By March 2020, along with the rest of the country, Mumbai went into a severe lockdown. Social distancing, wearing a mask and hand washing were necessary precautions, and access to them, the need of the hour. A majority of the population did not – and still doesn’t – have access to safe water or sanitation, nor the privilege of technology.

This exclusion in the time of a public health crisis is not new. Bombay has seen several epidemics in the past, but what is often overlooked in the discourse on public health is that many such diseases are waterborne. Furthermore, they are exacerbated by the lack of infrastructure planning that is sensitive to the needs and priorities of different communities that make up Mumbai.

In 2020, during the pandemic, around 40 professionals in the water sector in Mumbai came together to launch Mumbai Water Narratives and a collective virtual exhibition ‘Confluence’, tracing a journey from heritage to public health, in response to this crisis.

Water is piped, Sewers are laid

State intervention in public health can be traced as far back as to the early 1800s, when a series of cholera epidemics ravaged the Indian Subcontinent. This was one of the early challenges of the British administration in Mumbai. Frequent epidemics meant significant damages to life, labour and infrastructure, and therefore had to be dealt with infrastructural and public health interventions. The prevalent public health theory at that time placed the blame of the crisis on ‘miasma’ – which meant an invisible, noxious odour that public health officials believed was transmitted through air and from the ‘unclean and unhygienic’ conditions of native colonies in Bombay. In response to this, large scale sanitation reforms were initiated. In 1860, plans to lay out piped water supply from Vihar Lake, located near Vihar village on the Mithi River in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, were established, along with an upgrade of drainage systems in the city. By the end of 1800s, the Fort and Mazgaon areas were resewered, and a comprehensive Health Department was created in Bombay to take control of the public health crisis in Bombay.

