Picture this. Your monthly income falls from Rs 15,000 to zero. How does the state government, which is expected to mitigate the crisis leading to this situation, help you?

By announcing cash support of Rs 1000, 15 kg of rice, one kg of dal and one kg of edible oil. The help may not be really enough, but it’s some relief.

But no, wait, this feeling too proves to be fleeting, because the government wants you to be a part of a welfare board to avail the benefits. The board you didn’t even know existed.

This is the story of many an auto driver from Chennai. After the announcement of the lockdown triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in March, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Edappadi K Palaniswami promised aid for the state’s auto drivers, but only for those drivers who were registered with the Autorickshaw and Taxi Drivers’ Welfare Board under the Tamil Nadu Government.

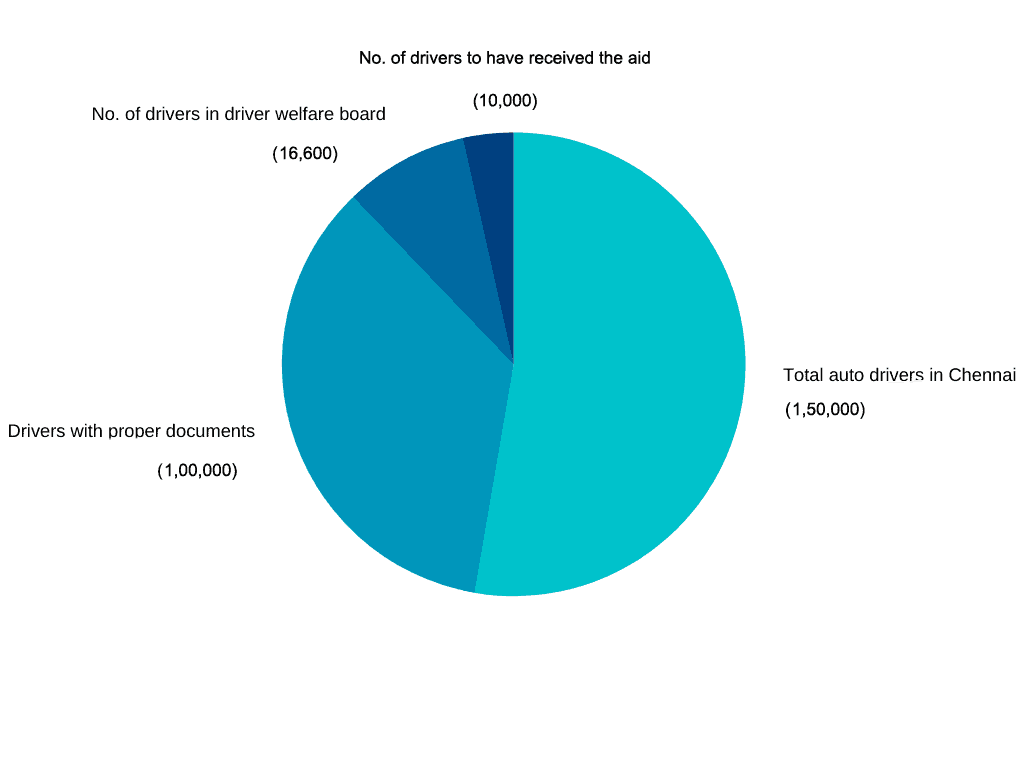

As it turns out, only 24,600 of the total 1 lakh authorised auto drivers in Chennai belong to the driver welfare board, according to data from the CITU-affiliated Tamil Nadu auto drivers’ association. Besides these 100,000, there are more than 50,000 members plying the auto without proper documents from the Regional Transport Office, suggests a 2017-based survey conducted by M Auto, a private auto-rickshaw service provider, as shared by Yasmeen Jawahar, CEO of the company.

Now, did all of the 24,600 members belonging to the welfare board avail the benefits? Sadly, no again. “Around 8000 drivers have not renewed their membership. And out of 16,600 members, not even 10,000 members availed the aid,” says M Chandran, Vice President, CITU.

