The movie Contagion’s grim visuals of uncollected garbage lining deserted streets haunts me, as I consume media reports about increasing COVID-19 cases. The lesson from 1918 flu pandemic was a mirror image of the movie Contagion as the flu did not differentiate between class. Waste Management and people who work in and with waste are extremely vulnerable, so how do we draw up a framework to fortify systems, sensitise citizens and protect frontline workers?

Challenges are varied depending on generators of waste, type and quantity of waste, destinations, processes and worker safety.

Challenge #1: Where does the waste originate?

The first challenge is to re-define the classification of waste generators during COVID-19. One must look at the general population including slums and informal settlements, people in home quarantines – both from people with mild symptoms and asymptomatic – waste from places post contact tracing, people in quarantine camps at the borders and other areas, COVID clusters, people in hospitals, general hospitals, diagnostic labs and street waste. But this classification only focuses on known infected cases and the non-affected population’s singular focus on protecting themselves.

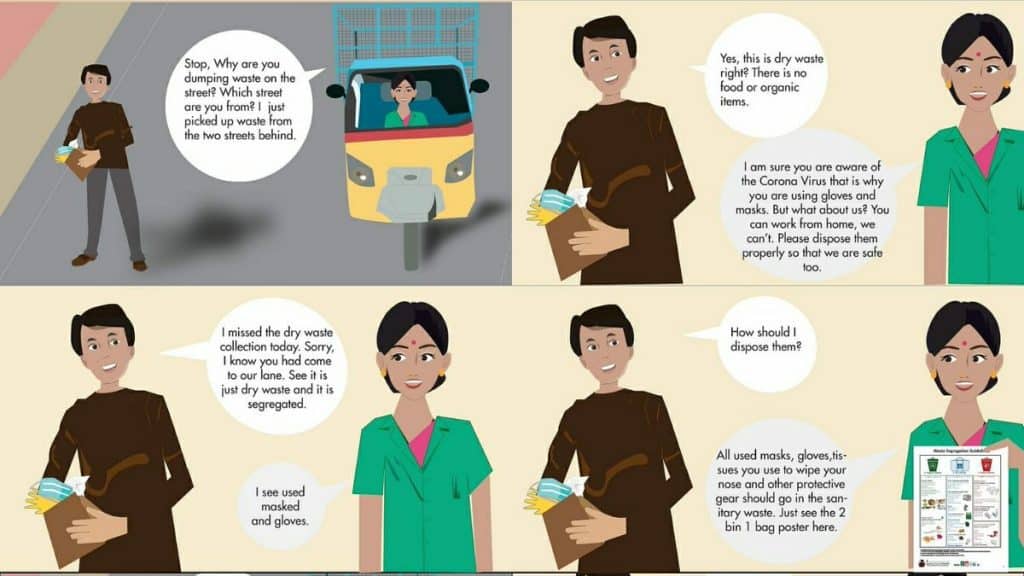

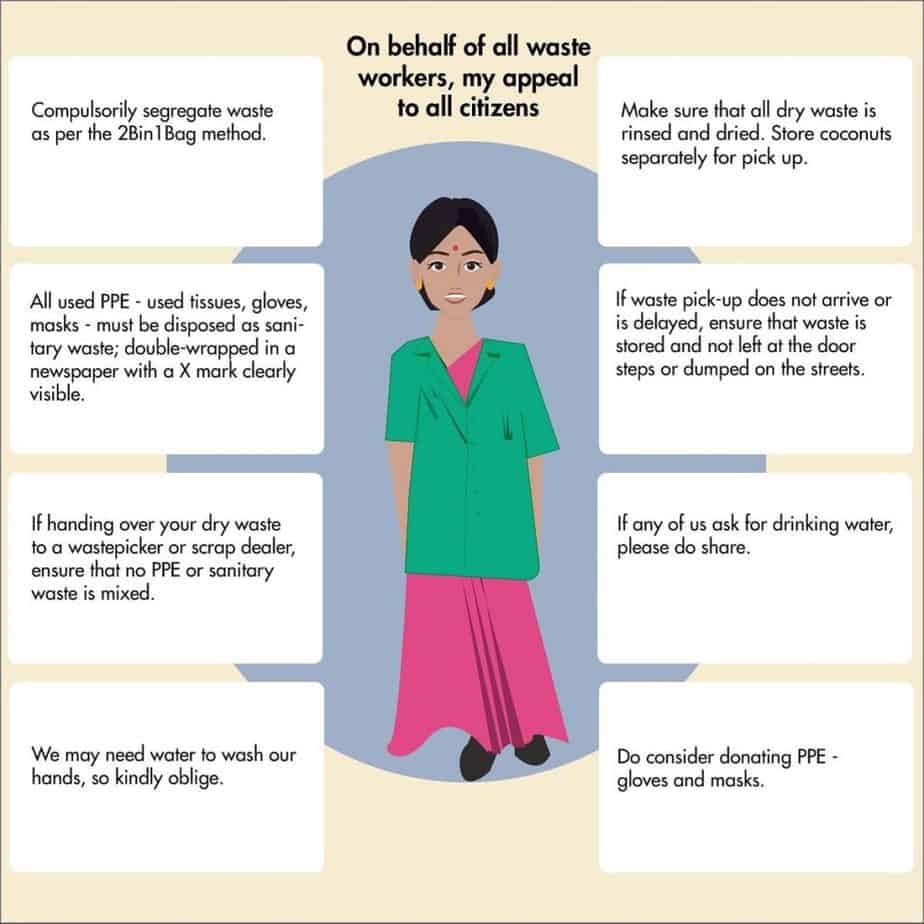

Shekar Prabhakar, Co-founder of Hasiru Dala Innovation, says, “I suggest a flip for the non-affected population. They must consider themselves as asymptomatic carriers of the virus and must give a serious thought on what they are disposing or what is going out of their homes. Masks, gloves, hand/face tissues should be wrapped in a newspaper with a X prominently displayed and collected in garbage bags, placed in a separate container clearly kept aside and handed over to the waste collector only at the time of collection.”

“Now is the time to ensure unified colour-coded system”

Myriam Shankar, Co-founder, TACIT, agrees with Prabhakar, “Now is the time to rigorously implement a system where we have a unified colour-coded bin system. Waste should not be touched by anybody, especially at the waste worker level. Perhaps, now would be a good time to expand the current three bins into more categories, given that the coronavirus stays on different surfaces for different periods of time. It is unfair to expect waste workers to segregate or even be dumped in the landfills/quarries.”

