Distances are measured in time in Mumbai. Mulund is 30 minutes away from South Mumbai in a fast local train and Vasai an hour. But how far is the Giri’s Geckoella from Kanjurmarg, or where are you most likely to spot Vigors’ Sunbird?

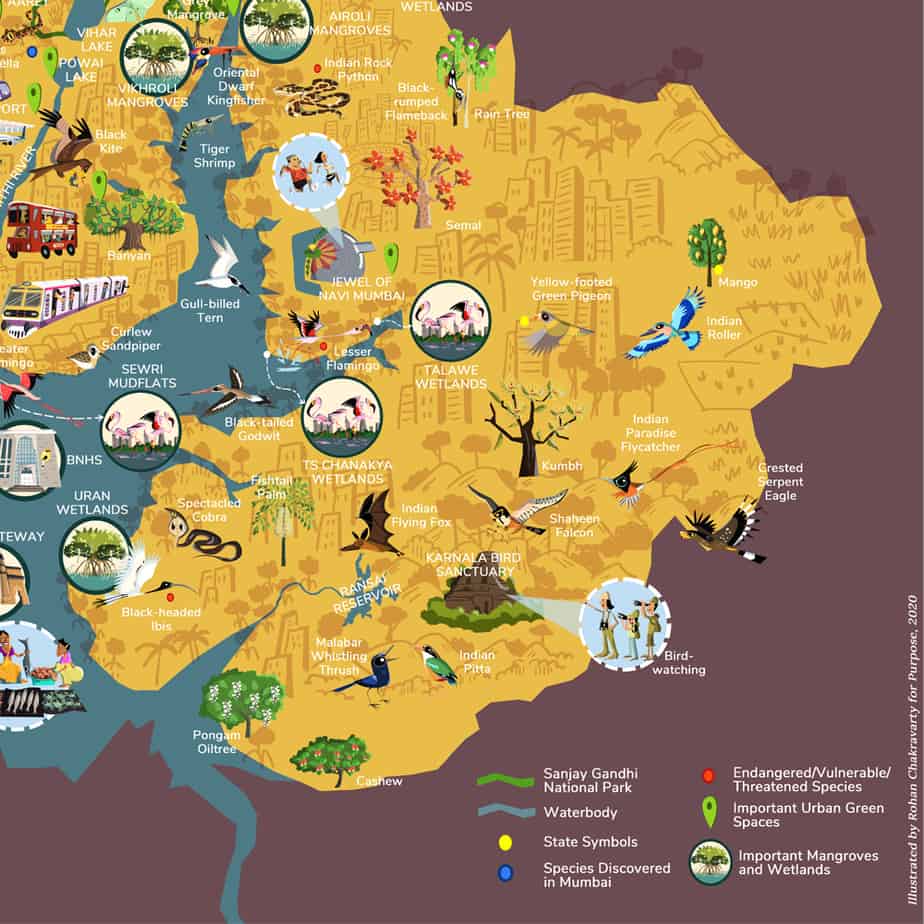

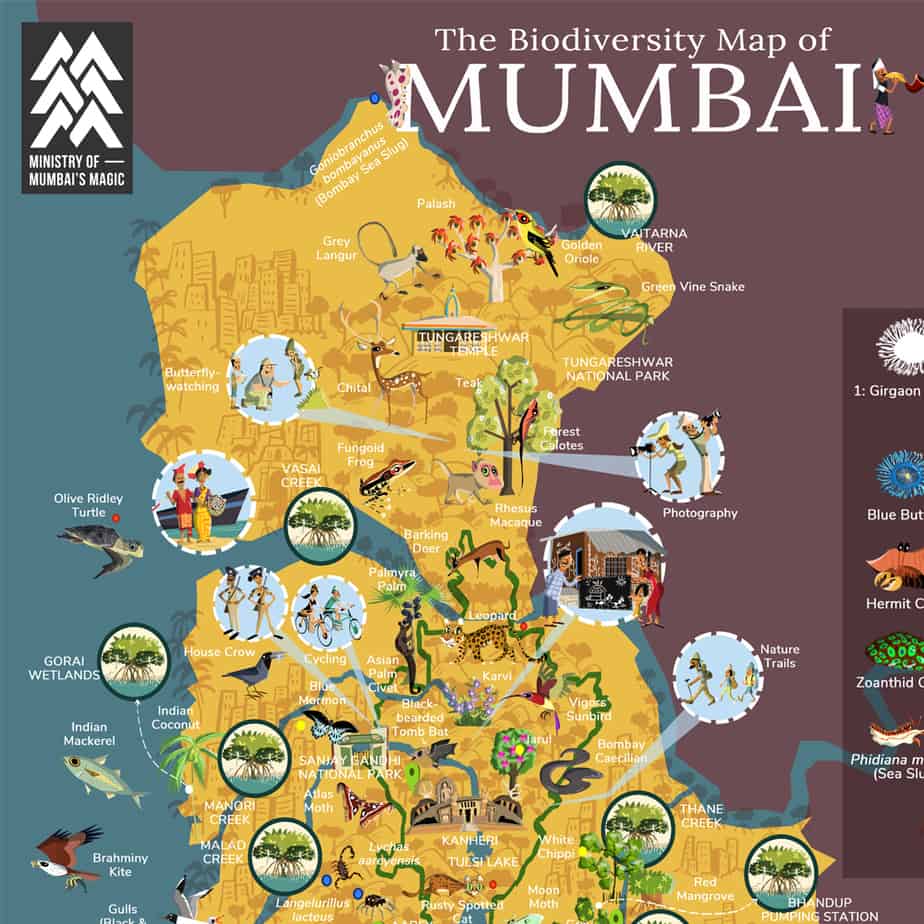

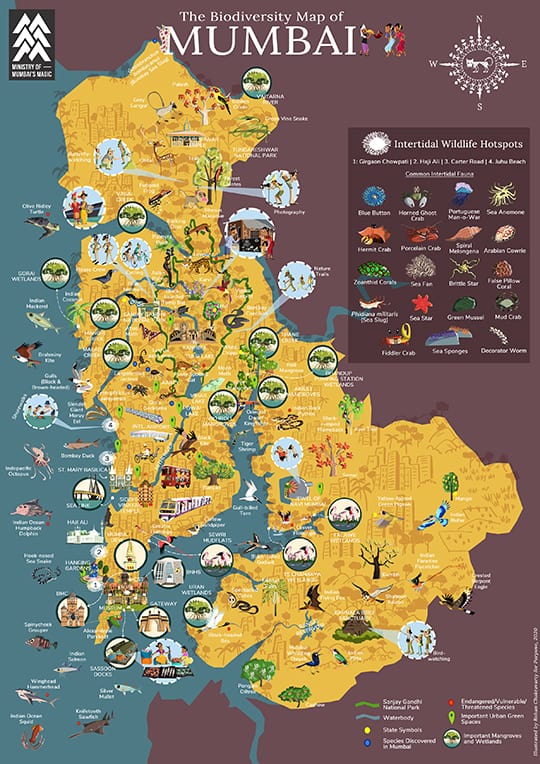

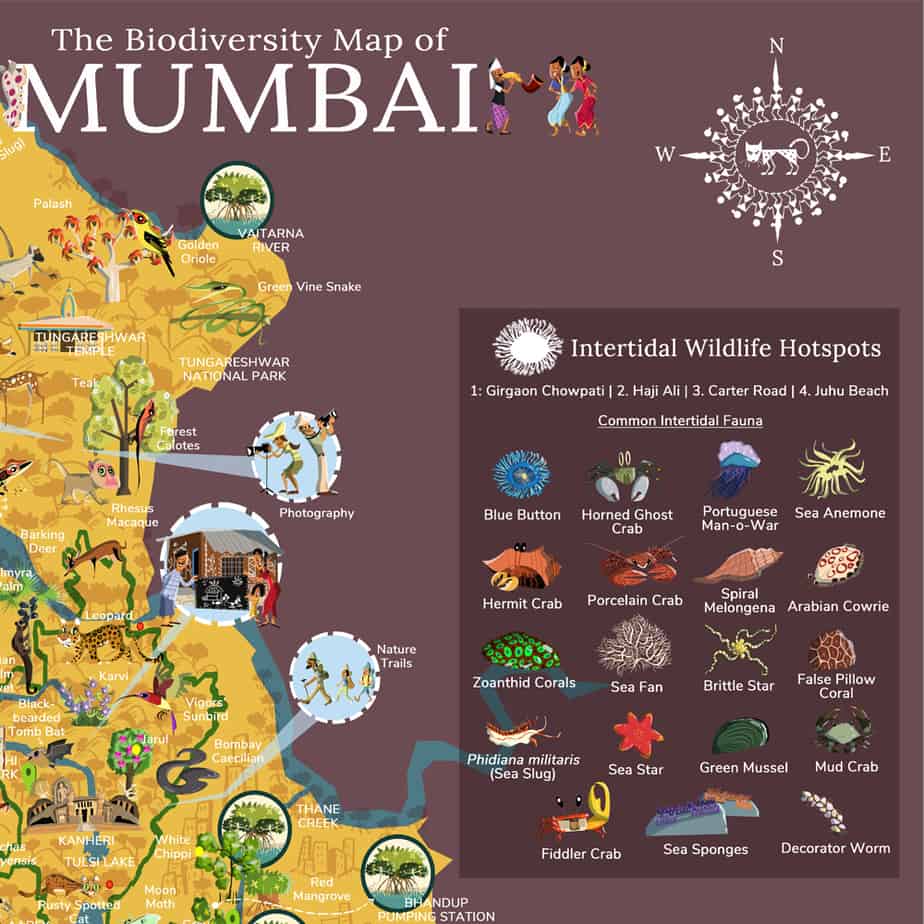

A biodiversity map, commissioned by a non-profit, Purpose Climate Lab (PCL), puts the city’s landmarks and its plant and animal life in perspective. This new map for an old world shows that along certain edges and nodes of Mumbai, the real landmark might be the city’s biodiversity.

We spoke to Rohan Chakravarty, the map’s creator, and Sonali Bhasin, Senior Strategist, Purpose Climate Lab, about the inception and journey of the map. Edited excerpts:

You are an award-winning wildlife cartoonist. And this is not your first map. How did this journey begin?

