On March 30th, the Meenambakkam weather station in Chennai recorded a high of 41.3 degree C, beating the all-time record for the hottest day in March in the city. The last time Chennai witnessed such a peak in temperature was when the Nungambakkam station recorded 40.6 degree C on March 29 1953. The second-highest temperature recorded by the Meenambakkam station was on March 31 2014, when the observatory registered 39.2 degree C.

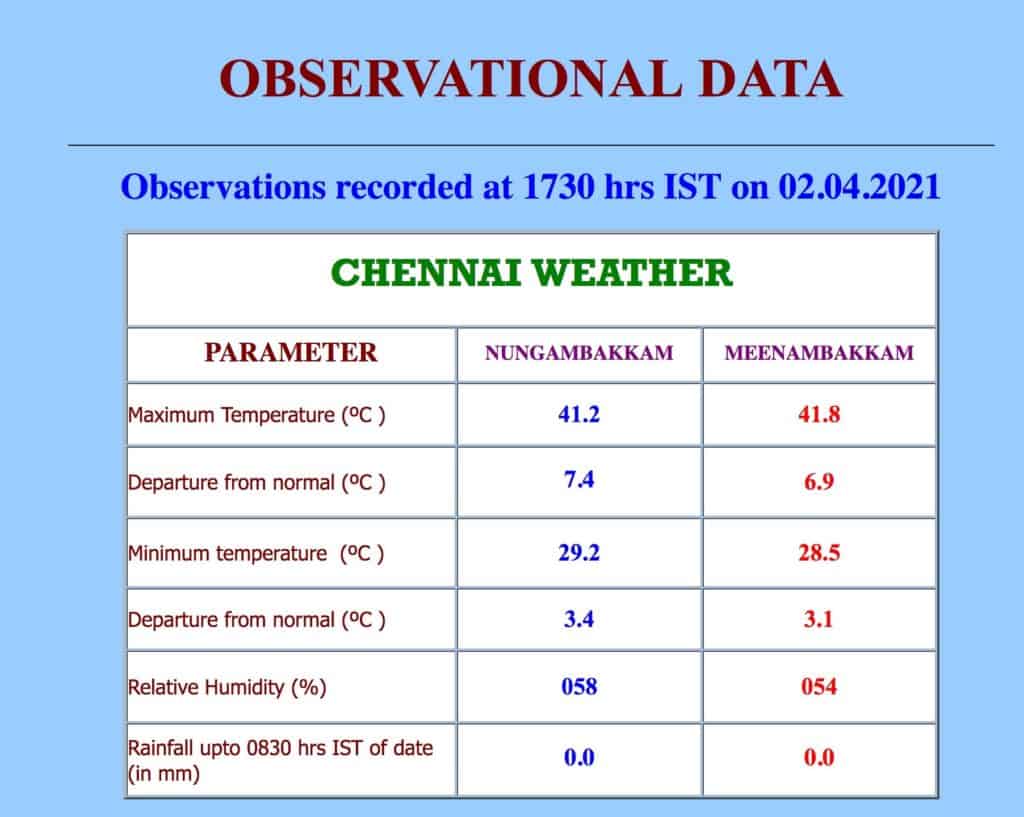

Just two days after the mercury touched its highest ever in March this year, the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) announced (on April 1st) the likelihood of Chennai’s temperature shooting up by three or four degrees above normal until April 4th and the occurrence of heatwave-like conditions.

Hot summers in Chennai are a way of life. Anyone who has spent a summer in Chennai knows we also tend to sweat a lot in Chennai which is due to the presence of humidity (presence of water vapour in air). “As a coastal city, the humidity is high in Chennai unlike New Delhi, where people may not sweat even if the temperature reaches 40 degree C,” says K Srikanth, a popular weather blogger.

But the usual summer trends apart, cases of rising temperatures and overall heat stress have been shooting up at an alarming rate over the recent years, raising concerns over global warming and climate change.

