water level, now face a challenge during prolonged rainfall (7–10 hours) coinciding with high tides. This prevents water evacuation into the ocean, leading to flooding in low-lying regions.

Apart from these challenges, rampant construction and deforestation of urban areas, further worsen the situation.

Journalist Pamela Cheema, AGNI (Action for Good Governance and Networking in India) Coordinator and Powai ALM, criticises the government’s approval of forest exploitation. Her organisation, AGNI, had taken a stand against the coastal road project, as she believes it will inevitably be submerged due to rising sea levels. “Despite the project’s high cost, we advocate for its termination, considering it detrimental to the city’s well-being. Our plea calls for prioritising the protection of these critical areas to safeguard Mumbai from the impacts of climate change,” she says.

Pamela advocates for the protection of the green lungs. “Do not touch SGNP and Aarey forest,” she says, because they can absorb increased flooding caused by climate change. She opposes the construction of the metro-3 depot at Aarey and twin tunnels in SGNP, as well as any development on the crucial salt pans that aid in flood mitigation.

“Mumbai needs to adopt a multi-faceted approach that integrates early warning systems, disaster risk reduction, and community engagement. Strengthening infrastructure, improving drainage systems, and implementing effective land-use planning can reduce the vulnerability of Mumbai’s neighbourhoods to flooding and landslides. Simultaneously, educating and empowering communities to respond and recover from these events is crucial for resilience,” says Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology.

Increased FSI near seafront

In 2021, the Union environment ministry gave the green signal to the eagerly-awaited Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP) for Mumbai, including its suburbs. Prior to this, the Coastal Regulatory Zone (CRZ) restrictions had made any revamp near the coastline challenging, allowing only a base floor space index (FSI) of 1.33 in the island city and 1 in the suburbs within 500 meters of the high tide line and 150 meters from the bay.

With the relaxation of these regulations, Mumbai is poised to witness a transformation with the potential construction of multiple skyscrapers facing the sea. Builders will be granted nearly two and a half times the developmental rights on such plots, guaranteeing a minimum FSI of 2.50.

Pamela says it effectively grants permission to build right up to the water’s edge, a move she considers misguided, given the increasing frequency of extreme weather events. She urges the government to reconsider these permissions and take into account the potential implications on the city’s environment and resilience to climate change.

“Mumbai floods are more of a management problem due to unplanned development than a climate change problem. We need to redesign our cities such that they are resilient to the intensifying floods,” says Roxy. “If Mumbai’s population is going to double by 2050, this will go hand-in-hand with a corresponding surge in urban development. Any development can be an opportunity to redesign the city considering “future” climate challenges. Flood maps should be prepared based on 2070–2100 climate change projections to safeguard the city from worst-case scenarios in the future.”

Other coastal cities managing sea rise level

When cities flood, in addition to often devastating human costs, real estate is destroyed, infrastructure systems fail, and entire populations can be left without critical services such as power, transportation, and communications.

Bangkok, a metropolis of over 14 million people, lies in the coastal plain of the Chao Phraya river. The southernmost region, with an elevation of about 1 meter above mean sea level, features a very flat and low surface formed as a tidal and deltaic plain. Due to sea level rise, the drainage conditions have worsened over time.

To mitigate flooding in Bangkok, various measures have been implemented such as construction of dams and reservoirs, installation of pumps and discharge canals, upgrading existing drainage systems, developing new water storage capacity within the city, and restoring mangroves. These efforts aim to improve the urban flood defense system and reduce the impact of floods in the coastal city.

In China, 16 pilot cities, including Tianjin, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, have been selected to embrace the concept of Sponge Cities. A ‘Sponge City’ is defined as a city that strategically integrates urban flood risk management into its urban planning policies and designs. The primary objectives of the Sponge City concept are centered around restoring the city’s ability to efficiently manage rainwater through absorption, infiltration, storage, purification, and drainage while striving to mimic the natural hydrological cycle as closely as possible.

As a way to prevent flooding, New York City, in partnership with the federal government, is reconstructing parks and communities from East 25th Street to Montgomery Street as part of the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project.

The $1.45 billion project, which began in the fall of 2020 and is set to be completed by 2025, will create a 2.4-mile “flood protection system” consisting of floodwalls and floodgates, as well as elevate parts of the region by up to 9 feet, to keep the storm surge out of the neighbourhood.

Warmer days ahead

According to a report by the WMO last month, there is a 98% likelihood that at least one of the next five years, and the five-year period as a whole, will be the warmest on record.

“A warming El Niño is expected to develop in the coming months and this will combine with human-induced climate change to push global temperatures into uncharted territory. This will have far-reaching repercussions for health, food security, water management and the environment. We need to be prepared,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas, in the report.

According to WMO, the global average sea levels have risen faster since 1900 than over any preceding century in the last 3,000 years. The global ocean has warmed faster over the past century than at any time in the past 11,000 years.

The rate of sea level rise has doubled since 1993. It has risen by nearly 10 mm since January 2020 to a new record high in 2022, according to WMO’s provisional State of the Global Climate in 2022 report. The past two and a half years alone account for 10 percent of the overall rise in sea level since satellite measurements started nearly 30 years ago.

Irreversible global warming

“In a historic development, the world has witnessed an average increase of 1°C over the span of just five years, an occurrence never before recorded in the history of mankind. This alarming rise in global temperatures, now deemed irreversible by the WMO, serves as a dire warning about the escalating impact of climate change,” says Girish Raut, a senior environmental activist.

During the pandemic days, he says, as industries, factories, vehicles, and human activities in general came to a standstill, a remarkable transformation unfolded before our eyes. The environment began to heal itself, with cleaner air, reduced pollution, and signs of nature reclaiming its spaces.

“Urgent and collective action is required to curb greenhouse gas emissions, conserve biodiversity, and develop resilient infrastructures. Failure to act decisively now could result in irreversible consequences for future generations. We must prioritise this issue and take global action now before it becomes too late,” he cautioned.

Urgent action required

Environmentalists and scientists says Mumbai must adopt a unique approach by prioritising biodiversity preservation alongside developing robust infrastructural defenses to combat the challenges of rising sea levels and flooding.

Preserving Mumbai’s urban forests, such as Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Aarey Forest, are urgent priorities.

Rather than pursuing short-term construction and increasing the FSI, the city must invest in long-term solutions that can effectively withstand climate challenges. Sustainable infrastructure that can endure rising sea levels and extreme weather events is crucial for ensuring the safety of Mumbai’s people, say activists.