December 2015 — a date that Chennai is unlikely to forget in a long time to come. The ruthlessness of nature coupled with an unprepared civic administration created one of the worst floods that any city in India has ever seen. But if there was anything good about the floods and their aftermath, it was the awareness created among large sections of citizens about the need to restore and preserve the water bodies in the city.

Among the many water bodies that were identified to be in need of a major makeover was the Buckingham Canal. Several discussions, research and leisurely activities have been organised around the canal in attempts to create awareness of its history and significance to the city.

One such was Eyes on the Canal, an initiative under the Cities Fit for Climate Change Project, conceived of as an exercise in participatory planning to re-imagine the once-integral Buckingham canal as part of the community. It was envisioned to increase involvement of stakeholders so as to revive the canal and associated ecosystems, and by extension make Chennai climate-proof.

The initiative floated an open ideas competition that called for participating teams to submit proposals for a 3.5 km stretch of the canal, between the Kotturpuram MRTS station and the Thiruvanmiyur MRTS station.

The Buckingham canal is a man-made navigation canal, originally built in the 1800s as a means of transportation of goods to, from and within the city. The canal linked the three rivers – Adyar, Kosasthalaiar and Cooum – and played a crucial role in flood mitigation in Chennai.

Over the years, however, it has suffered heavily due to dumping of garbage and sewerage, encroachments and neglect. Once navigable and snaking along the city for a length of 31 kms, the canal is now completely blocked in parts and a narrow ghost of its past in many others stretches.

The Eyes on the Canal competition called for ‘visionary, but feasible’ ideas to improve the Buckingham canal, making it livable and climate-proof.

The winning ideas

After deliberation by an eminent jury, three winners were declared on October 21st. Two teams were placed joint-first while one team took the third place. The winning teams will, over the next three months, evolve the ideas pitched in their proposal and work closely with local authorities to find feasible avenues for their implementation.

So, what are some of the climate-proofing solutions that have emerged from this innovative exercise and what could be the transformation that is feasible for the canal from its current state?

“We have created a toolkit of water sensitive infrastructure that can be applied at the building, street and city level. Through a network of green infrastructure projects such as rain gardens, green roofs, bioswales, constructed wetlands and filteration islands Chennai can become resilent to some of the risks it faces from future sea level rise and storm surges due to climate change,” says Bina Bhatia, principal architect and urban designer at The Blank Slate, Mumbai, which was placed third in the competition.

The proposal looks at the Buckingham canal as an asset that was designed to provide climate resilience. Bina notes that some of the areas immediately surrounding the canal escaped the worst of the Chennai floods in 2015 as a result of the canal’s ability to mitigate the effects. But the biggest issue that it now faces is the dumping of garbage and release of untreated water from the surrounding areas.

