Mumbai generates about 11,000 tonnes of solid waste every day, according to estimates from Central Pollution Control Board, 2015-16. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) is formally responsible for its management.

The unexpected entry of COVID-19, has pushed solid waste management to the background. While the focus is on minimising the spread of the virus and saving lives at this time, we cannot ignore the waste that we are continuing to increasingly generate due to the pandemic.

In order for us to leave a better planet to the future generation, we have to roll up our sleeves and get our hands dirty. Today, I shall tell you the story of how I learnt solid waste management techniques from the best in the industry.

Tomorrow, read part II where I give you tips to implement these methods in your living spaces and reduce waste. And I will also tell you why the pandemic disrupted our plans to implement solid waste management.

Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016

In October 2017, the MCGM started implementing the new Solid Waste Management Rules of 2016, which included segregation of waste at source, self-disposal of dry waste to recyclers and mandatory handing of wet waste (compositing, biogas, etc.) within the premises for those generating above 100 kg of waste per day. (The rules were revised and amended in 2018)

Over the next few months, everyone was looking for quick fix methods to organise themselves to segregate waste and then to get rid of it. Waste management consultants and those providing waste handling solutions were in high demand. Many bulk generator societies in the city had started following the rules after investing lakhs of rupees on composting machinery and other infrastructure. Those that weren’t, were receiving warning notices and then being penalised with monetary fines, but many got away.

Apart from trying to clean up the city, the objective of the new rules was to reduce the quantity of waste going into landfills at Deonar and Kanjurmarg. The MCGM was under immense pressure to close the Deonar Dumping Ground by December 2019.

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) has, in fact, been pursing all municipalities to commit to deadlines to shut down their landfills.

In the beginning…

In May 2019, when Mr Praveen Pardeshi took over as Commissioner of MCGM, he realised that compliance levels and cooperation from housing societies were inadequate, municipal officers were seemingly helpless and there was no firm plan in place to shut down Deonar.

MCGM got an extension.

Mr Pardeshi decided to rope in Mr C. Srinivasan from Vellore, who is known in waste management circles for his simple and natural approach to handling waste.

