Thirteen-year-old Rohan (name changed), a little shy and very happy, envelops his mother in a spontaneous bear hug as three of his teachers and therapists compliment and tease him playfully. We are at Rohan’s house in one of the bylanes of a bustling informal settlement in Dharavi. His mother, Mayadevi Jagannathan, cradling a two-year-old daughter, beams proudly as she says that now Rohan even helps her by keeping an eye on his younger siblings. This is significant for Mayadevi and Rohan’s therapists. Born with intellectual disabilities, he has come a long way, from not attending school as a child to now going to a mainstream school nearby.

Rohan is one of the students receiving therapy and educational support at home through the community programme run by ADAPT, formerly known as Spastics Society of India, an NGO in Mumbai. Gulab Syyed, who runs the programme in Dharavi, says that taking intervention measures home to students who cannot reach school plays an important role in their development, as evidenced in Rohan’s case.

A case for home-based education

Under the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, there is a provision to give home-based education for children with severe or multiple disabilities up to grade 12. Through this scheme, 72,186 students were covered with an outlay of ₹20.68 crores across India in 2023-24.

In theory, government-appointed resource persons visit allocated areas to verify out-of-school children with disabilities. After taking basic information about the child and family, including the medical history, the resource persons undertake a case study. They then conduct an assessment of the children’s educational and daily living needs and create an intervention plan. The individualised intervention is carried out in fifteen-day cycles, and parents are trained during each cycle to continue the teaching at home until the next session. If necessary, teaching plans are modified based on the feedback from the parents.

Read more: The inclusion gap: Challenges facing Mumbai’s special educators

Practically, things may not pan out this way. T Shaheen, who lives in Bengaluru, has a fifteen-year-old daughter. When she could not walk as a toddler, Shaheen and her husband took her to the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), where she was diagnosed with Systemic Mastocytosis (SM), a rare and chronic disorder. In patients with SM, excessive mast cells, a type of white blood cell, are produced and accumulate in organs. This results in a continued allergic reaction, affecting the organs.

Till she was fourteen, Shaheen carried her daughter to school. She says, “Now she has grown. I find it difficult to carry her. So, she studies online.” Moreover, the school did not have a lift. The school has agreed to let her write exams, but does not provide much by way of support. They sent her some notes and have asked her to download an app for studying.

Challenges of access

But many parents like Shaheen may not be able to access these tools. Moreover, while the availability of textbooks is important, they cannot take the place of the guidance provided by a special educator. Shaheen’s voice is a mixture of distress and despair as she recounts the difficulties in educating her daughter. A school opposite their house is refusing to admit her, though Shaheen has offered to make arrangements for a wheelchair that others can use too. This, even though under Samagra Shiksha, no school is allowed to turn away a student. The provision for home-based education, if applied properly, would have helped her daughter to access education.

Tools for home-based learning

The Department of School Education and Literacy under the Central government has several resources, including an app called ePathshala. The app has NCERT books and learning content for students, teachers and parents. In addition to this, the Ministry of Education has also created an online ISL dictionary and audio books. Lessons in ISL are also uploaded on the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS) YouTube channel.

Under Samagra Shiksha, schools are expected to identify students with disabilities and take up assessments of their educational needs. Moreover, they are supposed to provide teaching-learning material, assistive devices and aids. CIET and NCERT have also developed a screening checklist and app PRASHAST for teachers and special educators. It enables them to identify students with disabilities.

While many children manage to study online, 27-year-old Apoorva Suresh sees the lack of access to schools as a missed opportunity. She was forced to end her education at fourteen due to myopathy, which progressively weakened her muscles and limited her mobility. Frequent health issues such as dizziness, cramps, and fever further halted her studies. With little external support, Apoorva could not complete her formal education and wishes she had access to home-based learning.