Only 10 per cent of the auto drivers have received the Chief Minister’s special aid that was announced during lockdown 1.0 in March.

Lives caught in turmoil

Tears rolled down the cheeks of Rajesh Kannan as he talked to me from behind the wheels of his autorickshaw. Trying hard to swallow his sobs, Rajesh described in a trembling voice how the Coronavirus-induced lockdown forced him to draw upon his savings, which he had kept aside for his daughter’s education.

Ask him about the government assistance of Rs 1,000 for autorickshaw drivers, and his face grows paler. “I’m yet to get it,” he says in the same sad tone. He was not even aware of the welfare board and when I told him that he needed to be a member in order to be eligible for the relief, he was devastated.

“I did not renew my membership with the Board as it is a time-consuming procedure. One has to visit the office many times; I could not afford to skip work,” says Rajesh. This perhaps also explains why 8000 auto drivers had not renewed their membership, that makes them non-eligible for the relief.

Rajesh Kannan, an auto driver

The fact that a mere 16.6% of auto drivers belong to the board speaks volumes about the lapses in the system and lack of sensitisation.

The procedure to get membership from the Board is simple but involves multiple visits to the office. “All it requires is to get a form from the board, fill the address and other details and submit it to the official-in-charge. But the official was not in the office on both the occasions that I went to get it done,” said Sheik M, an auto driver, indicating the habitual laxity in these offices.

“It is a tough task to get a membership from the Board, as an individual driver, because the time foregone means loss of earnings. So associations such as CITU used to do the job by collecting forms from the drivers. But these days, the Board doesn’t take applications from the associations, a reason why 8000 drivers have not renewed their membership,” added S Balasubramaniam, active president, CITU.

Although an official from the welfare board said that they have conducted camps to get more people to enrol, he had no answer to justify the alarmingly poor strength in the board.

“Autos were allowed to ply for 13 days during the past three months. I could earn around Rs 1000, of which I spent Rs 800 on my medicines. We get customers only when public transport in the city is operational.”

Rajesh Kannan, an auto driver

How does the Board function?

The Board gets funds from multiple sources. But conversations with the community indicate that the funds are not put to good use. In other words, they rarely reach the actual beneficiary, an auto driver.

“The Board has funds worth crores, lying unused. Each auto driver spends Rs 265 to renew the license once in three years. An auto costs Rs 2.02 lakh today, of which Rs 39,000 goes as tax. A driver spends Rs 1400 for the road tax once in five years. One per cent of the tax in all these expenses goes to the welfare board,” explains Balasubramaniam.

For all the funds it possesses, the board allegedly does not even do enough to reach out to auto drivers. No information about the benefits it can provide or how to enrol can be found displayed prominently at any of the RTOs of Chennai.

How can things change?

Any scheme or aid that fails to reach out to the masses is a failure. The aid meant for the auto drivers benefitted only 10 per cent of the community. So what could be the solution?

“The aid amount should be increased to Rs 3000. Also, the government should distribute it to whoever has a batch license, as only a creamy layer of the community is registered with the welfare board,” says Yasmeen Jawahar, CEO, M Auto.

Not just the state government, auto-rickshaw ride offering services such as Ola and Uber should also reach out to the community during crisis situations as the present.

Kanikapathy (name changed), an auto driver working with Uber, told us that all the company did was provide disinfectants and sanitizers to maintain hygiene in the vehicles. “Besides that, there was no promise of any aid. The least any of these firms can do in the post-COVID world is to increase the profit percentage or commission for drivers to help us cover our losses,” says Kanikapathy.

It may be noted that Ola, too, did not make any promises for auto drivers.

However, in some positive news, M Auto which employs 30,000 auto drivers in the city has been pooling money to help the community. “I received financial assistance from M Auto to buy medicines for my mother. During the three months of the lockdown, M Auto has been helping a few auto drivers with dry ration and medicines,” says Tamizhan, an auto driver with M Auto.