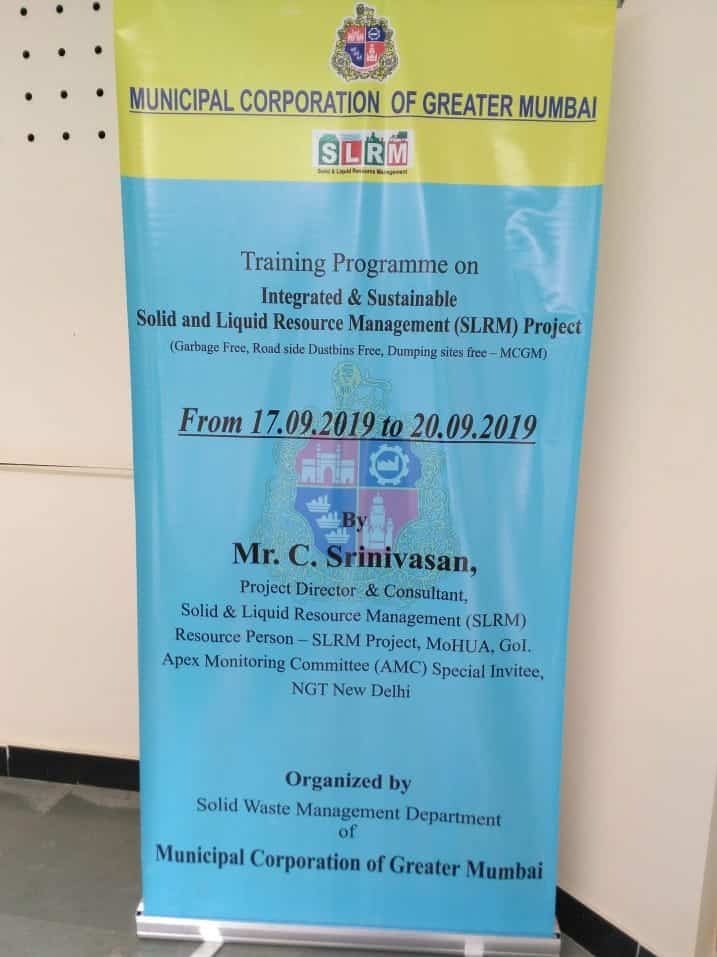

Mr Srinivasan is the Apex Monitoring Committee Special Invitee to National Green Tribunal (NGT), New Delhi and a resource person from Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India, that is implementing the Swachh Bharat Mission. In 2014, he was featured in the TV show Satyamev Jayate’s waste management episode.

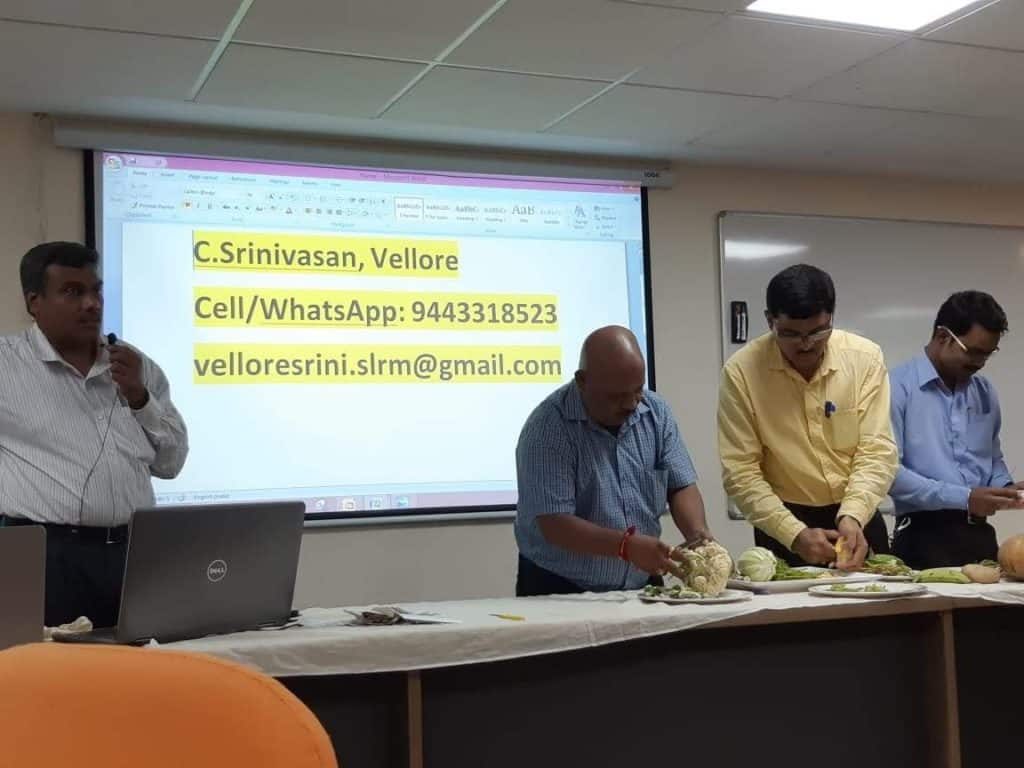

So in September 2019, I met Mr Srinivasan. He was brought to Mumbai for a 5-day programme. The first day, he spent visiting several waste management facilities across the city. The rest were spent in training officers, engineers and citizens on Integrated and Sustainable, Solid and Liquid Resource Management (SLRM).

I was one among those who attended the 2-day session.

During the session, Mr Srinivasan was confident that it would take two years with the SLRM Model for Mumbai to be garbage free, roadside dustbin free and dumping ground free. All this by investing in creating proper awareness among people, putting in place basic waste management infrastructure, training the sanitary workers and giving them the respect that they deserve.

What is the SLRM Model?

