Even before summer had set in officially, the two borewells at S Velu’s residence in Selaiyur turned dry in April. In search of water, he dug another borewell as deep as 600 feet, but that too failed to yield any water. Velu is now at the mercy of water tankers and municipal water supply and uses water sparingly. Although Chennai’s water situation is not as alarming or critical as it was in 2019, groundwater resources in several pockets of the city are reportedly drying up. As a result, besides using water supplied by the Metrowater agency, many households and industries in Chennai are now tapping the available surface water resources to the fullest extent to meet their needs.

Groundwater resources have always played a vital role in meeting the additional demand by households and industries. However, indiscriminate utilisation of groundwater has also led to a rapid fall in the water table in the city.

A report on groundwater resources of Chennai states that till 1970, most parts of the city extracted groundwater through open wells, by a mode of extraction known as hand bailing. The tradition of boreholes was introduced in the early 70s in the city, leading to the practice of extraction we see today, which is also called groundwater mining. As population has increased, so has the depth of borewells, many of which now go down 600-700 feet below the ground.

But is that the only reason that certain parts of the city are finding underground sources exhausted? Is that why their borewells are failing? Why, then, are some parts worse off than others?

While groundwater mining and over-exploitation holds the key to such shortage, one must also try to understand what lies beneath the city. One must also understand that existing reserves of groundwater are not uniform across the city, and are dependent upon ‘hydrogeological’ patterns. Extraction should also be guided by that.

“Hydrogeology is the study of groundwater in relation to sub-surface of earth which is made up of rocks,” says L Elango, Professor and Head – Department of Geology, Anna University. Broadly, we can categorise the city into coastal Chennai, South Chennai, North Chennai and West Chennai to get an overview of the city’s natural groundwater levels.

Read more: Chennai will be a water abundant city in five years: Metro Water official

Coastal Chennai

The stretch beginning from Ennore to Sholinganallur along the sea has a coastal aquifer. “Aquifers are the bodies of rock/sand/unconsolidated sediment under the surface of the land we tread on, which can store and release water. The depth of aquifers and the yield varies from one locality to another naturally,” explains Elango.

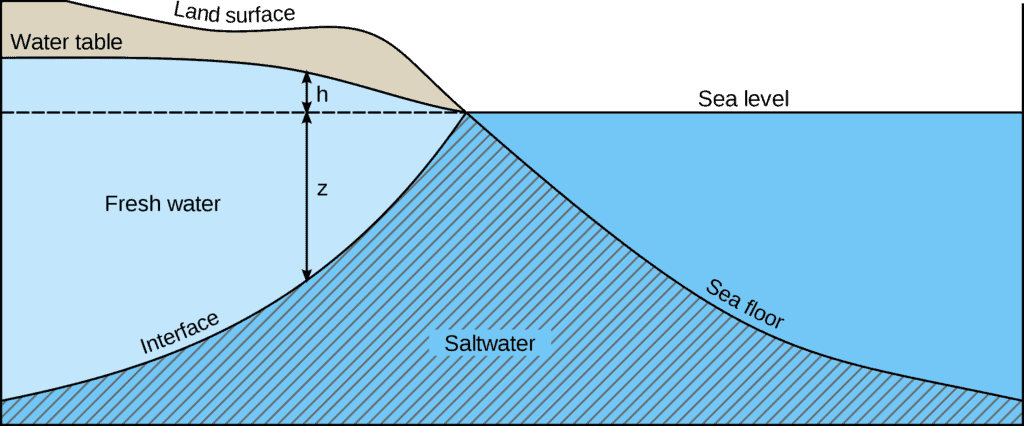

In coastal aquifers, fresh water and saltwater zones are in a fragile balance. The saltwater zone is brackish and the boundary between the salt water and fresh water zone is indistinct.

“The coastal aquifer is unique and complex in our city, as we have to balance water extraction with the actual natural recharge. When the extraction goes beyond certain limits, seawater intrusion takes place,” says J Saravanan, a hydrogeologist and water expert.

When seawater intrusion takes place, saltwater moves up towards the land. This makes an impact on the quality of the groundwater that we draw. The thumb rule in coastal localities is that extraction should happen at a pace that maintains the freshwater-saltwater balance. The permitted TDS (Total Dissolved Solids) value in freshwater can range from 500 to 1000/1500 mg per litre. In saline water, the TDS value goes up to 35,000 to 45,000 mg per litre.

Then how can residents ensure they do not dig deeper and upset that balance? This can be done by checking the TDS value for every foot people go down and constantly monitoring levels with a handheld TDS testing device.

