“My children’s certificates, the first ever bike my son got on his own and our wedding album was among the many important things that we saw float away when more than 12 feet of water entered our home,” says Varadharajan as he recalls the nightmares of the 2015 Chennai floods. Varadharajan lives on the floodplains of Mudichur Lake in Chennai which was one of the worst hit areas during the 2015 floods when the water was released from Chembarambakkam lake into Adyar river.

The 2015 floods came as a wake-up call for the government and the residents of Chennai. Since then, many projects about lake restoration have been taken up with the view to mitigating urban flooding and improving the holding capacity of many large lakes in the city.

In a recent move, the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) and Tamil Nadu Water Resource Department (WRD) have identified 10 lakes in Chennai and are likely to spend Rs 100 crores to develop them.

The aim is to strengthen the blue-green infrastructure of a city as it helps tackle climate change and urban heat island effects.

The ten lakes that are part of the project are

- Perumbakkam

- Retteri

- Mudichur

- Madambakkam

- Sembakkam

- Ayanambakkam

- Velachery

- Adambakkam

- Puzhal

- Kulathur

Given the significance of restoring the lakes in Chennai, especially after seeing the massive floods of 2015, it becomes pertinent to ensure the process of restoration serves to benefit the people while also not impacting the lake’s natural ecosystem.

Read more: How to go about lake restoration: Learnings from efforts in Chennai

Previous eco-restorations of lakes in Chennai

Often when lake restoration works are taken up in Chennai, the term ‘eco-restoration’ makes the headlines. Though there is no standard methodology prescribed for water body restorations as such, the Central Pollution Control Board, in 2019, published the Indicative Guidelines for Restoration of Water Bodies in compliance with a National Green Tribunal (NGT) order. Following this, the Tamil Nadu government also came up with an action plan in 2019 adopting the said guidelines. When asked if the participants of the Lakefront Reconnect Design Competition were given the said guidelines before submitting the design proposal, they responded negatively.

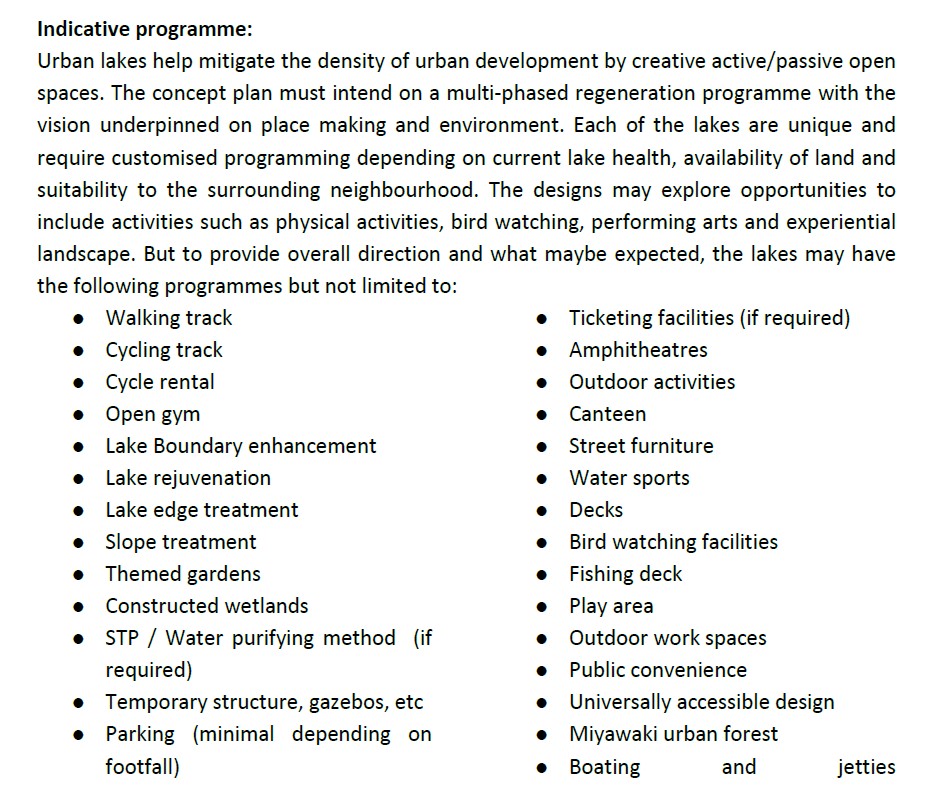

Meanwhile, the experts in the field also point out that the ‘Chetpet model’ of eco-restoration is followed for other lakes in Chennai as it works well in terms of generating revenue. According to a news report in June 2023, the Chetpet Lake which was converted into an ecological park generates a revenue of Rs 8 lakhs per month with an average footfall of 20,000 visitors. The park has multi-level car parking, a play area for the kids and a guest house in addition to the leisure activities like boating, sport fishing, rock climbing, a three-dimensional amphitheatre and a virtual reality show space. CMDA’s design brief more or less covered the same ambit of activities for the lakefront development project of the ten lakes in Chennai.