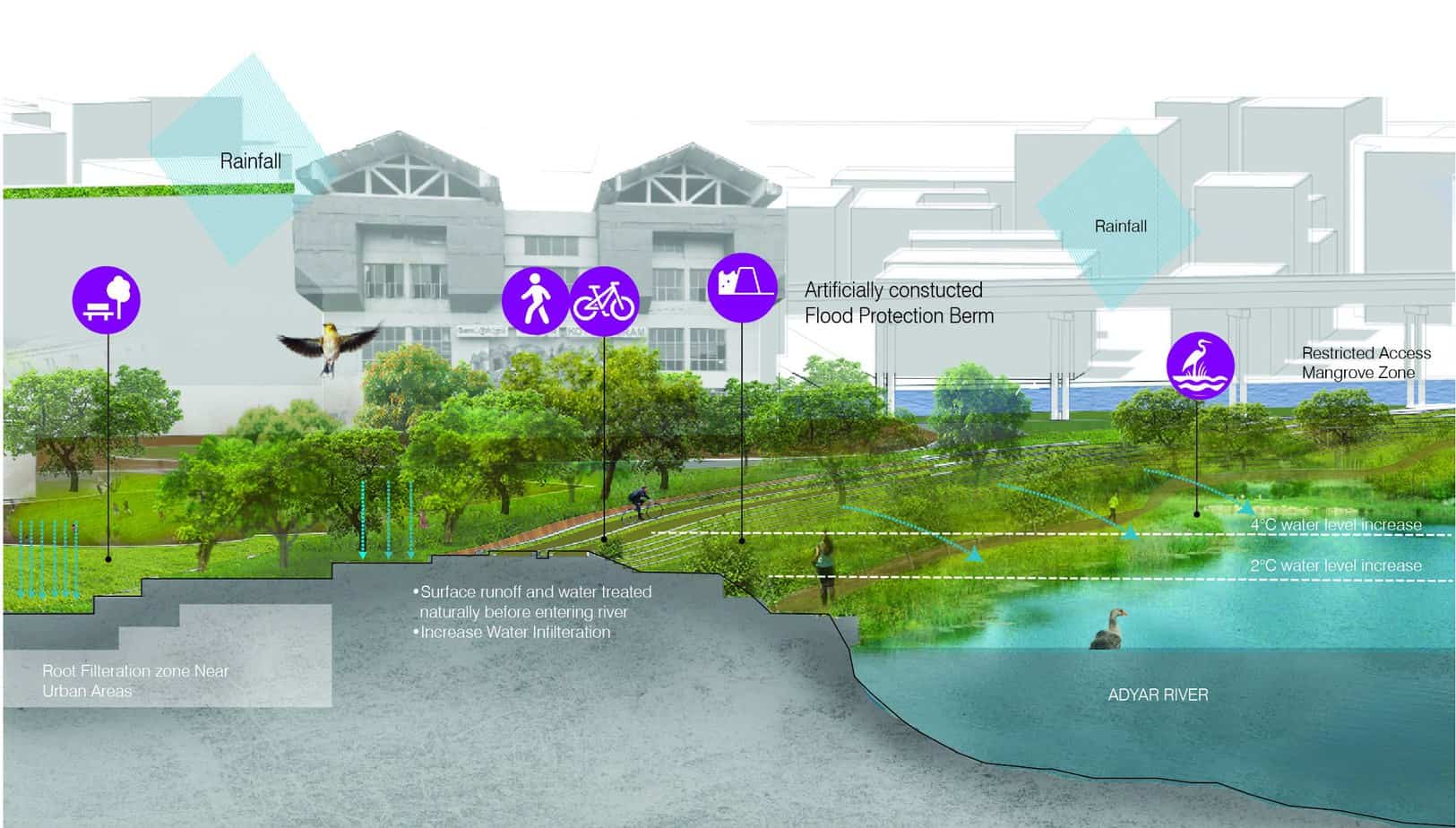

The proposal by the team from Blank Slate takes a holistic view of the canal to suggest alternative methods of waste and storm water management. The toolkit at the city level addresses ways to deal with waste and stormwater as well as the flooding in the Adyar river. A Berm, an artificial embankment, is proposed at the mouth of the Adyar river to deal with flooding. A sustainable eco-park is also a part of the proposal.

“When you create flood infrastructure you do not want to create huge walls or barriers but instead, create accessible community spaces that act as public spaces during other times. The naturally landscaped berm and the ecological park could set examples, as they mitigate floods and protect the low lying regions of Adyar when necessary but function as a vibrant green zone for the city otherwise,” says Bina.

Other elements pitched by the team include a biosphere on each street and a water square, which is a plaza designed in a manner that it can hold excess water during rain and helophytes, plants that act as floating islands and purify the watering the canal. The aim is to make the canal a public space by finding suitable access to existing neighbourhoods around the canal.

The various elements of the proposal can be replicated across the stretch of the canal while some are specific to the 3.5 km stretch. In the coming months, the focus will be on identifying sites on the ground for follow-up and assessing the practicality and feasibility of the ideas pitched.