In stark contrast to this, the home-based intervention Rohan received in his early years served him well. When he was just three, his mother, Mayadevi, fell severely ill. To recuperate, she moved to her home city of Tirunelveli. With no school ready to admit Rohan, ADAPT stepped in. Already familiar with his case, the social workers provided her support over the phone. They trained her to feed him, taught her activities such as sorting to develop his motor skills, and to reduce his hyperactivity.

Role of parents

Thanks to those initial efforts by Mayadevi, Rohan is able to attend school today. This underscores the crucial role of parents in home-based education.

Vaishali Pai, an occupational therapist and the founder of Tamahar Trust in Bengaluru, also lays great emphasis on the role of parents in the educational progress of children with moderate to severe disabilities. A study that she and her team conducted shows that in moderately disabled children, parental involvement enables the child to make an eight-and-a-half-month developmental leap over 12 months.

“Parents are the force behind the child’s progress,” adds Iteshree Date, the Director of Education Services at ADAPT.

Read more: Most urban schools violate law, exclude children with disabilities

Prasanna Shirol, Co-founder and Director of the Organisation of Rare Diseases India (ORDI), and his wife, Sharada, are a testament to this. Their daughter was the first diagnosed Pompe disease patient in India. Pompe disease is a rare genetic disorder which causes progressive weakness of the respiratory system and the muscles. They moved homes so that they could be close to their daughter’s school. Moreover, Sharada would carry their daughter up two flights of stairs and wait outside the classroom to bring her back. Despite their herculean efforts, they lost their daughter as the ventilator malfunctioned when she was attending college in Bengaluru.

Prasanna explains that home-based education becomes necessary in two situations: when the student has a locomotor disability or has health-related challenges. Commuting can be a problem in both cases. Chronic diseases also weaken children’s immune systems, leaving them vulnerable to infections. Further, some children may require frequent hospital visits.

Another difficulty is that such students often need someone to accompany them to their place of education, a resource not every family can afford. Prasanna further points out, “Even if you have a helper, and even if the child can attend school, do our schools and colleges truly have the infrastructure they need, such as accessible toilets and other facilities?”

Read more: One step towards inclusivity: Free higher education for transgender students in Maharashtra

Monumental challenges for parents

“The idea of home-based education is that families learn and carry it out when centre-based learning isn’t accessible. But in reality, this rarely happens,” explains Vaishali, highlighting parents’ struggles.

For many families, especially in lower-income groups, both parents must work to survive. Gulab points out that her students’ parents often work as cleaners, domestic workers, taxi drivers, or vegetable vendors, jobs that are already physically demanding. On top of this, they are expected to act as caregivers, educators, and even therapists for their disabled children, which adds immense pressure.