Rohan: The first map I made was of the Pakke Tiger Reserve in Arunachal Pradesh. It was a friend’s idea to distribute wildlife on a map. It’s not exactly cartographical but a more creative description of a place. Since then, I have worked on about 30 maps of national parks, tiger reserves, cities and countries. The Mumbai map was commissioned by Purpose (Climate Lab) for their Biodiversity by the Bay campaign.

Why does Mumbai need such a map?

Rohan: People know that Mumbaikars coexist with Leopards. Beyond that there’s not much information we retain or respond to. Biodiversity is not something people think of when they imagine Mumbai. That’s something I wanted to change.

Sonali: When you think of Mumbai, you think of skyscrapers, the beach or a lack of space, but it’s an incredibly biodiverse city. When we published the map, the idea was to get people who hadn’t thought about biodiversity or climate change before to start talking about it.

What went into making this map?

Rohan: I couldn’t conduct field visits because of the pandemic, so I read a lot and relied on existing information to execute this illustration. I have also visited Mumbai several times and am familiar with its architecture, history and heritage. The organisation (Purpose Climate Lab) also helped me with tribal depictions of Mumbai, which was one of the main motives of commissioning this map. The two main communities: Warlis and Kolis and their various sub-sects are being pushed to the margins by governments that exclude them from policy.

The map has received a tremendous response. What is it about a map as a tool that resonates with people?

Sonali: A map works because people can see exactly where they are in it. Mumbai is a familiar silhouette to a lot of people and we see maps of it all the time. But you never really see accha, this is where I live and this is where the Giri’s Geckoella lives. This is a good way to represent the species we didn’t know live next to us and all the indigenous communities that have lived in Mumbai far longer than we have. What I also love about a map is that it’s a great educational tool.

