In recent years, Bengaluru’s usually year-round pleasant weather has seen unusual scorching summers and intense rainfall and flooding during monsoons. What’s causing this, and is there anything we can do about it?

Responding to these questions in an interview with Citizen Matters is Dr J Srinivasan, Distinguished Scientist at the Divecha Centre for Climate Change, IISc. He has been associated with IISc since 1982 and had helped establish the Divecha Centre at the IISc in 2009. He was chairman of the Centre from 2009 to 2016.

A Ph D from Stanford University, Prof Srinivasan has been a lead author of the second and fourth IPCC reports on Climate Change. In 2019, he received the Lifetime Excellence Award from the Centre’s Ministry of Earth Sciences.

Excerpts from the interview:

Divecha Centre has done a lot of work on monsoon variability and on high temperatures/heat waves in India. What are the implications for Bengaluru?

A: Bengaluru will become much hotter, because of the increase in CO2 as well as the Urban Heat Island effect.

Predictions about the amount of future rainfall is difficult, but heavy rainfall events (greater than 100 mm/day) will increase, and cause urban flooding. Heavy rainfall, by its very nature, will be localised; it will occur in short spurts in small regions. For example, a few months ago when there was heavy rainfall at the airport, there was hardly any in Malleswaram.

Is the draft Karnataka State Action Plan on Climate Change sufficient to mitigate these impacts?

The action plan only considers increasing CO2. But when it comes to Bengaluru or smaller areas, many other factors like air pollution and land use change play a role too.

CO2 is important at the global level when you’re trying to reduce the global mean temperature. But Bengaluru is warming faster than the global mean temperature as the city has urbanised rapidly. So we have an urban heat island which is entirely because of putting up more buildings, which absorb and retain heat.

Read more: Bengaluru’s climate no longer cool. Here’s why

When you try to predict what Bengaluru’s climate will be like 30-40 years from now, you have to worry about urbanisation and land use change. The current action plan does not reflect the fact that at a smaller scale of a district and a city, there are many factors affecting climate other than CO2. The state is just churning out model outputs which are meant only for studying global climate change, not local climate.

India contributes barely 6% to global CO2 emissions. So what we do or don’t do doesn’t really matter. It matters only to convince other countries that we are also serious. Other countries like China, US, Europe, have to cooperate as they are contributing to 50% [of CO2], that affects us too. In contrast, air pollution is a local factor – air pollution in Bengaluru does not affect Delhi.

For example, if you have to understand what will be the climate in Davanagere 30 years from now, you have to understand how the urban area in Davanagere will grow. Then you have to worry about air pollution as it will also have an effect, and how land use is going to change. If you don’t put those factors into your model, you will get output that’s not realistic; it becomes a meaningless exercise. The model requires inputs on how your area will grow, how much green space you will retain. But all those numbers are not there.

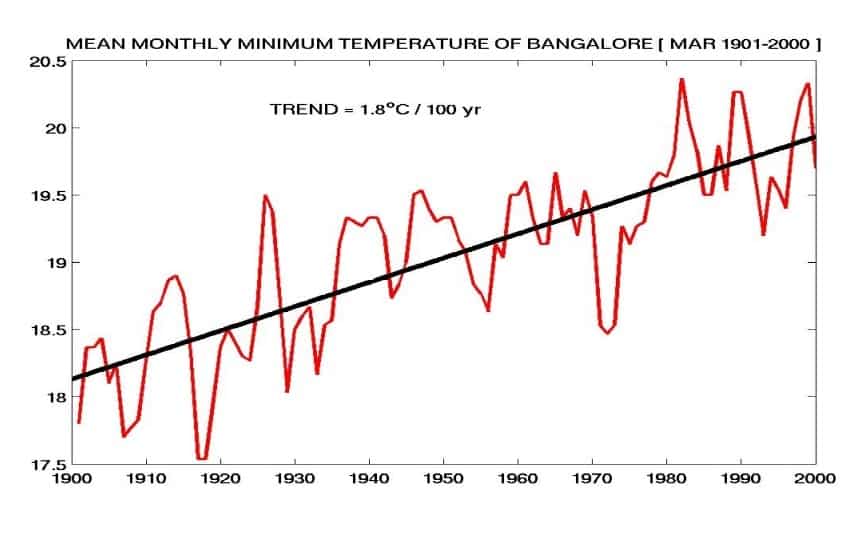

Is there data on the pace at which Bengaluru is warming?

