In part 1 of this story, we saw the economic impact on informal waste workers’ livelihood and the entire informal recycling sector due to the lockdown. We now see what policy changes have been proposed in the waste recycling sector and what action Bengaluru has taken on the ground.

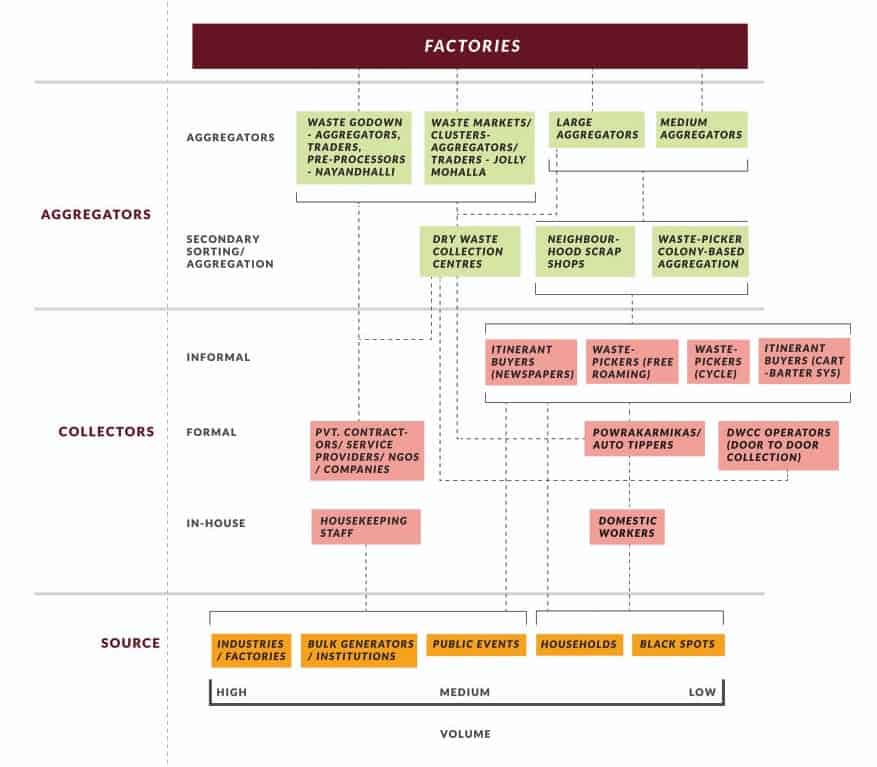

Let’s start with understanding the informal waste recycling sector — this Indian ecosystem is quite unique . A formal study on Recycling Hubs showed Bengaluru’s informal recycling value chains crisscross the formal and informal segments of the economy at many different levels.

While in recent years, waste pickers have been recognised in policy discourses consistently, the pace of implementation is quite slow

Sustainable livelihoods in the informal waste recycling sector

The Swachh Bharat Mission Manual on Municipal Solid Waste Management – 2016, from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), speaks about the need to create enabling conditions and presents options for actionising an inclusive approach. It recognises informal waste workers (not limited to waste pickers, but the entire informal recycling value chain), and highlights job creation possibilities through recycling, acknowledging them as partners, and need for access to social security, loans, tax exemptions, reserving land for decentralised processing, offering service contracts and skill development. (More details in the 2019 study: A Mirage- Assessment of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and SWM Rules 2016: Waste Pickers Perspective Across India)

The MoHUA document titled “Empowering marginalized groups – Convergence between SBM and DAY-NULM”, recognising the role of the informal sector in sanitation and waste management services across the value chain, outlines operational structures and indicative financials to enable sustainable livelihoods, and recommends social mobilisation and institution building to achieve i

Bengaluru – pioneer in SWM practices and worker empowerment

First let’s look at the bright side. Bengaluru, to its credit, has had many firsts, with some initiatives spearheaded by citizens, non-governmental organisations, and some supported through the judiciary.

Recognition of waste pickers and issuance of Occupational ID cards

BBMP has the unique distinction of being the first urban local body to issue Occupational Identity cards for waste pickers in the year 2011. The card had a 10-year validity and in the first phase around 4,125 waste pickers were registered. As of 2018, around 7,000 waste pickers were registered in total.

Three-way segregation and setting up Dry Waste Collection Centres

Bengaluru was also one of the first cities to have experimented with three-way segregation and a semblance of a dry waste collection centre model as early as the beginning of the nineties, with Mythri Sarva Seva Samithi Trust (MSSS)’s “Waste Wise project”, for 300 households in Jayanagar, where residents were given bamboo baskets to hold dry waste and were asked to commit to three-way segregation.

The evolution of DWCCs began in 2003 through the Center for Environment Education’s project titled ‘Environment Improvement Programme for HSR Layout – Implementation of SWM Activities’, which mirrored the Waste Wise project, but on a larger scale covering 3,000 households in all the seven sectors; wet waste was sent to Karnataka Compost Development Corporation (KCDC), for composting. A separate shed in Sector 1 was used for secondary segregation of dry waste. Thus began the evolution of dry waste collection centers.