Rohan: Yes, there’s been a lot of buzz about this illustration. It’s got more traction as compared to my other work. That’s what Mumbai is all about – grand planning. The more eyeballs it catches the better is it for the project. For example, the city’s coastline, which is under threat from the coastal road project, is extremely biodiverse and rich. Some of the coral species found here come under Schedule 1 (of the Wild Life Protection Act, 1971). It’s a protection that the tiger enjoys. A lot of people don’t know about this. Now at a time when coral translocation is happening to facilitate the coastal road, a project like this (Purpose Climate Lab’s Biodiversity by the Bay), I hope, could push the government to reconsider.

What about the city’s biodiversity was a revelation to you while making this map?

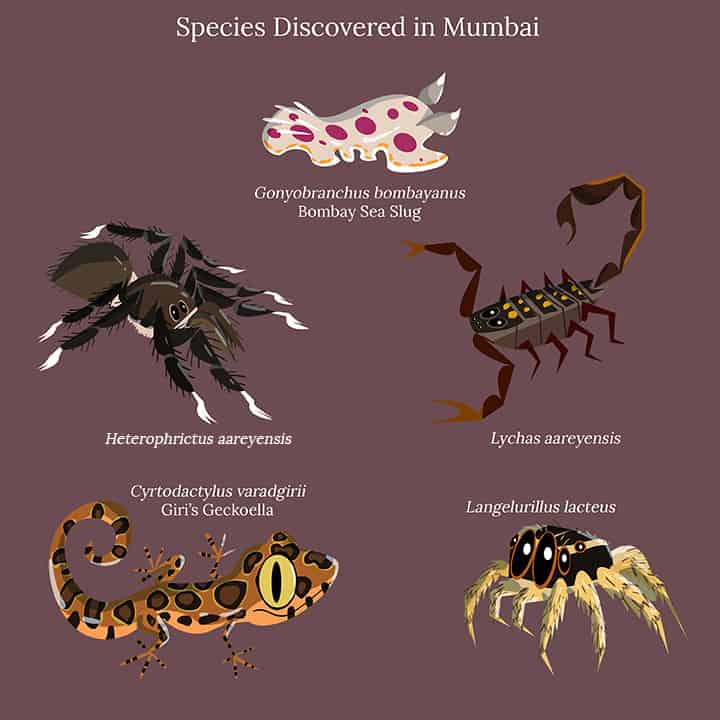

Rohan: Giri’s Geckoella, a new specie of scorpion (Lychas aareyensis) and two species of spiders (Langelurillus lacteus and Heterophrictus aareyensis). All these were discovered and described in the Aarey colony. I don’t think there are other records of these animals, which makes Aarey a spot of national importance.

And what does the map miss out?

Rohan: There’s a lot of birdlife that I couldn’t depict on the map. If you look at bird records in Mumbai, there are new birds, especially migratory birds, that show up every year. Mumbai has so much to offer even beyond this illustration.

The map has garnered a lot of interest. What next?

Sonali: We are working on an interactive webpage and are excited to launch that in a month or two. We would also love to explore partnerships with the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, the Bombay Natural History Society to see where else this could map to live – in front of parks around Mumbai, in universities, educational institutions.

Perhaps you could create micro maps across the city that lead to hikes and trails?

Sonali: That would be really cool. We could also do user-generated maps, encouraging people to go out and explore the biodiversity around them.

Is there a fear that people will see this map or any other environmental cartoon or illustration, appreciate it, and move on?

Rohan: Cartoons reflect the very mood of the country on a particular day. And that’s what my cartoons do in an environmental scenario. Over the years, my work has been reaching people outside the wildlife or science sphere and engaging people from various backgrounds. Creative communication is collectively beginning to change the picture. A lot of young people (today) are leading environmental movements and protests. The time that people were comfortably distant from the environment around them is gone and a huge share of the credit goes to creative communication of all kinds.

Sonali: The map is a great starting point. Our goal was to bring new people into the conversation and have new people take ownership of the biodiversity in their city. We have worked with musicians and artists who have not talked about this before. We have also organised webinars and talks. We are building a ladder of engagement. You start small by making conversations happen and then you build that into impact. Every time someone comments on the map and says that they didn’t realise what sort of city they lived in, that’s a form of impact for us as well.