For the month of March (which is the hottest in Bengaluru), night time temperature went up by two degrees in the last 100 years. Whereas the global mean temperature has gone up by one degree only.

Does air pollution per se cause warming?

There are three factors, CO2, land use and air pollution. There’s not much we can do about CO2 because it is controlled by global emissions.

Air pollution is a complicated factor. It has many components. One is sulphate aerosols which reflect sunlight and cool the ground; and the other is soot, which absorbs solar radiation and heats the atmosphere. So the impact of air pollution on temperature depends on the relative amounts of these two. In most of India, air pollution has so far cooled cities, not heated them. In Delhi at least, much of the pollutant is sulphate, which reflects radiation. In Bengaluru, I don’t know the exact situation, but it may not be that important compared to land use and CO2.

Is there enough data on factors like air pollution now?

There is a lot of data available on air pollution now – there are at least 10 sites in Bengaluru that measure air pollution; and there is a nice website run by Dr Sarath Guttikunda of urbanemissions.info which also predicts pollution levels. But this information has to be used. The data has to be collected, properly checked and used in a model. That has not been done.

I would like to know if state governments are taking the trouble to ask how our smaller towns are going to grow. Have they done any analysis of that? I don’t think so. Our urban areas start expanding before even our policy makers know about it. For example, has anybody predicted how Bengaluru would spread in the next 10 years and in which direction – will it spread towards the airport, towards Mysore or towards Whitefield?

Can Bengaluru’s Master Plan address this question of growth?

The Master Plan is a critical document. But we have not followed the Master Plan of Bengaluru made 30-40 years ago.

Today, because of satellite data, you can map how Bengaluru has changed over the last 30 years. Based on that, you should be able to predict what will happen in the next 10 years. That has not been done.

I think people have to take this issue more seriously and realise that this is about our own future. We have to first ask ourselves how the city changed in the last 30 years, whether it went according to the Master Plan. One has to understand how Bengaluru grew in the last 30 years, in which direction and why. For example, Bengaluru didn’t grow towards the north until the airport came. Second, development of real estate depends on water availability, it’s a critical parameter. So these things are important and should be looked into. The Master Plan is more a dream of how Bengaluru should develop, but reality is so much different from it.

Read more: Bengaluru’s changing rainfall patterns: expert points to climate change

So localised climate change effects can be mitigated once you have a proper action plan?

Not necessarily mitigate, but you know about it and you can plan for it. If a city grows rapidly, urban heat island effect will dominate. So you must learn how to develop a city with enough greenery, enough lakes, so that the heat island effect is controlled.

For example, in central Bengaluru, if they had allowed for enough open space, greenery and lakes, then the city would not have become this hot. So many small cities are going to grow now. So, based on the experience in Bengaluru, one has to make proper plans to ensure the heat island effect is minimised.

Are there ways to mitigate urban heat island effect in Bengaluru, given that there is extensive land use change already? Are there any predictions?

No, some of the change can’t be undone. For example, the additional one degree warming can’t be changed.

But you can learn from places like Singapore – even the big buildings there have more greenery (creepers) around it, which might cut down the amount of radiation absorbed. So some effects are reversible. In Bengaluru, for example, people put up concrete buildings and then it becomes too hot, so they put air conditioners. But ACs have a huge heat output. So ideally you should find alternative ways to cool a building; design the building such that you minimise the requirement for ACs. Such solutions have to be thought through. But whatever damage is done, I don’t think it’s going to be easy to undo it.

Further warming probably depends on how Bengaluru is growing further. The warming occurring already is due to the huge built-up area in the centre of the city. Suppose that goes on spreading outwards in the next 30-40 years, the centre will get even hotter. So it’s a question of how the built-up area will spread.

