Good mobility relies on a number of measures – urban planning, transportation planning and traffic flow control. In earlier parts of the series, we have looked at how urban planning and transportation infrastructure planning can actually help solve common mobility woes in our cities.

This multi-part series examines the measures needed to sustain and improve urban mobility. For a detailed discussion on each measure, check the following guides:

Part 1: Urban planning measures

Part 2: Transportation planning measures

Part 3: Traffic control measures (this article)

Also see: Action agenda for better mobility

The article How to make Bengaluru traffic jams go away analyses these measures in the context of Bengaluru.

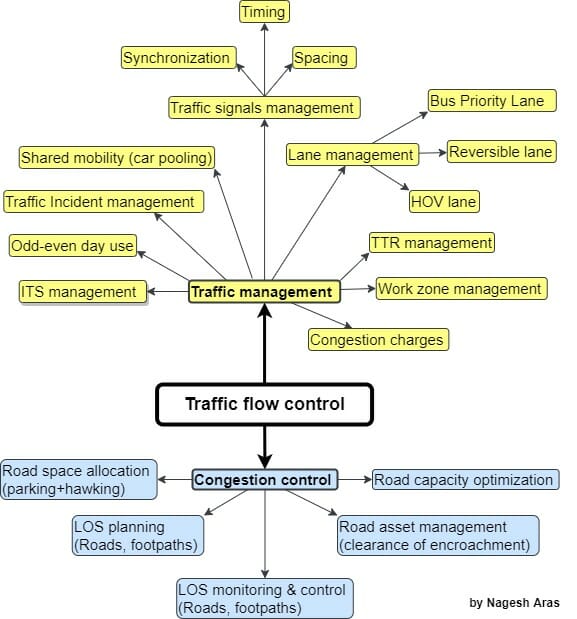

Even if urban planning and transportation planning measures are implemented, traffic will eventually build up on the city roads. Therefore, adequate traffic control measures are needed. This includes planning and managing traffic signals, lane management (e.g. reserving lanes for buses and high-occupancy vehicles, reversing a lane during peak traffic to increase the road capacity in one direction, etc.)

Also, we must implement measures to control congestion by judiciously allocating the road space for parking and street vendors in such a way that the carrying capacity of the roads is not reduced below the desired target value.

Traffic flow management

These are measures that curb, divert or distribute the vehicular traffic. They may be in the form of physical controls (e.g., signals), economic nudges (e.g., congestion charges and other demand management tools), or systems to herd/redirect vehicles (e.g., ITS, traffic incident management).

These measures are described below:

Lane management

On any urban road, the traffic flow keeps changing through the day. The traffic is usually heavier in one direction, and this direction often reverses in the evening. To maximise a given road’s capacity, lane management techniques are adopted globally. It is time for India to consider these measures.

- The reversible lane scheme is used in case of multi-lane roads where the traffic is very high in one direction, but very low in the other direction. In such cases, a lane is borrowed from the less busy side, and vehicles are allowed to go in the opposite direction in this lane.

- In the High-Occupancy Vehicle (HOV lane) scheme, any vehicle is allowed to use a reserved lane only if it is carrying a certain minimum number of passengers. Since most vehicles have one or two passengers, they cannot ply on this lane. Thus HOVs enjoy a fast lane.

- In the Bus Priority Lanes (BPL) scheme, only buses are allowed in reserved lanes.

Traffic signals

Signals can improve traffic speed significantly, if their timing is adjusted to match the geometry, so that there is no pile up at any junction.

Spacing of signals is critical: If two signals are spaced too close, that short section will fill up quickly, and cause a traffic pile up.

Automatic systems may be used to adapt the signal timing to handle the variation in the traffic flow through the day.

Signals at successive junctions of a road are synchronised to obtain green lights when a vehicle starts from one junction and arrives at the next junction.

Intelligent Transportation System (ITS)

These are advanced technology systems that make transport more efficient and safe. It is used for several purposes, including safety surveillance, calling an ambulance in case of an accident, controlling the traffic flows in the city, etc.

Travel Time Reliability (TTR)

People can rely on buses and trains only if they always run on time. In case of any rare delays, the users must be made aware of the new estimated time of arrival. Therefore it is critical to make the public transport punctual by improving its travel time reliability.

Congestion charges

When too many private vehicles enter some parts of the city, they can create congestion there. Urban planners must identify such areas and impose a congestion charge to deter entry of private vehicles. For example, the congestion charge in London central districts equals the cost of 9 litres of petrol. This encourages people to use public transport to get there.

Car pooling

If people don’t want to give up their vehicles, or if good public transport is not available, they can be nudged to adopt carpooling to reduce the number of cars on the road.

Odd-even days rule

Under the “odd-even” rule, a vehicle with an odd registration number is allowed to ply on city roads only on odd dates, and a vehicle with an even registration number is allowed to ply on city roads only on even dates. Thus, on any given day, only half of the city’s cars can ply on the roads.

Traffic Incident Management

Every once in a while, every road will face some incident that blocks its traffic. For example, a breakdown or accident. There must be a strong strategy to clear up the road in minimum time. This requires a proper towing facility, and a reserved area nearby where the broken down vehicles can be shifted.