DWCCs in the city gained full momentum post the Lok Adalat intervention in 2010-2011 and subsequently the High Court direction from 2012 onwards.

Read More: Managing waste in Chennai: The way ahead

Memorandum of Understanding with waste pickers

Bengaluru became the first city to sign a memorandum of understanding with waste pickers. In 2017, taking the rules into true action and spirit, BBMP allowed DWCCs to collect door-to-door dry waste. The BBMP Solid Waste Management Bylaws – June 2020 clearly emphasises that integration of informal waste collectors – identity cards, involvement in dry waste management – is an essential facet of SWM.

Institutionalising policy

The Karnataka State Urban Solid Waste Management Policy 2020 lists the need to ensure environmental, social, and safety linked safeguards for personnel (formal and informal) such as pourakarmikas and informal waste workers involved in waste collection and handling. The document also states the need to promote and protect safe and decent livelihoods of waste pickers, waste collectors, and aggregators.

COVID Relief Package for waste workers

The State Government announced the COVID Relief Package and as part of that, an amount of Rs. 2000 was allocated to unorganised sector workers. This scheme is accessible only to waste pickers registered with the Labour Department.

So where are the problem areas?

While Bengaluru has come a long way, some key challenges remain.

Registration of Waste pickers and other informal waste workers

The BBMP started registration in 2011, however, the numbers are abysmally low, with only 7,000 cards being issued. The 10-year validity of the cards will expire in 2022, and there has been no communication regarding the same. Nalini Shekar, Co-founder, Hasiru Dala, states that “Registration should be a continuous process and that is what was mentioned in the first circular issued by the BBMP. However, the registration of waste pickers has been abruptly stopped and there is no clear direction on the process.”

Problems at DWCC – infrastructure, budget, arson, payments

The BBMP Budget has earmarked Rs. 999 crore for Solid Waste Management of the city. Of this DWCCs will receive only a mere 5 crores for upgradation. The infrastructure of the DWCCs despite their contributions in retrieving materials and the quantum of waste coming in has not kept pace.

With initial designs being faulty, the situation has been alarming, with cramped spaces, leaking roofs, faulty construction of facilities, poor lighting and ventilation, no access to proper toilet and water facilities, waterlogging in certain DWCCs, as the loading area is not surfaced, in addition to problems of pests and rodents.

The recent spate of fires at the best-performing DWCCs at Wards 194, 177, 165, 181 and 86 from January to February 2021 is not just concerning, but distressing, pegging the damage at the lowest estimate to Rs. 53 lakhs which included removal of old existing fibre roof sheets, replacing of roofing, disposing debris, and laying of tin roof sheets, including labour charges, bonding material, painting, replacement of existing shutter, repairing windows, ventilators, doors and fitting for toilets, electricity fitting and wiring, cleaning charges, and repairs to existing machines. And this did not include damages to materials burnt and loss of pay to the workers and the operators.

Payment delays continue to hamper DWCC operations, with a total outstanding amount from BBMP of more than Rs. 4.35 crores for 42 centers (as of June 2021).. The process of transferring files across to processing payments needs a complete overhaul. Initially brushed aside as technical glitches and teething issues, these problems continue unabated and cannot be allowed to do so, especially with payments pending for over six months up to three years, with no explanation and accountability from the BBMP.

Poor visibility of other informal waste workers

The COVID-19 essential services of waste collection showed that the formal system completely depends on the informal waste sector for its aggregation and processing, says Nalini Sekar. She adds, “The informal waste workers and sector has so many nuances that most don’t understand. For instance, if we see the official figures of waste collected, processed/dumped is over 5,500 tonnes as per the BBMP. But a 2018 study on the informal waste recycling hubs revealed that approximately 4,000 tons of plastic (itself) is traded every day in the city. And this is true for other materials too.” The irony is that the informal waste workers above the value chain have no visibility despite doing so much work.

Accessing relief packages

Many waste pickers do not have personal identity cards/occupational identity cards (a mere 700 have obtained labour cards). This has hindered access to schemes and relief packages announced by the state post COVID. Indha Mahoor, Senior Programme Manager, Hasiru Dala says, “There are several challenges, like server problems, problems receiving OTP, need for occupation certificate that needs to be obtained from the BBMP and then the general issues such as phone numbers not linked to Aadhaar or ration card and bank linkages.”

~~~

The recycling chain in the city is intricately woven and connected at multiple levels. The pandemic presents an opportunity to relook at current waste management practices, budgetary allocations and priorities, and most of all the people who work in waste. It is time to look from the perspective of creating sustainable livelihoods, that treat people with respect, as important stakeholders contributing significantly to the environment, rather than mere service providers.

Well done , with cooperative efforts n participation of local authorities’n stake holders like waste pickers n recyclers who should be classified as’true environmentalists ,’waste management in the country can be sincerely ‘honestly n successfully handled…