The Epidemics Act comes into being

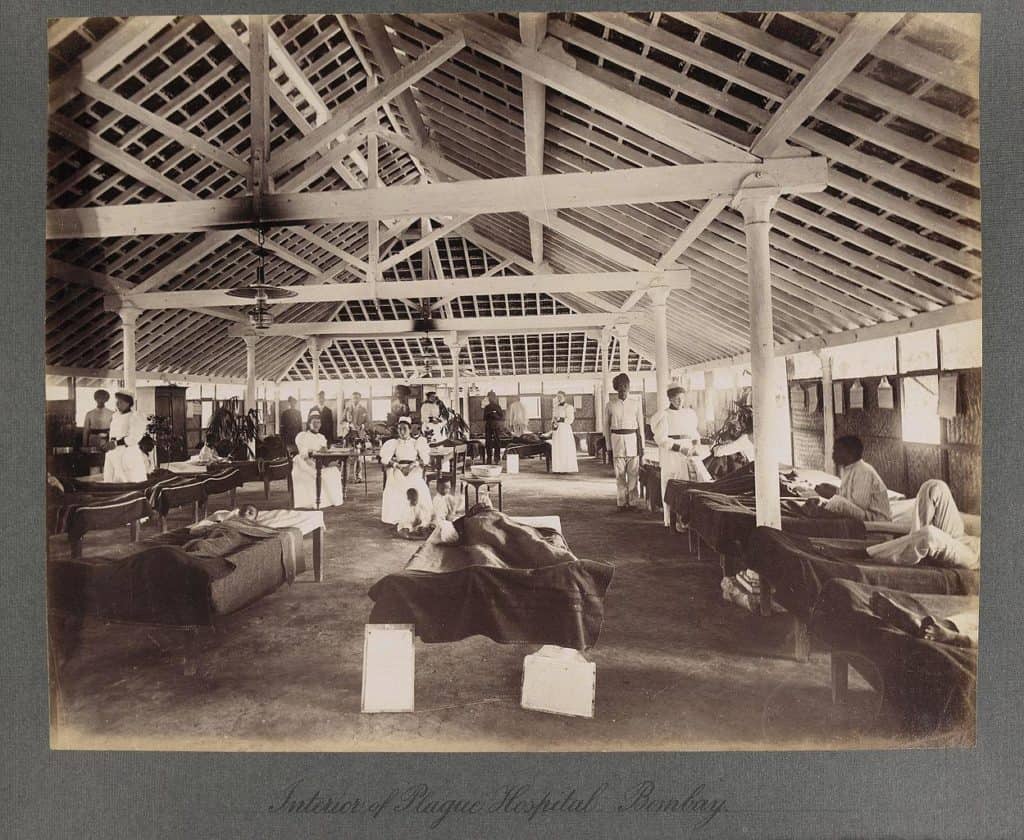

But the crisis in Bombay refused to subside. In 1896, a bubonic plague epidemic broke out in the city, presumably from a rat infestation in the naval dockyards. In 1897, the Epidemic Diseases Act was instituted in the city in response to the plague, which empowered authorities to adopt all possible measures deemed necessary to prevent the plague’s spread, including prohibiting gatherings, pilgrimages, transportation and the hoarding of commodities. The next year, the Bombay City Improvement Trust was created by the Health Department as a way to create large-scale planning and urban development interventions to decongest and improve sanitary conditions in the city. This included creating wide roads and avenues to allow sea breeze into the city, and using centrifugal pumps to wash the sewers with sea water. These developments were in the wake of scholarship that proved that the miasmatic theory was unscientific, and that the origin of diseases could be traced to specific points in time and place, and transmitted through bacteria, pests or other vectors. The locus of the disease thus had to be identified in any way possible.

Read more: COVID-19 mitigation measures have led to the neglect of one of Mumbai’s top killers

Malaria forces the closure of wells

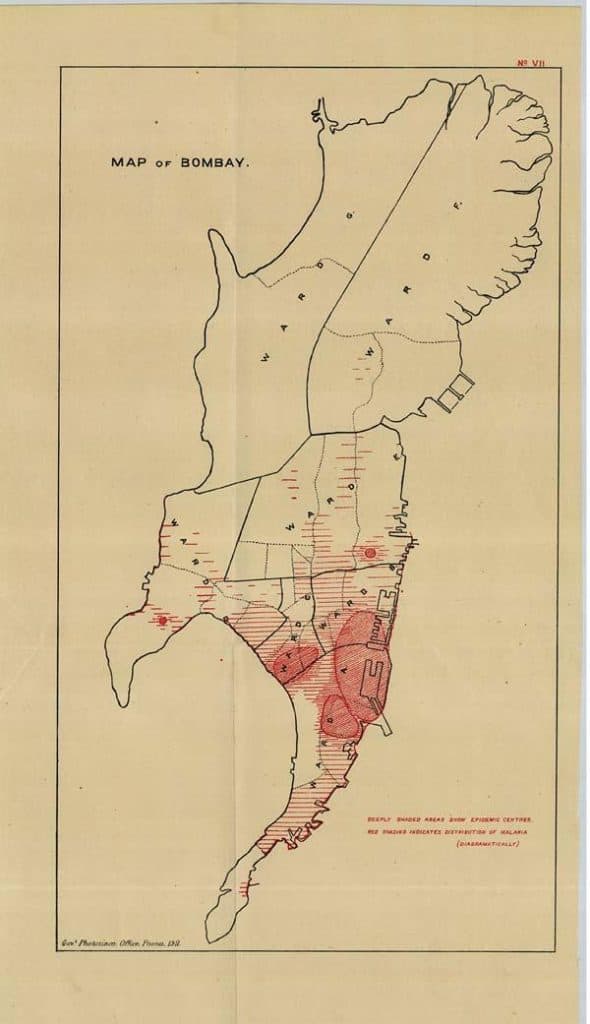

There was a dangerous vector in Bombay (and in the larger landscape of India and South Asia) that made the life of the colonial administration very difficult, and that was the female anopheles mosquito.

Malaria was prevalent in waves almost every year, and this was another public health crisis that the administration attempted to eradicate. Research in the early 1900s by Dr. Charles Bentley showed that the malarial mosquito breeds in stagnant water, and more importantly, in the many wells – shared and domestic- and ponds in Bombay. In spite of a piped water supply system, many native residents of Bombay continued to use their wells, presumably due to the fact that a charge was levied on piped water and there were several inequities in water distribution. However, in the wake of the Bentley report, tanks and ponds were filled up, and most wells in the city either had to be covered or filled. By 1940, of the 4000 wells in Bombay, only 1200 remained open. This number was to reduce significantly in the coming years. As time passed, the reliance of people from shared water resources to piped water became complete.