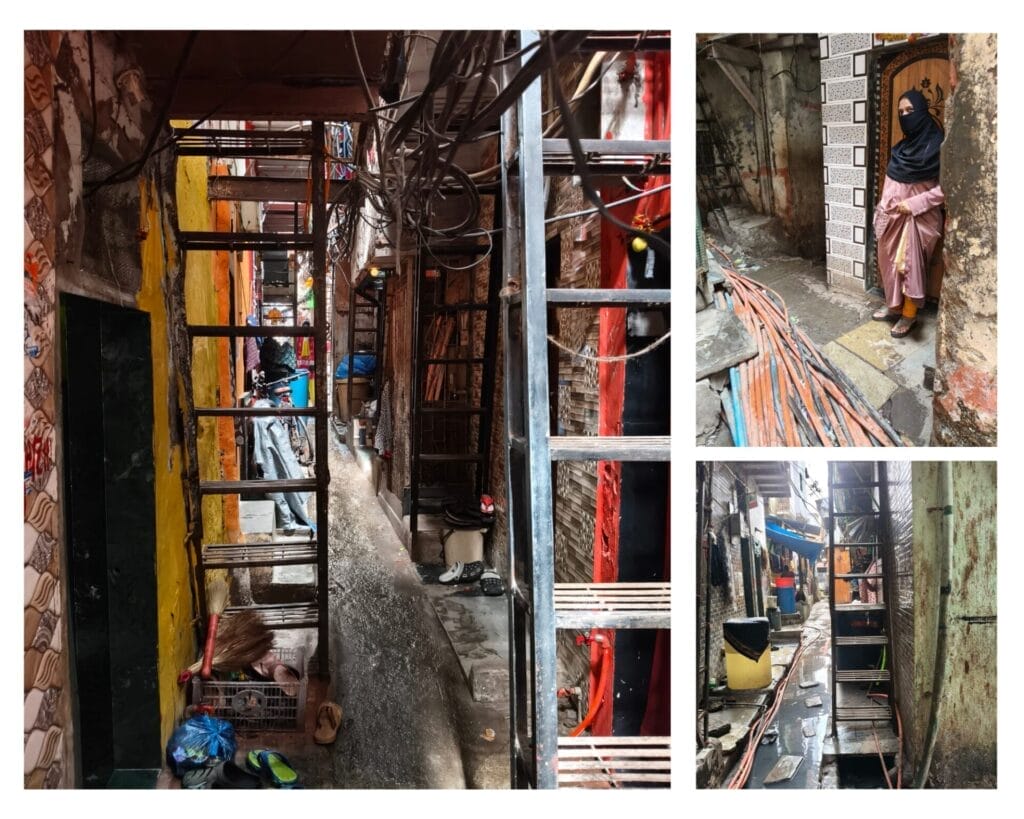

Moreover, living in an informal settlement comes with its own challenges. The lanes are so narrow that it is impossible to use a wheelchair. Walking while carrying a child in one’s arms also poses the danger of falling. Gulab and Ruksana Sayyed, who also work at ADAPT, are residents of Dharavi themselves. They have witnessed these challenges first-hand. They cite cases of mothers who have developed severe health issues after repeatedly carrying their children to the school or therapy centre.

Besides this, life is tied to rhythms like filling of water, which is available for a short period, leaving them little time to teach their home-bound children. Battling on so many fronts also leads to mental health issues, especially for mothers who, in most cases, are primary caregivers.

Vaishali says that in urban middle-class and upper-middle-class families, there is a denial of the child’s condition. The focus is on fixing the problem, rather than providing support to the child.

Support and awareness initiatives for parents

Iteshree believes that parents need to be educated about the importance of maintaining a feedback loop with the resource person. She adds that sometimes parents do not inform them that the child is unwell or has undergone surgery between visits.

Experts agree that there is a dire need for awareness among parents. The struggle begins with getting the correct diagnosis in children with chronic diseases. After that, parents have to grapple with finding the right resources to continue their education. Shaheen, whose daughter is keen to continue her education, says, “Non-disabled students can go anywhere to get an education, but who will teach children who are home-bound?”

One of the key issues, according to Vaishali, is that parents do not understand what the child is going through. She suggests training parents in trans-disciplinary interventions. Such a programme would cut across rehabilitation disciplines targeting communication, fine and gross motor skills, etc., through a single activity.

It is also crucial that parents have access to help for mental health issues and support from the extended family to teach the disabled child.

What will make home-based education truly accessible?

- Accessible and clear guidelines on how parents can make home-based education available for severely disabled children under Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan.

- Training for parents on their role in home-based interventions.

- Facilities to nurture the mental health of parents who act as caregivers, and educators in home-based interventions

- Development of trans-disciplinary curricula with activities that target multiple skills with one activity.

While home-based education is a commendable initiative, its success depends on access to both physical and financial resources.

This article is a part of our work supported by the Sudha Mahesh grant, exploring how inclusive education can bridge gaps in access and equity for children with disabilities or special needs.

Also read:

- Beautiful minds: Empowering artists with autism

- Accessibility: Mumbai’s lifeline can make lives of people with disabilities easier, but how?

- Inaccessible public transport: Small changes can go a long way for differently-abled