However, compared to any other city, Bengaluru is more green, it has a long tradition of being a green city. This is where citizens have to play a role – you have to make efforts to keep it green and make sure further development does not go the way it happened before. There’s a possibility of increasing greenery too, even in multistoried buildings, as Singapore has done. If you also have plants in the building, it will evaporate moisture, keeping the temperature down.

Read more: Lessons from Singapore on nurturing urban greenery in Bengaluru

About solutions to reduce CO2, how do you see the potential of rooftop solar panels in Bengaluru? Are they viable?

Bengaluru has about 180 cloudy days per year. So it is not as good as Rajasthan or North Karnataka which have more clear days. But, because the price of solar panels has gone down so much, it is still cost-effective in Bengaluru.

Even on cloudy days, you may get half the energy you get on a sunny day. So you have to design your panel, like sizing the panel slightly larger, such that you get enough energy.

Also, if you are staying in a single-storey building and you put up a solar panel, and a 10-storey building comes up next to you, you won’t get sunlight. So you have to look carefully at the situation in your area, whether there are taller buildings, trees, and so on. Also, in the case of a very tall apartment complex, the area available for rooftop installation will not be sufficient to generate energy for all the households there. But complexes that have enough open area can put up panels in those spaces instead of the rooftop.

Big companies that install solar panels usually have the expertise and give estimates of how much energy can be generated from a rooftop panel installation.

One advantage of rooftop panels is that they cut down the heat load in the building. So on hot days like in March, if you have solar panels on the roof, your room will be cooler. In the long-term interest of the country, the government has to give incentives for rooftop solar for houses.

Currently, BESCOM has the net metering scheme (where consumers can use solar energy from their panels and supply excess power to the grid). What other incentives can the government give?

About 30-40 years back, there was some incentive for putting up solar systems for heating water. The biggest domestic load in Bengaluru is in early morning, when geysers are switched on. It used to cause power cuts in the 70s and 80s. If you have a solar heating system on the rooftop, that load goes down substantially. Because the central government has a huge plan for rooftop solar, some such incentive should be provided now.

But first they should make rooftop solar a requirement for every industry and every commercial establishment. Because the power tariff for domestic and commercial are very different, commercial establishments will find it economically viable. Also, solar panels with storage are less expensive than a diesel generator (DG) set. Traditionally, almost all industries and commercial establishments have DG sets, but today they cost Rs 10-12 per unit [of power generated].

India has made a commitment to generate [renewable energy capacity of] 450 GW by 2030. In the initial phase we have got 100 GW of renewable energy, which is remarkable. But as we go along, there may be some constraints on where you can find land to put up solar panels; so rooftop is a very attractive option for both industry and domestic consumers. But if it’s not picking up, then one has to look at why, and provide suitable incentive for a short period.

Solar panels on land is tough in Bengaluru, as land is very expensive. But there are any number of other options. For example, panels can be put right over a highway and an electric vehicle charging station installed next to it. Other countries are doing this. As a matter of fact it’s going to come [here], because as we move to electric vehicles, we need charging stations which should ideally be solar-powered.

Is the transition to electric vehicles happening at the required pace in Bengaluru?

Companies that make fossil fuel vehicles are a powerful lobby, so they are not going to easily allow electric vehicles [sector] to grow rapidly. I’m happy that the government has given incentives for electric two-wheelers, because two-wheelers are the most polluting vehicles on the road – not only do they generate pollution on combustion, they also generate unburned hydrocarbons which are extremely dangerous as they cause all kinds of cancers. If you look at central Bengaluru, the major pollution is coming from diesel buses, auto rickshaws and two-wheelers. So two-wheelers and auto rickshaws going electric is the best way, and I expect that to happen in the next few years.

I think, in the case of four-wheelers, the transition may take another 10-20 years because a lot of money has been invested in petrol and diesel vehicles. The latest budget gives a major incentive [for electric vehicles]. How it is going to be implemented is very important.

[In the next part of this series, we speak to Dr Chandan Banerjee, hydrologist and Associate Director at the Water Solution Lab Bengaluru under the Divecha Centre for Climate Change, to know about the lab’s work to try and solve Bengaluru’s water woes.]