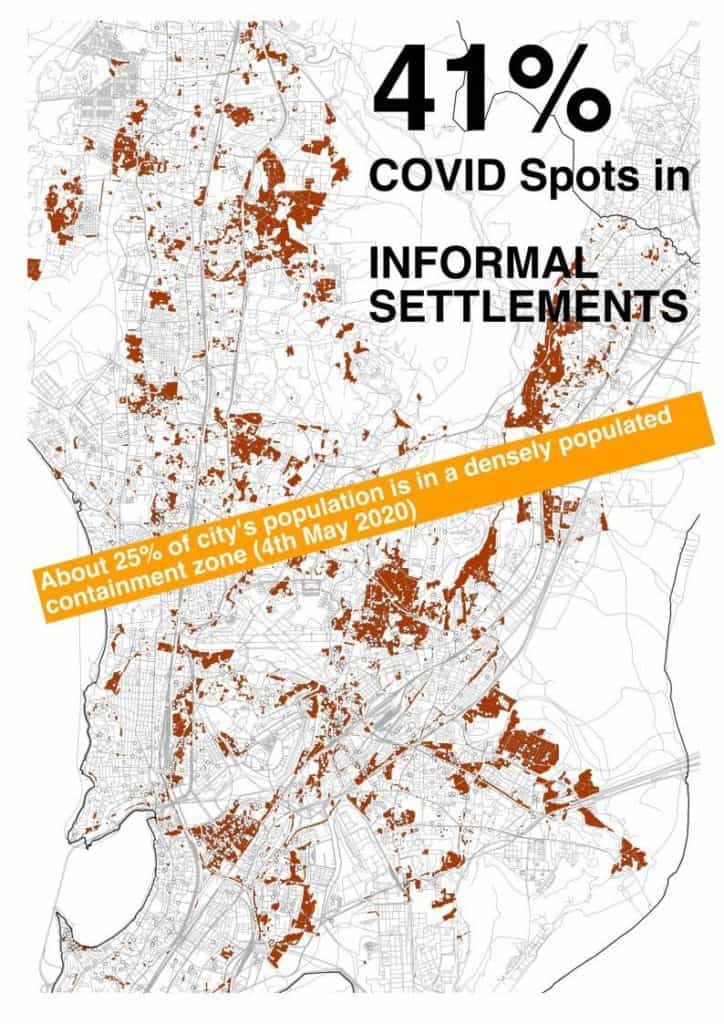

As India became independent, it grappled with old, continuing and new public health challenges. Malaria refused to subside, and tuberculosis and cholera outbreaks broke out from time to time. As Bombay developed, so did rampant informal settlements and inequity. Access to water was systematically denied to several informal settlements, and water itself became more and more scarce, reduced to time slots when water was available and a trickle when not. To add to that, Mumbai faces severe floods almost every monsoon. A scarcity of water and lack of access to sanitation cause UTI and transmissible diseases like E.Coli, diarrhoea, dysentery etc to those who are forced to rely on unclean public toilet infrastructure. On the other hand, an excess of water, such as during floods, leads to a substantial increase in the percentage of water transmitted diseases such as malaria. By 2013, a Eureka Forbes study had found that 83% of all diseases in Mumbai originated from water. When the covid pandemic hit in 2020, the public health infrastructure in Mumbai was already dismal.

A culmination of our history of Public Health and Water

In the rhetoric of handwashing and social distancing during the pandemic, what was intentionally forgotten was that several households in Mumbai receive only 45 mld of water in a day. If water is insufficient for essential activities such as drinking and cleansing, how would a practice of washing hands for 20 seconds every hour be sustained?

The pandemic also forced us to contend with the Epidemic Diseases Act again, which has more or less remained similar to the intent of 100 years ago, when it was created. Frequent lockdowns and harsh restrictions completely dismantled the fragile economic security of the informal sector, and even low to moderate income communities. The large-scale interventions to ‘sanitize’ the city affected native populations and influenced dense, urban, unsustainable settlements that continue to this day. Water and sanitation became commodified and were denied to a large part of the population.

It is up to us to acknowledge instances in history that have led us to where we are now, and correct our public health narrative to be more inclusive, equitable and resilient to future crises.