Street waste is another huge challenge in itself – not only is it mixed, it does pose a huge risk, if there is waste that has been contaminated. Shankar adds, “Hypothetically, I am playing out a scenario, if a COVID-19 carrier throws a wrapper on the ground, say at a playground, and a child comes in contact accidentally, and carries it home, embraces his mother, etc then the entire chain is affected. Yes, I understand that this is not possible now in a lockdown, but how long will the lockdown continue? And this could also be a waste worker who touches it. The prospects are scary. We need to be aware and cautious than sorry.”

Challenge #2: Rise in biomedical waste

The second challenge is the rise in biomedical waste from hospitals, along with an increase in disposal of personal protective equipment (PPE) by the general public. As witnessed by China, in Wuhan, where the novel coronavirus first emerged, the biomedical waste being generated was so high that the government had to deploy mobile waste treatment facilities and construct a new medical waste treatment plant.

According to Myriam, the installed capacity for biomedical waste is totally inadequate. She says, “With the amount of PPE disposed of, Bengaluru can only manage less than a third properly as per the law. Imagine the increased outflow, it is extremely disturbing.”

Equally disturbing, is the lax and ‘I don’t care attitude’ towards segregation of waste at the household level, leading to an increase in mixed waste. Mixed waste, in times like these, compromise destinations and put public health at risk.

Prabhakar also believes that since the coronavirus is known to survive on certain materials like cardboard, plastics, etc, all dry waste must be stored for as long as possible in homes. He says, “The primary responsibility of thinking about waste and how to manage waste has to be shifted up the chain to the waste generator (through consumption) and the brands (through products whose consumption creates waste). It is only then downstream waste management can be optimised for material recovery with least harmful effects to waste workers.”

Challenge #3: Mapping households to waste service providers

The third urgent challenge is inter-departmental coordination to map households and waste services, based on generators mentioned above. This needs to be digitally mapped.

Challenge #4: Waste worker awareness and safety

The fourth challenge is around worker awareness and safety. The waste workers need to be trained on how to handle waste, new instructions must be provided on how to handle waste from specific generators who have been in home quarantine, and to handle the influx of PPE disposed of from households.

