Chennai can be called a groundwater city. Almost 60% of our daily needs is met from Chennai’s groundwater sources, both at the macro and micro levels put together. This groundwater source can be sustained only by harvesting rain.

Rain can be harvested in only two ways:

- Collecting rainwater in masonry/plastic tank for immediate use and/or

- Putting rainwater into the soil which is known as recharge.

Chennai’s groundwater bank

Groundwater should be thought of as a bank. Extraction of groundwater should be compared to withdrawing money from the bank and recharge to be depositing money in the bank.

Recharge is of two types: a) Natural and (b) Artificial.

What is happening in rural areas is natural, by virtue of large tracts of area remaining unpaved. In addition, natural recharge is also happening all along the entire coast in India having sandy soil. In Chennai this is true in areas like Besant Nagar, Valmiki Nagar, Mahabalipuram and beyond.

On the other hand, artificial recharge is relevant mostly in urban areas, where it is all built up.

Read more: Jolted by water shortage, Chitlapakkam RWA takes up roadside rainwater harvesting

Why should groundwater be recharged?

Groundwater should be recharged to sustain and improve the quality and exploitable quantity of groundwater wherever it is good and improve the quality and quantity of groundwater wherever it is not so good. If recharge is not resorted to, the situation will go from bad to worse.

Recharge is relevant everywhere except in places where the soil is rocky and where the groundwater level is high throughout the year. There are a few criteria which would make recharge extremely relevant.

- In places where the quality and exploitable quantity of groundwater is good

- Where the soil is reasonably permeable

- Where the pre-monsoon (and at times even post-monsoon) groundwater levels are not high

Soil can be broadly classified into five different types: a) sandy (b) silty (c) clayey (d) gravelly and (e) rocky. Silt is a mixture of sand and clay. While (a), (b) and (d) are permeable soil (c) is not so very permeable and (e ) is totally impermeable.

Grouping Chennai’s groundwater

Chennai city (or for that matter any city) can be broadly grouped into four kinds of areas. This classification will vary in different years.

- Areas where the soil is permeable and where the pre-monsoon groundwater level is low.

- Areas where the soil is permeable and where the pre-monsoon groundwater level is high (this is quite rare).

- Areas where the soil is not permeable (extremely clayey or rocky) and where the pre-monsoon groundwater level is low.

- Areas where the soil is not permeable (extremely clayey or rocky) and where the pre-monsoon groundwater level is high.

The first kind is the most suitable one for recharge and there can be no reason/justification for not doing recharge.

Areas of Chennai which fall under these four groups will have to be identified, understood and documented and follow up action taken accordingly.

Read more: Groundwater resources: Why central Chennai has more than other regions

How can groundwater be recharged?

For collecting rainwater in a masonry/plastic tank for immediate use, rain falling on rooftops alone is preferred, whereas for the second option, rain falling on both rooftops as well as the driveway are good. Even the urban runoff can be used for recharge.

Recharge should be carried out through recharge wells, which are 15 feet deep and are made using cement rings readily available in the market.

The diameter of these RCWs varies from 3 to 6 feet depending on the catchment area and these need to be left empty and covered with a thick RCC cover.

At the micro level, each resident should ensure that every drop of rain falling within his/her premises is harvested either as collection for immediate use or recharge.

This in turn implies that rain falling on both rooftops as well as the driveway is harvested. The latter invariably goes to the street through the gate(s) in every premises. This will have to intercepted near the gate(s) and led into recharge wells.

Rainfall in public spaces in Chennai

At the macro level, rain falling on public spaces is presently channelised to stormwater drains and discharged into the sea in several areas of Chennai. This is being widely promoted by the GCC as a flood mitigation measure. This should not be thought of as the only flood mitigation measure.

Even recharging is. The first step should be to make as much use of recharge and then only consider the option of discharging large quantity of rainwater into the sea year after year.

Read more: How to start harvesting rainwater at your home in Chennai

Benefits of recharge: (a) Improvement in quality and quantity of groundwater, which helps to sustain the groundwater source (b) Reduction in the occurrence of floods since what is not harvested floods the area.

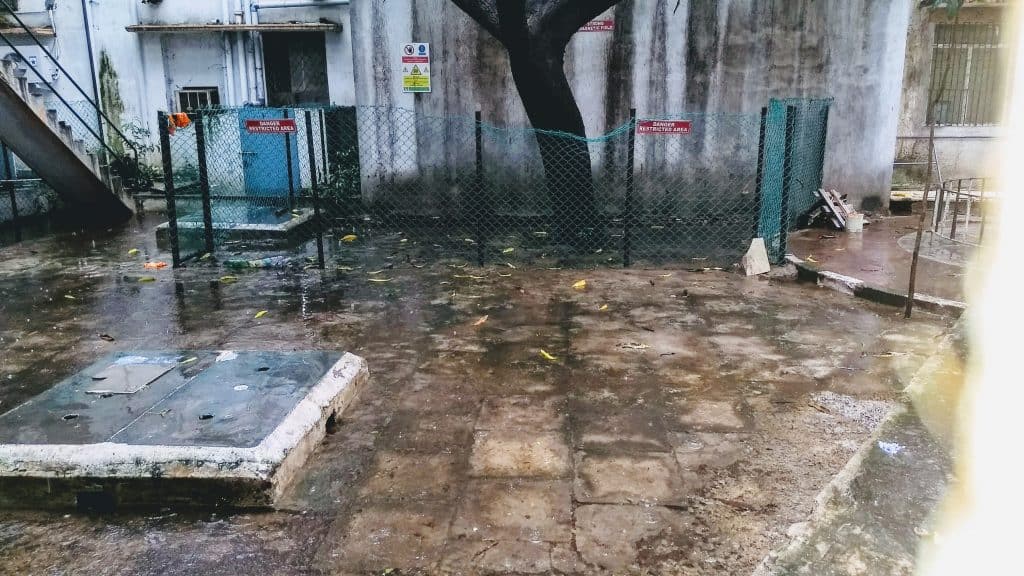

In places where waterlogging, inundation or stagnation occurs on the sides of roads, recharge wells can be dug and covered with thick perforated RCC lids so that stagnant water can percolate into the soil.

In areas where the soil is likely to be sandy like Besant Nagar, Valmiki Nagar etc. leaving two to three feet of unpaved area on both sides of the road is all that is required for recharge to happen. There is no need for recharge wells also.

Lastly, we should realise that floods and droughts are better prevented than cured. Recharging Chennai’s groundwater will help to prevent this to a large extent.

[This story was first published on Madras Musings. It has been republished with permission. The original article can be found here.]