Read more: Ways and methods to stay cool in the Chennai Heat

Dog days

While Chennai recorded an all-time record for the hottest day in March even before the onset of kathri summer (also known as dog days), March is hardly what you’d consider the peak of the summer season. “The wind direction changes from westerlies to easterlies by the end of April, which is when the city experiences further rise in temperature; that is when the actual summer begins for us,” adds Srikanth.

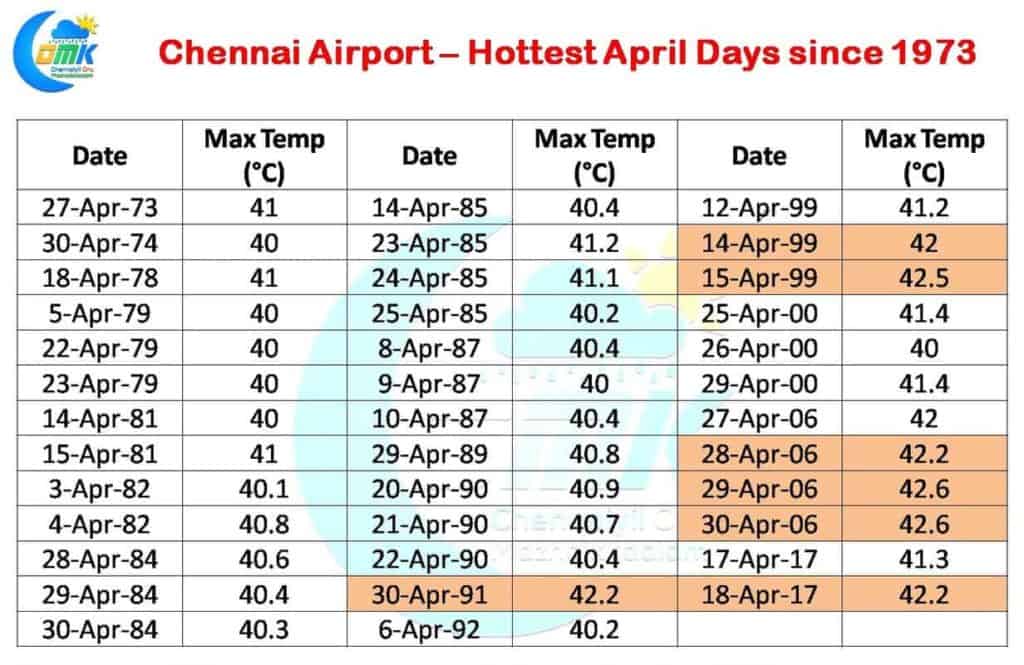

In colloquial parlance, the beginning of Agni Nakshatram according to the Tamil almanac marks the beginning of khatri summer (hottest season). “Khatri summer is not a scientific meteorological term. The temperature hits a peak during May which is locally referred to by the term. The maximum temperature in May often goes up to 41-42 degree C in Chennai,” states S Balachandran, Deputy Director-General of Meteorology, Chennai.

On May 19 2020, Nungambakkam weather station recorded 41.3 degree C and Meenambakkam recorded 41.4 degree C. On May 3 2019, the temperature rose close to 40 degrees Celsius in Nungambakkam and 42 degree Celsius in Meenambakkam. Surprisingly, 2018 May recorded pleasant weather in Chennai when the mercury did not touch 40 degree C at all.

Heatwave incidence

Heatwave is a phenomenon characterised by very high temperatures in a place over a period of time. It is a condition, when the air temperature becomes severely damaging, or even fatal, for the human body when exposed. Quantitatively, it is defined based on the temperature thresholds over a region, in terms of the actual temperature or its departure from normal. As Balachandran clarifies, in Chennai, heatwave-like conditions are said to occur when the temperature crosses 37 degree C for two consecutive days. Rise in temperature, strong westerly winds, the position of clouds, distance from the equator, moisture and sea breeze are some of the factors that affect the incidence and intensity of heat waves.