“In principle, salt water is 40 times denser than freshwater. Even to push salt water down by one feet, freshwater has to go up by 40 ft, which means it is extremely difficult to push back the saline water,” adds Saravanan.

Therefore, groundwater in these coastal areas is often not great either in terms of quality and quantity. Saravanan calls for implementation of an extensive rainwater harvesting (RWH) system in these areas. “Residential RWH alone will not suffice to meet the needs. Harvesting systems should be implemented along roadways, in temple ponds and water bodies in coastal zones,” he says.

Read more: Why residents in northern parts of Chennai throw away pots of water every week

Central Chennai

Two rivers – Adyar and Cooum – flow through the central part of Chennai. Hence, in this part of the city, one finds alluvial soil deposits up to a significant depth, below which hard rocks occur.

The alluvium zone created by the Adyar river deposits is between 10 and 20 metre in depth and the granularity of this alluvium varies from one location to the other. Cooum alluvium varies in depth from 10 metre to 28 metre and is more granular in the Kilpauk – Perambur area.

“The alluvial zone is a good region to tap water, as the porosity of alluvium makes it particularly suitable for storing water. If there is a deposit of 100 cubic ft of alluvium, this can absorb water up to 25 cubic ft,” states Saravanan.

South Chennai

Alandur, Pallavaram, Tambaram, Guindy and Velachery are some of the localities that make up South Chennai. These localities have rocky terrain, geologically classified as hard rock areas. The storage capacity of hard rock aquifers is much less compared to alluvial aquifers.

Hard rock zones have only two kinds of aquifers: weathered aquifers and fractures. “For instance, in Tambaram the top zone (up to 5 or 10 metres) is made up of soil, followed by a weathered aquifer, formed by disintegrated rocks. The aquifer in this zone is called a weathered aquifer. In a fracture acquifer, the top zone is followed by massive rocks,” explains Elango.

In the first type, “the weathered zone (made of soft, weathered rocks) appears below the topsoil zone, its depth varying from 6 to 15 metres depending on the locality. Places having weathered zones are ideal for hosting open wells that get immediately recharged after the monsoon,” says Dr B Umapathi, retired scientist from the Central Groundwater Board.

Water can seep through and reach the fractured zone only when the fractures are connected with weathered rocks,. “When we dig a borewell in a hard rock zone, we are able to find water only if it encounters fractures that are connected with weathered rocks (called joints). In many places, the joints may be absent due to which borewells fail,” Umapathi adds.

In hard rock aquifers, the water table should be maintained at a shallow level. Once the water table falls further down to the hard rock area, the capacity to store and release water falls significantly, due to which borewells do not yield much.

West Chennai

Unlike Central Chennai, in the western part of Chennai, there is a limited amount of alluvium under the topsoil, followed by clay. Areas like Valasaravakkam, Virugambakkam, Anna Nagar and Porur have clayey soil. The groundwater found in these areas is rich in iron, making it unfit for domestic consumption.

“The quality and quantity of water we draw in west Chennai is tricky. For instance, in Valasaravakkam, water up to 0-10 metre is of good quality, while at 10-30 metres it is rich in iron, making it unpotable. Below 30 metres, the water turns saline. However, if we go to Porur, even water below 30 metres is found to be of good quality. A borewell drilled in Valasaravakkam at 250 feet yields saline water whereas in Porur we get fresh water from the same depth,” explains Saravanan.

North Chennai

North Chennai rests on sedimentary rock, with sandstone and sand or shale forming the layers beneath the topsoil, making it conducive for good groundwater yield.

The hydrogeology of this area is impacted by the flow of the three lifelines of the city — Adyar, Cooum and Kosasthalaiyar rivers. These originated several thousand years ago and have changed their tracks many a time over these centuries. As a result, the underground deposits and groundwater capacity in the area have also changed.

Along with water, the rivers also deposit along their course other particles such as soil, soft rocks and the likes. Umapathi states that the change in course has particularly affected the northern parts of the city as porous materials that are heavy in nature are deposited upstream in the northern part of the city. The river carries finer particles down to the central part of Chennai, where they are deposited in the form of alluvium.

A complex subject presented in the most simple way!!!

Great

Very thoughtful piece of writing

Throwing more light on the pathetic water management

This is high time for government to take corrective steps

Proper and well intended Rain water harvesting will ease this problem. The excess run off can be channelised to these wells which will recharge the ground and yields water during scare days. More over percolation tanks can be revived and the storm waters can be diverted to such tanks or ponds for effective recharge.

Very informative. In addition to RWH, at least 90% of sewage water must be treated and that must be used for recharging ground water table. Not a drop of raw sewage water must be allowed to enter into the ponds / lakes. This must also be done on war footing.

Thanks.

Muthuswami