Commenting on this, Harris Sultan SA, a state body member of anti-corruption watchdog Arappor Iyakkam, says that Chetpet Lake has neither an inlet nor an outlet. Whenever it rains in Chennai, one can find stagnant rainwater on Poonamallee High Road, which is supposed to drain into the lake. “A lake should have a catchment area which is supposed to take in water, store it and send out the excess water in case of floods. It should also be a haven for both humans and the flora and fauna. However, the eco-restoration model adopted in Chetpet Lake is a failure as does not serve the purpose in an ecological sense. It is highly commercialised with more focus on human activities. The lake is nothing but a pool of water now,” he says.

He further adds that the ticketing system for these eco-parks alienates the local community from the lakes and makes it accessible only to those who have money.

“The walkways around the lake are supposed to be laid outside the lake. However, following the Chetpet model, the walkways, cycle lanes and all other commercial activities proposed in the name of developing the lakes are happening inside the lakes in Chennai,” he says.

Arappor Iyakkam also audited the Villivakkam Lake in Chennai which was highly polluted. The issue here was that the Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewage Board (CMWSSB) gave the Villivakkam Lake to Chennai Metro Rail Limited (CMRL) to dump the debris. Following the High Court order, around 2 acres of the Villivakkma Lake were handed over to the Greater Chennai Corporation for restoration. The GCC prepared a detailed project report (DPR) to restore the lake, according to which, the lake was to have some walkways and play areas for the children. However, later we saw that the GCC proposed an amusement park on the 10 acres of the catchment areas in the lake to build an amusement park. The argument put forth by the GCC was that they were going to deepen the lake so that they can use the other part of the catchment area for building an amusement park. “The Villivakkam Lake was originally 214 acres. It has now been reduced to 39 acres. Of this, if ten acres are taken for building an amusement park, there will not be any lake left,” says Harris pointing out that this is an encroachment of the lake done by the government.

While most of the lakes are encroached on by the government as mentioned in the above case, very often when we approach the court seeking action to restore the lakes in Chennai, the government first evicts the vulnerable people around the lakes citing them as encroachers. The places where the poor once lived, become parking sheds for the rich people in the same area. The current eco-restoration model of lakes in Chennai is meant for the elites in the society who can afford the parking charges and entry fee to access the lakes and not the poor,” adds Harris.

“Lakefront development is a welcoming move. But the water spread area should not be shrunk. Lakes do not require exorbitant amenities. All we need is a proper walkway and some parking facilities. Amenities like canteens inside the lakes are unnecessary,” says Sunil Jayaram of Chitlapakkam Rising, a registered non-governmental organisation that played a major role in reviving the Chitlapakkam Lake.

Read more: Saving lakes in Chennai: Why maps and physical markers are critical

Concerns around current plans for lake restoration

The CMDA called for an open design competition seeking design proposals from Architectural Design firms interested in participating in the Lakefront Reconnect Design Competition for the aforementioned 10 lakes in Chennai earlier in April 2023.

“We look forward to finding strategic designs with inventive and forward-thinking solutions that create genuine synergy between people, place and water,” read the competition brief.

According to sources in CMDA, as many as 63 design proposals were received. Of them, three to six firms were shortlisted for each of the 10 lakes in Chennai selected under the project. Financial bids have been invited from the shortlisted firms. The tender is to be awarded to the lowest bidder.

“We have finalised the bids for six lakes so far. The selected firms will now work on preparing the detailed project report,” says Anshul Misra, Member Secretary of CMDA.

An architect, who participated in the competition, says that his team visited the site before formulating the design. Every team was given a water body map in which the development zone was also marked.

“We are supposed to design the developmental activities only in that developmental zone. However, when we verified the map with the satellite image of the lake, we found that developmental zones were marked inside the lake. Since many of these lakes in Chennai have no space for carrying out the developmental activities as cited in the brief, the government seems to have marked these development zones inside the lakes, which by itself is an encroachment,” he notes.

“We did not want to disturb the bio-diversity of the lakes. Hence we proposed a model in which the bio-diversity of the lake can be retained by creating islands for the birds to come. We also avoided concrete structures. We also proposed a model that is for the community that can also be maintained by the community for long-term sustainability. However, the participants in the competition were not allowed to see the design proposals made by other firms. Only one firm was made to present at a given time (5 mins) that too over a Zoom call. Besides, the judges never raised any questions or sought any clarifications on the design proposal and this made us think if they were even interested in listening to the presentation,” says another architect who participated in the competition, adding that the lack of transparency is an issue as they did not know why they were not shortlisted or the criteria based on which the other firms were shortlisted.

