“Three decades ago, the lanes of Chennai were adorned with a thick canopy, the shadows of which protected us from heat,” recalled V Latha, a retired BSNL employee. “Today, that green canopy is gone to make space for tall, concrete buildings, leaving us exposed to the harsh sun.”

Latha, who is associated with organisations like the Sabari Green Foundation and Senior Citizens Forum, was speaking at a webinar organised by Citizen Matters Chennai on April 30th, titled ‘Why does Chennai feel hotter than ever before?‘

Travelling down memory lane, Latha reminisced about those bearable summer years during the 1980’s when the city had abundant greenery and water bodies. “Loss of greenery, pollution in water bodies and water scarcity are interlinked with harsh summers,” added Latha. “Decades ago, citizens used to sprinkle their homes with water to beat the heat. But we can’t afford to do that now”.

While every long-time Chennai resident echoes Latha’s sentiments, there is also need to corroborate them. Is Chennai really getting hotter in absolute terms? What do the temperature trends over the past decades suggest? What does climate resilience mean for a city like Chennai? And is there a way out of these brutal summers for the common man?

To catch the entire discussion with our panelists, watch the session here: https://youtu.be/F9BG-ZvTPPo

To summarise, the speakers took a deep dive into the following issues:

Are temperatures spiking?

Geography plays a key role in setting temperature patterns. “How hot it feels is different in different locations,” pointed out K Srikanth, a weather blogger who blogs about Chennai Rains. “For example, a 35°C with 70 percent humidity in Chennai feels hotter than 42°C with 50 percent humidity in New Delhi”.