Solid and Liquid Resource Management (SLRM) is a decentralised waste management model. As per the SLRM model almost every element of “waste” can be reused in some way. So everything we call waste is actually a resource.

The model is not new. It is being implemented in many cities across India. For example, Vellore in Tamil Nadu, Ambikapur in Chattisgarh, Silchar in Assam, CRPF campus in Delhi and Mysore in Karnataka are early adapters.

Ambikapur was radically changed and now figures among India’s cleanest cities. While the framework of the model remains more or less the same, it is adapted to suit the area where it is implemented.

The SLRM model ensures that residents segregate at source, in their homes, as per the municipal rules. With large volumes of “waste” generated in a township on a daily basis, there is potential to process/utilize these resources, within the township itself rather than carrying it miles away. So the waste from every household is taken to an SLRM centre that is situated within the township.

There are different types of waste produced in residential areas – organic wet/kitchen waste, organic garden waste, inorganic dry waste, sanitary waste, bio-medical waste. Each is handled at the SLRM centre based on the local conditions. When treated in a timely manner, the waste remains useful.

- Organic waste is sorted into about 60 categories.

- The model aims to have much of the kitchen waste utilised by animals. The SLRM centre usually connects to gaushalas, piggeries, dog shelters, etc. This takes care of bulk of the organic waste leaving very little for composting. In Mumbai, gowshalas are currently not permitted within city limits. Biogas is the next preferred use of organic waste.

- Certain items such as flowers, citrous peels, egg shells, etc. undergo processing at the centre itself. They are used for the manufacture of organic products such as rangoli powder from flowers, cleaning agents from citrous peels, egg shell powder, etc.

- Garden waste which is also organic, is composted in local parks.

- Inorganic waste including plastic, paper, glass, metal, e-waste, clothes, shoes, toys, utensils, etc. undergo secondary and tertiary segregation (into about 170 categories) at the SLRM centre, after which they are packed and sent out to recyclers, factories and other places where they would serve as input material or reused.

- Sanitary waste is treated in a sanitary park (not incinerated), and serves as the base for tree plantation.

- Medical waste is sent to medical waste handling facilities.

The model ensures that everything that can be recycled is recycled. The material is sold for the best rates in the market. Nothing goes to the landfills. It creates employment and keeps the township clean.

Setting up an SLRM centre

- Space – The SLRM centre would be designed based on the space allocated. In a city like Mumbai, where space is at a premium, the centre can be designed as a multi-storied building. The centre can be spread across different sites as well.

- Infrastructure within the SLRM centre – The building will need electricity/solar power and water connections. It will also need furniture, segregation equipment, storage containers, etc. There will be one-time set-up costs and running costs.

- Manpower – Staff to work in the centre to carry out waste segregation and processing will have to be identified, trained and appointed. This will have to be done locally. For every 250-300 households, 4 staff would be required. The centre would work 7 days a week and could have workers in shifts for 24 hours.

- Transportation of waste from the societies to the SLRM centre – This can be done using MCGM’s help or finding local operators.

- Guidance and planning – The entire design of the centre’s activities would be done by Mr Srinivasan and team. They will define the processes, train staff, locate vendors, assign tasks to volunteers, etc. Once the centre is stable, which would take about 8-10 months, it will be handed over fully to local people to run.

- Funding and costs of running the centre – As this initiative would be relieving MCGM of a huge burden, it is expected that it would facilitate the running of the centre. Initial expenses will need to be met by MCGM and / or a common pool fund. Many societies in the area already pay a waste collection fee which would be given here (instead of where it currently goes). There are several sponsorship / fund raising opportunities for which local businesses and large corporations can be approached. Once the SLRM centre is running and the material is sold for recycling, the incomes would meet the expenses to a large extent.

- Administration – The SLRM centre will be handed over to a societies group (like a federation) and they will run it with the help of a self-help group or such. All societies will be a part of the federation and there will need to be a management team for administration and day to day operations.

Also read:

Opinion: Let’s not allow corona to defeat the fight to reduce plastic