When Cyclone Michaung-induced floods hit the resettlement colonies of Perumbakkam, the houses on the ground floor were quickly inundated. On a priority basis, persons with disabilities were allocated houses on the ground floor. However, with the floods, their vulnerability pushed them further to the fringes. They were forced to climb stairs seeking refuge in other people’s homes that already had leaky roofs and damp walls.

This was not the first time people in resettlement colonies in Perumbakkam or Semmencherry were facing floods. Almost every year, November and December are months of struggle for the families, who are evicted and resettled in various sites located in the peripheral areas of the city. Forced to move away from their homes because of natural disasters, these families face inundation almost every year even after relocation, reveals a study by the Information and Resource Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC).

While the data shows that 95% of the evictions were carried out for the ‘restoration of water bodies’ in Chennai since 2015, Perumbakkam, one of the resettlement areas where the displaced families were relocated, has faced flooding in the years 2015, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2023. Such instances of flooding exacerbate the existing vulnerabilities of families already facing challenges related to loss of livelihood and income in the post-resettlement phase.

The IRCDUC report titled ‘Resettled in the paths of floods — Perennial floods expose the fundamental flaw of the existing resettlement programmes in Chennai’ published in December 2023, exposes the shortcomings of the government’s resettlement plan. Here are some key points from the report:

Read more: In Chennai’s resettlement colonies, life comes full circle with the floods

Impact of 2023 Chennai floods in resettlement areas

The report detailed the ordeal that people in Semmencherry and Perumbakkam went through during the December 2023 floods.

According to the report, when sewage-contaminated water entered the houses on the ground floor, the families there requested the first-floor occupants to accommodate them. However, for those on the first floor, accommodating their own families is a challenge as the houses are just 160 sq. ft. wide. Stranded on the ground floor, families were left without access to safe accommodation. They were also unable to safeguard their belongings, most of which were lifetime savings.

Similarly, in Perumbakkam, almost the entire settlement was engulfed with flood water and people were stuck inside high-rise buildings without water supply and electricity. Without power supply, the elevators did not work and there was no way of providing drinking water through overhead tanks, as the motors were not functional. The water sumps were also contaminated with sewage. The people in the settlements were forced to use contaminated water for drinking and other purposes. It was only after protests, that tanker lorries supplied water to the community.

Post-disaster eviction in Chennai and resettlement to vulnerable locations

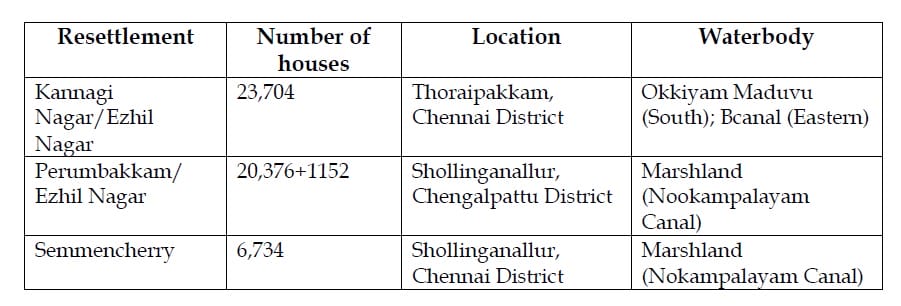

The report notes that since the 2004 tsunami and the 2015 Chennai floods, over 23,000 families were resettled in sites like Perumbakkam, Ezhil Nagar, Semmencherry and Kannagi Nagar. Since 2015, 83 settlements comprising nearly 19,817 families were evicted. These families evicted as part of ‘flood mitigation measures’ and ‘restoration of water bodies’ were resettled in sites that are located in the path of floods and ecologically sensitive areas.

“From 2015 to 2023, 12,045 families were resettled in the site of Perumbakkam for the restoration of water bodies. Since 2015, Perumbakkam has faced flooding in the years 2015, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2023. However, there were no efforts to stall the expansion of the settlement even though it faced flooding almost every year,” highlights the IRCDUC report.

Citing experts, the report says, “Since the early 2000s, over 43,000 resettlement tenements have been built in Kannagi Nagar and Ezhilnagar (on the Pallikaranai marsh), and Perumbakkam. Kannagi Nagar and Ezhilnagar were developed on a large tract of marshland that served as a buffer for floodwater moving eastward from northwest and southwest. These areas also have water bodies such as the Thalambur and Perumbakkam lakes, which are part of historically established flood pathways. During heavy rains, these lakes will fill up and breach their banks, whether naturally or deliberately resulting in intense flooding in these sites. The creation of mass ghettos of urban poverty in the middle of ecologically fragile lands exposes the fraudulence of both the environmental and the socio-legal rationale of resettlement.”

Read more: Residents in resettlement colonies struggle with many aspects of daily life: IRCDUC study

Continuing expansion even after facing many floods

Since 2015, Perumbakkam has constantly been inundated. Despite this, the Tamil Nadu government expanded the resettlement site there constructing an additional 1,152 houses under the Light House Project (LHP) under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY).

Ironically, these houses were considered to be ‘eco-friendly construction fit for diverse climatic quality standards and disaster-proof houses.’ However, the recent flooding has proven otherwise.

“A closer look at the location of various resettlement sites constructed by the Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board (TNUHDB) confirms that many of these sites are located in or closer to ecologically sensitive areas,” notes the report.

Likewise in Kannagi Nagar, which is situated on the banks of Buckingham Canal, flooding was not the only issue. Poor quality of houses and leaking roofs added to the problem.

Recommendations from IRCDUC

IRCDUC has given the following recommendations for the issues

- Even though a draft policy on Rehabilitation and Resettlement (R&R) was released in October 2021 by the Government of Tamil Nadu, the policy has not been finalised yet. One of the points made in the policy is that resettlement sites should not be in “lands which are located in the buffer areas of ecologically sensitive zones, protected areas, the forests, lands which are affected by industrial pollution, and environmental degradation.” Therefore there is a need to finalise the policy to prevent such housing programmes in eco-sensitive areas.

- The ‘Resilient Urban Design Framework’ of the TNUHDB must be translated, relooked and strengthened by engaging in public consultation with technical and social experts and implemented in all the housing projects. Unless the same is incorporated in the existing housing policy and the draft R&R policy, such resettlement sites and housing projects unmindful of the disaster risks and vulnerabilities will continue to be constructed.

Placing people in flood-prone and ecologically sensitive areas in the guise of restoring waterways has only multiplied the woes of communities that were already struggling after displacement. It is high time the authorities undo their mistakes and ensure safe housing.