“In the city, heat waves may not be as intense as in the interior parts of Tamil Nadu. Chennai being a coastal city with tropical climate, it depends upon the sea breeze for respite from brutal summers in the afternoons and evenings,” Balachandran adds.

But the city has experienced quite a few heat waves in the last few years. In May 2019, Cyclone Fani left a sizzling impact on the city with the mercury levels hovering around 40 degrees C, which is a departure of four degrees from the normal, causing a heatwave.

A month later in the same year (June), Chennai recorded 41.1 degree C and the day temperature remained at 40 degree C well after 2 pm as the sea breeze set in late due to strong westerly winds. The city continued to witness heatwaves for 15 days in June 2019, making it the hottest month that year.

In April 2017, Cyclone Maarutha made a landfall on the west coast of Myanmar, absorbing a great amount of moisture from the coast of Tamil Nadu that resulted in a weak sea breeze. As the temperatures crossed the 40 degree C mark, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) had issued a heatwave warning for several districts in TN, that included Chennai too, on April 15 2017.

Read more: Cyclone Fani effect: How is Chennai coping with the heatwave?

The blessing of the sea breeze

Sea breeze occurs in coastal areas as there is a temperature gradient over land and water. The surface temperature of the land goes up during the day time, due to which air particles rise and humid air from above the sea moves into the land, thereby bringing some respite from high temperatures. This can be felt in areas like Mylapore, Besant Nagar, Thiruvanmiyur and Tiruvottiyur and other places that are located near the coastline.

For Chennai, the normal time for the sea breeze onset is around 11.30 am in March and April. There are occurrences, however, of delayed sea breeze due to westerly winds. For instance, in May it could start blowing in around 12.30 pm. Sometimes, when the westerly winds are really strong, the sea breeze may get delayed even further, or not blow at all, leading to warmer afternoons and evenings.

Over the past four years, weather observers note that there has been a regular delay in the arrival of the sea breeze in south Chennai and suburbs. “When compared to north Chennai, the sea breeze is slightly delayed in the south and suburbs. This can be attributed to the nature of the localities along the coast. The North Chennai coast does not have high-rise structures, that are abundant on the southern side; the presence of high-rise buildings can potentially block wind movement. Hence, I feel it could possibly be linked with the concretisation and construction along the OMR belt,” says Srikanth.

Read more: Summers are getting worse in Chennai. How can we build cooler homes?

Urbanisation as the culprit

Another factor leading to hotter summers is the urban heat island effect. It is a phenomenon where some pockets of the city experience significantly higher temperatures than the surrounding locality, caused primarily by urbanisation and human activities leading to loss of green cover and emission of greenhouse gases.

For example, a study conducted by four researchers at the Anna University Center for Climate Change and Adaptation Research in 2014 showed that the maximum intensities of temperature were noticed in the central core city and north Chennai, which are distinguished for their commercial centers and densely populated residential areas. In morning time, temperature differences between the fringes and central parts of heat packets were in the range of 3–4.5 °C.

The findings showed new heat pockets around Aminjakarai-Poonthamalee Highway, Medavakkam, T.Nagar, and Ennore. These heat pockets recorded increased temperatures by up to 1.5–3.0 °C in the morning hours and 1.5–5.5 °C in the evening hours (compared to the temperature recorded at thermographs of Nungambakkam station). The authors note that the following local characteristics could have contributed to increasing temperatures here:

- Aminjakarai — a highly urbanized zone

- Medavakkam — an emerging urban centre that has seen the development of information technology and industrial sectors in surrounding areas during the past decade. The two landfills situated in the vicinity also influence the temperature

- T Nagar area is again a residential and well-known commercial area

- Ennore is an industrial area, housing a number of big manufacturing units

The study points out that land use and green cover play a critical role in the microclimate of these and other regions. It therefore urges the city administration, policy makers and architects to take up effective mitigation and adaptation strategies to make summers more comfortable for the people.

Also read:

Simple answer. Wrong planning which has resulted in high rise buildings blocking the strategic windways from the ocean into the city and the passage of wind. Tessaloniki , another seaside city also has made the same mistake.