How does community involvement help in restoring lakes in Chennai?

Chitlapakkam Lake in Chennai has no amusement park or guest house in it. But it has clean water restored in the lake. All due credits for this go to the community initiative. Sunil says that after the 2015 floods, they started analysing the root cause of the floods in their locality. The root cause turned out to be the lake in the locality that was neglected for many years. Chitlapakkam is located between two lakes – namely Sembakkam Lake on the east side and Chitlapakkam Lake on the west side. The connectivity between the lakes was affected as the canals and the walls of the lake shrunk over the years. Both lakes were also filled with sewage throughout the year. Chitlapakkam Lake also has a dump yard on the catchment areas of the lake.

“For the past three decades, Chitlapakkkam has had a vibrant Resident Welfare Associations. The community here are well-informed. After identifying the root causes, the residents conducted many campaigns and weekly activities in the lake. This drew a lot of attention towards the condition of the lake. The 2019 campaign for a massive clean-up in Chitlapakkam Lake turned out to be a major event as around 2,000 people turned up. This created pressure on the government to pay attention to the lake and allocated Rs 25 crore for reviving the lake,” he says.

Even after the government took up the restoration works, the community continues to monitor the progress of the work. “We clearly communicated that there should not be any plastic in the lake. The government did this first. We also demanded that the sewage should be removed completely from the lake. They also cleaned and desilted the lake. To arrest further sewage discharge inside the lake, the government also created a defecting peripheral drain. Now, it is perhaps the only lake in Chennai that has fresh water,” says Sunil. He adds that the template on how the community played a role to draw the government’s attention to restoring the lake should be replicated in other areas until bigger changes happen.

Even when the restoration works are still in progress, Sunil says that they have already started reaping the benefits. “A lot of birds can be found in the lake now. There are also a lot of fish. After all, we can breathe fresh air,” he says.

Not only has the eco-restoration of the Chitlapakkam Lake helped in improving the lifestyle of the residents but also helps them in saving a huge chunk of money spent on water tankers. “I used to spend at least Rs 4,000 a month on buying water tankers. There is a visible change in the groundwater recharge after the restoration of the lake and I have not spent a penny on water tankers over the past two years,” he adds.

Read more: Rethinking water body restoration in Chennai

Finding the balance in lake restoration

“It is not commercialisation versus restoration. It is about finding the balance between both. We will ensure the lakes are not used as a space for commercial exploitation. At the same time, we will also have to make sure there are adequate resources to further maintain the lakes and rejuvenate them at regular intervals. Unlike previous models where we float tenders to rejuvenate the lakes, we went ahead with a design competition as we needed inputs from a range of experts to find this balance and we are sure we will find this balance,” says Anshul.

Commenting on the issue of discrepancies in the maps, Anshul says that only a basic map was given to the participants who had entered the competition.

“Once the firms are finalised, the entire process of mapping and other such works will be carried out. WRD is the custodian of these lakes. All the developmental activities will be finalised only under their supervision. In no case, there will be an encroachment of the lakes,” he assures.

Chennai has lost a bulk of water bodies to encroachment and mismanagement. The impact of this has been felt acutely in recent years.

With substantial funding and a focused approach, Chennai’s lakes can mitigate much of the devastating effects of excess rain or drought. But a careful approach to ensure that the lake’s natural ecosystems are left undisturbed and not deprioritised for commercial gains is necessary.

With regard to the Chetpet lake, I think its main utility is as a green lung. Honestly, I think it is a brilliant idea to create walkways around lakes. Perhaps it does appear expensive to those who don’t use the place, but I have found several people who live in the surrounding under-resourced areas accessing the lake area for pleasure. It is important to understand the history of the lake. as stated by Mr. Harris Sultan, it does indeed not have inlets or outlets, but that is because it is not a natural water body. It is a former claypit, the clay from which helped build the Presidency College and the Madras High Court. That is why there is a Brick Kiln Road nearby. It is a practice in many parts of the world to fill former claypits with water for recreation; here it happens naturally, when rain water fills the pit. While it may not have the same ecological or water-security utility as say Poondi, Red Hills or Chembarambakkam, Chetpet lake is a pleasant place to meet, greet and work out. I think we need more places like Chetpet lake. I also feel sad that the maintenance of the lake is going down. In fact, some anti-social charitable humans have taken to feeding crows in the lake area. I have complained but no action has been taken against this very religious person. It has caused all the singing birds and small tits and sparrows to disappear. I fully support the views expressed here. just wanted to add my bit.