Work Zone management

The traffic on the many roads is disrupted for a few days or weeks because of heavy repair work or installation of new infrastructure (pipelines, cables, culverts, metro project, flyovers, underpasses, road widening, white-topping, RCC dividers, etc). Such disruptions can be minimised by various on-site measures such as temporary traffic diversion, temporary signages, hazard-warning lights, lighting at night, safety barriers, etc.

In addition, online measures are also needed, such as notifying all vehicular navigation services, so that the navigation apps can actively divert the traffic away from the affected roads. The ITS must also be fed with this data so that all emergency services can be diverted on alternative routes.

Read more: How commute can be easy, safe during Metro work on Bengaluru’s ORR

Road Infrastructure Management and Congestion Control

The roads and footpaths are designed to carry the required number of vehicles and pedestrians per hour without congestion.

For any given stretch of road, the traffic flow (vehicles/hour), speed (km/hour) and traffic density (vehicles/km) are interrelated, as explained below:

If a stretch of road is empty, a driver can ply his vehicle at a “free-flow” speed. If a few vehicles are added, the traffic flow increases, but now every driver has to moderate his speed because of the other vehicles on the road.

As we add more and more vehicles, the speed gets decreased a little, but the traffic flow increases. However, if the traffic density goes beyond an optimum value, each driver starts facing severe space constraints, and has to slow down disproportionately. As a result, the traffic flow starts decreasing. This is the onset of congestion.

At some point, the traffic becomes unstable (the vehicles have to move in stop-and-go bursts). Although there are a lot of vehicles on the road, they are travelling so slowly that the effective traffic flow rate reduces drastically. Everyone ends up wasting a lot of time on the road, and burning fuel while the vehicle crawls forward or just idles at one spot.

The different travelling conditions are characterised with a parameter called Level of Service (LOS) that describes the traffic flow under given conditions.

In this context, the following text explains the measures required to control congestion:

LOS planning

The geometry of each road is designed to achieve a certain throughput (vehicles per hour) with a certain LOS.

The LOS concept is also applicable to pedestrian traffic (the number of pedestrians on a footpath affects its throughput). Therefore, each footpath also must be designed to carry a specified number of pedestrians with the specified LOS.

LOS control

If the LOS target for road or footpath is not met, corrective actions must be taken, such as clearing encroachments, removing obstacles, widening, etc.

Apart from potholes, a lot of other obstacles appear on the road and footpaths, which reduce their carrying capacity:

Therefore, all the following obstacles must be eliminated systematically:

A. Defects on roads

- Potholes

- Waterlogging on road (due to defective drainage scheme or clogged SWDs)

- Mud on the road (after waterlogging recedes)

- A large stone (drivers keep stones under a tire to prevent rolling down of vehicle)

- A kerbstone that has loosed and fallen on the road

- Mounds of dust (the road cleaners do not pick up dust)

- Loose layer of metal jelly (BBMP just fills up potholes with loose stones)

- Garbage (black spots on the road)

- Open manhole (the cover may be missing, damaged or lying on one side)

- Manhole cover sticking out of the road

- Conduits of telecom companies sticking out of the road

- Electric poles erected on the road

- Ditches cut for pipes and cables

- Uneven patch of asphalt

- Illegal bumps

- Overhead cables that are cut and left on the road

- Vehicle parts that are left on the road after accidents

- Roadkill (animal bodies left on the road)

B. Defects in footpaths

- Missing footpath

- Footpath blocked by a tree, or a man-made structure (transformer, pole, hoarding)

- Drains are fully open, or many slabs are broken or missing

- Footpath has uneven surface (unfit for walking)

- Lighting is missing/inadequate

Road space allocation

Some space has to be allocated to on-street parking (especially for taxis and autos) and street vendors. Such spaces must not affect the target LOS of the roads and footpaths.

Actual congestion data must be collected and reviewed periodically to optimise the roads and footpaths.

Road asset management

Roads are like the veins of our city: Congestion on a road is like a blockage in the veins, making the city sick. For example, Bengaluru city alone incurs an annual loss of ₹ 47,743 crores due to congestion on its roads. This amounts to an annual loss of ₹ 39,000 per head! This loss can be avoided if we treat our roads as precious assets that must be tightly controlled, and used exclusively for transportation.

This calls for an active management of all road assets to prevent any loss of its capacity due to non-transport uses, such as social/religious events, political events (e.g. dharna, rallies) or commercial activities. All such activities must take place strictly in off-street mode. Violators must be punished promptly to discourage misuse of roads.

Road capacity optimisation

Even if all roads are managed well, eventually the traffic worsens, because the city itself keeps evolving constantly. The demography changes, and new residential and commercial zones come up in the city. Thus the travel demand of the population keeps changing in different parts of the city. Our multimodal transportation network must keep up with such changing needs.

This calls for a periodic reassessment of our Travel Demand Model (see Part 2). Based on its conclusion, the multimodal transportation network must be optimised. This includes extending the networks, improving the interchanges between different modes, increasing or reducing trip frequencies, changing routes, etc.

Also read:

- How to make Bengaluru traffic jams go away

- Will congestion pricing help Mumbaikars add an hour and a half to their day?

- Can carpooling become the next big thing in our cities?