“Waste workers need clear instructions on how to handle waste from those in home quarantine”

The government must distribute PPE to all workers, including instructions on how to clean and when to dispose and where to seek supplies when the PPE is torn. At a special sitting of the Karnataka High Court on March 30, the Court directed the State to provide safety equipment to every sanitation worker in Karnataka and provide breakfast and transport facilities during the lockdown. Can the Karnataka Essential Services Maintenance Act, 2015, be used to protect waste workers – both registered and informal?

There is need for a separate vehicle to collect these waste based on types of generators. But the problem arises when the worker has to also collect from the general population, along with those quarantined or asymptomatic. What happens when the garbage falls from a torn bag, how do the workers handle that? Should the waste from these households be double-bagged in plastic, which is banned in Karnataka, or should it be wrapped in newspaper?

Challenge #5: Where does the waste go?

The fifth challenge are the waste destinations – guidelines, processes, data and penalty. What are the guidelines on handling tissues or gloves mixed with dry waste? Should the entire lot be treated as contaminated, even if one of the houses has an asymptomatic person? This is in relation to the staying power of the virus on different surfaces.

What about the biomedical facilities themselves? How equipped are they to handle the waste? Has there been any preparedness, audit to check the capacity? How can data be tracked and compared? What are the provisions for dumping of COVID waste?

When downstream waste processing plants are shut

The sixth challenge is reverse supply chain logistics. While waste is being collected, it only gets accumulated in destinations, as the rest of the downstream recycling and processing operations are shut down. What are the solutions, then? Can the entire value chain from collection, recovery, recycling be treated as essential services?

Laws and legal frameworks

Let’s go back in time and look at the different legal frameworks.

‘The Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897’, to control communicable diseases, is limited in its approach as it is only regulatory in nature and is silent on many areas including the implementation of response measures. The act completely excludes people and the human rights angle and is oblivious to issues of waste.

The Disaster Management Act, 2005, is much broader in its focus, but leaves much to be interpreted if a pandemic would be classified as a natural disaster. It does make a mention for the need for debris removal and the need for preparing a disaster management plan including a disaster rescue plan, which is more relevant to our context.

The Karnataka Epidemic Diseases, COVID19 Regulations 2020, notified in the gazette under the Epidemic Diseases Act, to prevent the outbreak and spread of COVID-19, in force for one year from 11th March 2020, makes no mention of waste management.

On 18th March 2020, the Central Pollution Control Board issued the ‘Guidelines for Handling, Treatment and Disposal of Waste Generated during Treatment/Diagnosis/Quarantine of COVID-19 Patients’. The covering letter specified that in addition to these guidelines, existing Solid Waste Management Rules 2016 and Biomedical Waste Management Rules 2016 must be practiced.

The guidelines provide a series of steps for handling and safe disposal of waste from different quarters. It recommends double-bagging of waste from COVID-19 wards including labelling bags/containers as COVID-19 Waste, recording generation of waste, use of separate trolleys and disinfectant methods.

For quarantine camps/home care, the guidelines recommend that routine waste is treated as part of SWM Rules 2016, and only biomedical waste be collected separately in a yellow bag and handed over to authorised waste collectors. It however does not specifically address asymptomatic people or those with mild symptoms, assuming that positive cases will be hospitalised.

One positive aspect of the guideline is under the duties of the State Pollution Control Board: to maintain all records of COVID-19 treatment wards, quarantine centres and homes, and specify the need for collection of biomedical waste from locations not under regular healthcare facilities.

What should Karnataka do?

We need multi-objective, multi-layered, multi-period/duration, multi-actor, multi-communication, approach to handling waste generated during COVID-19 outbreak.

Malini Parmar, Cofounder, Stone Soup, says, “The first principle of waste warriors is to eliminate it.” She explains how the Chennai floods meant waste could not be collected, “There are a lot of things people in disaster zones do differently and holding on to our waste during these times should be one of them.”She says if waste is being collected, all should be considered as household hazardous and treated as such. The way to avoid that high cost, would be reduce waste generation, an option that needs political will, “Compost, eliminate single use disposable cutlery, packaging, choose sustainable hygiene products, (then) you can hold your waste for months! Rescue teams should start disseminating information on Do It Yourself (DIY) techniques for these along with relief!”

As a first step, we need a Disaster Waste Management Contingency Plan, with all necessary orders, guidelines and details. As Malini says, “A disaster management plan should be made beforehand and tweaked, based on specific situations. We should not get into a mad scramble to create documents after the disaster.”

Click here to view detailed guidelines.