People at the center

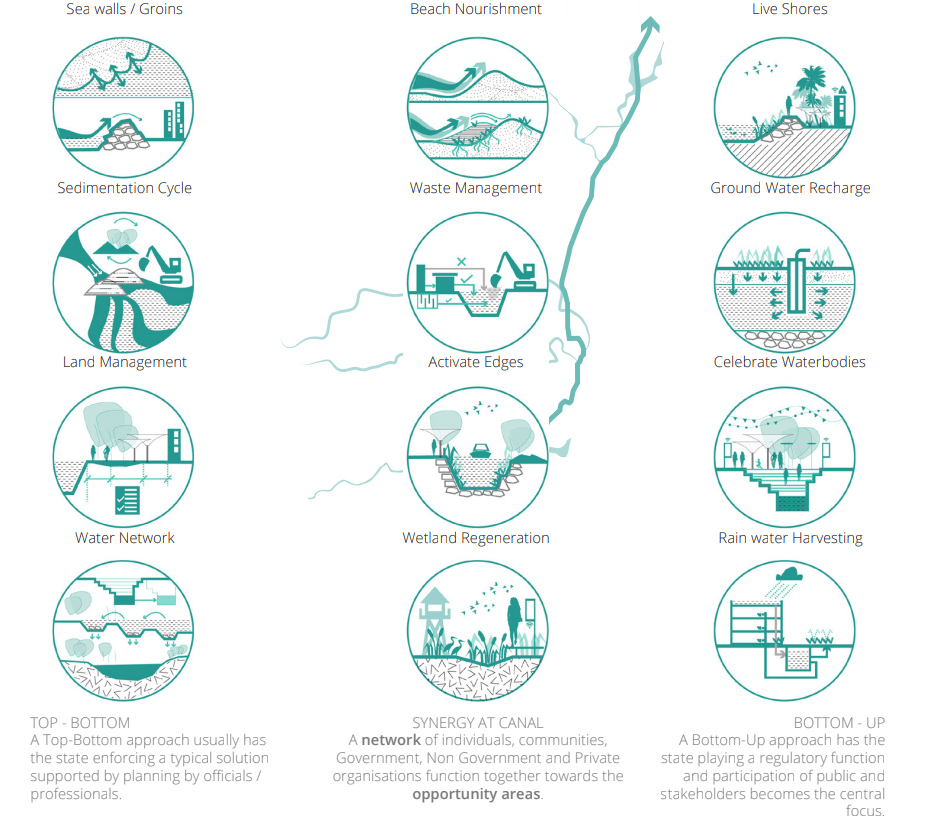

The five-member team from StudioPOD, Mumbai adopted a people-centric approach in a proposal that placed it jointly at top position. Following the approach of successful interventions of a similar kind by Asia Initiative, the proposal looks to empower the community to take ownership of sections of the canal. Acknowledging the risk of taking exclusively top-down or bottom-up approaches, the team chose a collaborative approach wherein the “local systems work in collaboration with centralised systems” to arrive at robust solutions.

“The main idea is to keep the community as the custodian. There has to be community participation in maintenance. The strategy will involve residents, local government, corporates and institutions as stakeholders,” says Satish Chandran, Urban Designer at StudioPOD.

Community-centric approach has met with success in various initiatives such as the Matunga Flyover garden in Mumbai. Citizens came together to transform the area under the flyover which now houses a park, a skating rink and an amphitheatre.

For the Buckingham canal, the proposal covers the 3.5 km stretch but the suggested interventions can be scaled-up with stakeholders along the length of the canal. Site specific suggestions will be pitched by the team by identifying social, economic and community opportunities based on ground realities.

Following their selection, the team, along with other winners had a chance to interact with the local authorities. “The Chief Secretary of the PWD and the members of Chennai River Restoration Trust were enthused by the community-centric approach,” says Sathish.

The coming months will see an assessment of the feasibility of the ideas on the ground and identification of different community models. The team will look into integrating CSR to get companies involved, and also at branding as a strategy to bring more people to the canal.

Landscape-based approach

The five-member Team Sponge, which also bagged first place, adopted a landscape-based approach not often seen in the country but widely practised in China and the West. This approach views urban development in conjunction with the natural systems already in existence and looks to improve urbanity with respect to the natural systems.

“We looked at a 4-step water management approach that integrates neighbourhood planning, regional planning and the hydrological needs of the city. The four steps are – protect, delay, store and release. The sponge framework slows down the runoff, stores rainwater and recharges aquifers,” says Praveen Raj, Urban Designer and member of Team Sponge.

The sponge framework also focuses on the rejuvenation of the canal along with the storm water system in a way that will lead to the re-imagination of urban neighbourhoods. The approach is not limited to the canal but extends to the surrounding urban fabric by involving stakeholders such as the residents, local government and institutions. It is tied to the overall hydrological basin of Chennai.

“The approach will also improve livability and open up economic opportunities, including housing. In the next few months, we will be implementing a pilot project to demonstrate the benefits to all the stakeholders,” says Praveen.

The challenge in this approach, as shared by the local authorities, will be the navigation of necessary jurisdiction and bringing the stakeholders on board. “Ideas such as this shape up incrementally but it is important to set the vision, legally giving way for such development,” they say.

With the teams adopting different approaches with innovative elements to make Chennai climate resilient, a lot will depend on the progress made in terms of working with local authorities over the next three months. That will set the tone for the steps to be taken to revive and restore the Buckingham canal and surrounding areas, and aid the larger cause of protecting the city from the adverse effects of climate change.