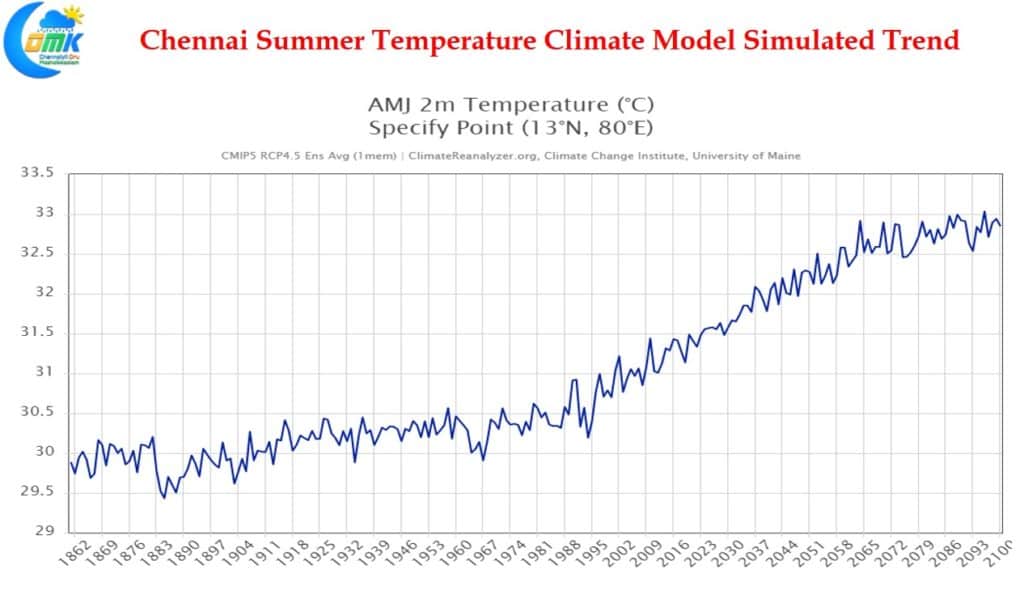

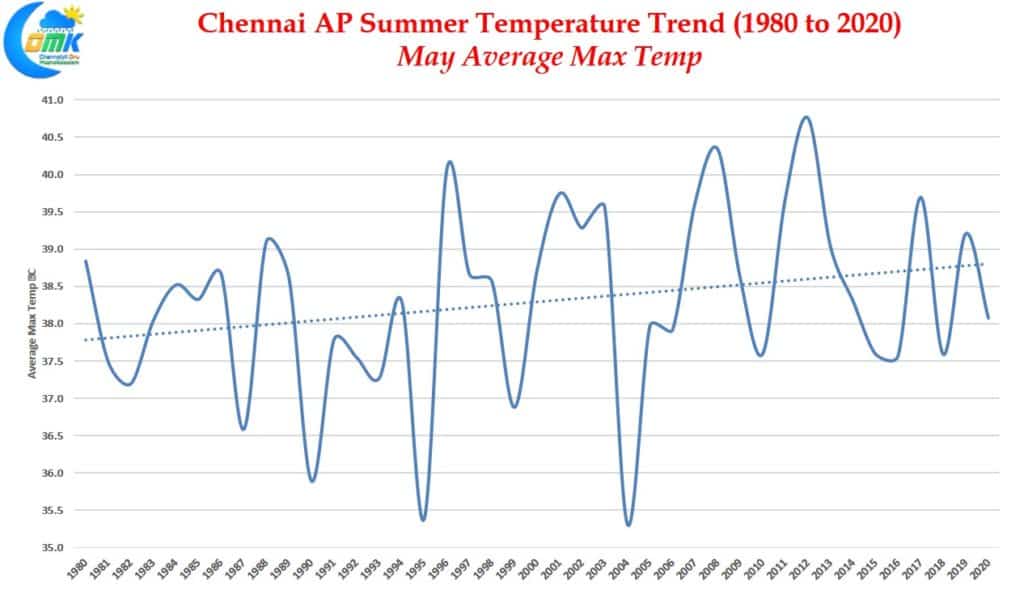

Data from 1980-2020 suggests a slight rise in the average maximum temperatures in Chennai during the summer months (April, May, June). “Post 2000, the number of hottest days in Chennai (above 40°C) in May (the hottest month of the year) has slightly increased,” said Srikanth. “There used to be 14 to 15 hottest days in the early 1980’s in Chennai. Post 2000, we have had at least two years with more than 20 hottest days in May. And climate models for the city indicate an increase in summer temperatures in the coming years”.

But the small increases in temperatures over the decades is definitely not the main issue here. It is important to acknowledge the elephant in the room: the heat island effect which makes us feel hotter than it actually is. And the main reason why Chennai today feels hotter than ever before. ‘

Read more: Understanding Chennai summers: Where did the sea breeze go?

“In Chennai, about 20,000 hectares of land was converted to built up area in the past twenty years,” said Dr A Nambi, Director, Climate resilience practise of World Resources Institute, India. “We also lost about 80 percent of wetlands and waterbodies in the past 40 years. Land use change is the biggest influencing factor for the heat island effect”.

Have we adapted to the heat?

“We are so dependent on the sea,” explained Shilesh Hariharan, Principal Architect at Madras Terrace Architects and Assistant Professor at MEASI Academy of Architecture. “The diagonal wind direction that moves towards the sea and away from the sea is what has been the life-source of the city’s built environment”.

Giving an example of the correlation between the growing city and rising temperature, K Srikanth pointed out how “after high-rise buildings came up in ECR and OMR, the southern suburbs receive sea breeze a few hours later than before”.

Increased occupancy loads and density in the built environment are other factors causing the temperature rise. “Natural ventilation is a challenge in most homes,” said Shilesh. “In our climatic conditions, the fundamental principle for any design is cross ventilation and enough shaded light (not direct light).

Over the years, citizens of the city moved away from the traditional ways of construction such as Madras Terrace Roof. “It takes longer for the heat to seep in through the Madras terrace roof that has layers of packaging to it,” explained Shilesh. But today’s buildings are dependent on external cooling entities such as air conditioners that increase the emission of greenhouse gases, which is one more cause for rising temperature.

Read more: Why some parts of Chennai felt hotter than others this summer

Victims of excessive heat

But a large chunk of the city’s population cannot afford air-conditioners. There is also a significant section of the working population such as construction workers who have no shade over their heads even when mercury levels spike.

What measures should they take to avoid heat-related issues? “Exhaustion during heat waves could lead to a heat stroke,” said Dr S Muthu Chitra, Professor and Head Of ENT Department, Kilpauk Medical College. “But there are no scientific symptoms for a heat stroke. Most times, the victim just feels tired.”

“When temperatures are 4 to 7 degrees above normal, people working outdoors should be aware of heat waves,” said Dr. Muthu. “Typical heat stroke indicators are electoral imbalance, dehydration, excess tiredness. Taking a lot of fluids to compensate for the fluid loss helps one cope with the heat. There is also a need to change the working hours during summer, like how Saudi Arabia has done”.

Proposed solutions

Policy wise, what can be done to mitigate the effect of heat islands? What role can citizens play to make the city cooler?

“Policies to increase the green cover should be encouraged,” said Dr Nambi. “For example, a city in Kentucky does a periodic canopy survey at the street level to learn the loss of tree cover due to the advent of new buildings and charts plans to compensate for the loss.”

Read more: Summers are getting worse in Chennai. How can we build cooler homes?

Chennai can also build better by following simple steps such as retaining the greenery, ensuring cross ventilation and using heat resilient materials in construction. “As Chennai is set to enter into the third master plan from 2026, there is a scope to devise solutions for these problems,” said Shilesh.

But until at least some of these solutions are implemented, all that the common citizen of the city has to protect him/her from the heat is to cover their heads with a dupatta or handkerchief.