Anyone who has visited a government office to obtain certificates or documents is aware of the daunting process it entails. With the aim to cut out long queues of disgruntled visitors, e-sevai centres were launched across the state in 2006 to provide IT enabled-services to the public. This came long before the formulation of the National e-Governance Plan (NeGP).

Despite the pioneering move, government-run e-sevai centres in Chennai face myriad issues that prevent their effective functioning.

Working of public and private e-sevai centres in Chennai

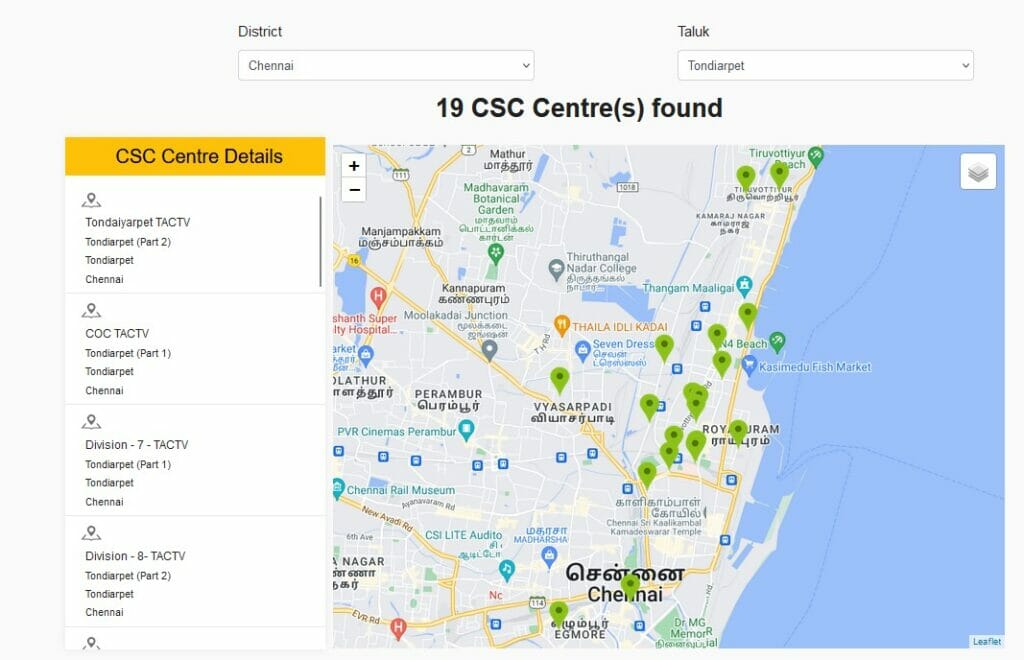

According to the Tamil Nadu e-governance agency, around 92 different kinds of services are provided at the e-sevai centres in Chennai and elsewhere. The centres in Chennai can be located here. These public centres are usually attached to the government offices like the Taluk offices where the public can easily access the service.

There has been huge demand from the public to access services offered by the e-sevai centres such as procurement of community and nativity certificates, services related to the linkage of Aadhar and updation of information on government documents.

The government identified a need to augment the capacity by roping in private players such as browsing centres to expand the scope of e-governance. The rationale was that the private players will be able to offer services beyond the working hours of the government-run e-sevai centres and ensure that the services can reach more citizens.

The private e-sevai centres have to go through an application process that involves paperwork and verification, including police verification, to be able to operate the centre. The private e-sevai centres may be standalone centres or they could also be attached to businesses that provide other services such as browsing centres.

In recent years, poor delivery of services and policy decisions by the government have contributed to the public opting to avail services from the private e-sevai centres over government-run centres.

Read more: All you want to know about e-sevai centres

Issues faced by users of e-sevai centres in Chennai

Ramani S, a resident of Mylapore, says that he prefers to use the privately run e-sevai centres in Chennai even if it means that he has to pay extra.

“The work gets done much faster than the public centres. The operators in the public e-sevai centres are unapproachable. I visited the public centres a couple of times to get some certificates and they asked me to come later as they were on a break. When I went later, the place was more crowded and I was given a token. I had to wait for more than an hour. Whereas when I visited the private centre, there was no crowd and I also got my work done easily,” he says.

Suvetha S, a resident of Ennore, says that the public e-sevai centre in her locality does not have sufficient facilities.

“There were server problems when I visited the place. There were a couple of other private centres nearby and I got my work done from those centres,” she says.

She also adds that when the application seeking a certificate got rejected at the private centre, the private operators asked her to approach the government office. She ended up paying the fee at the private centre for processing the application and also had to make multiple visits to the government office, defeating the purpose of having online services.

Notably, many residents are unaware of the services provided in the e-sevai centres and think that the centres provide only certificates.

There is also the issue of over-charging at public e-sevai centres.

Kamesh R, a student, approached the government-run e-sevai centre in Chennai’s Royapuram to get income and community certificates. He was asked to pay Rs 250 per certificate by the operator. Since there was no display of the prices for each service, Kamesh paid Rs 500. He later found out that he was over-charged.

“Had I been to the government offices to collect certificates physically, I am sure that they would have demanded a bribe of thousands of rupees. I was in need of the certificates and that was my concern at that hour,” he says.

Issues faced by operators of e-sevai centres in Chennai

While the people are dissatisfied with the services provided at the public e-sevai centres in Chennai, the operators who work at these centres have their own set of issues.

Sivakumar*, a data entry operator in an e-sevai centre in Chennai, expresses dissatisfaction with the pay received by operators at public e-sevai centres. He says that the e-sevai services are an additional income for the private centres. They are often attached to another business and do not depend on it for their income.

“However, this is our full-time job. The data entry operators in the public e-sevai centres in Chennai are employed on a contract basis and get paid around Rs 8,500 per month now. This includes the amounts deducted for ESI and PF,” he says.

Kathiravan*, a data entry operator in an e-sevai centre in Chennai, says, “Since neither the contractors nor the administration provides the basic material for work like the printing papers or toners used in the printers, the operators or the public end up bearing the cost of it. When the operators bear such costs, it goes from their salary, which is already a very meagre amount.”

Further, Kathiravan points out that, unlike any other government office, the operators in the public e-sevai centres in Chennai and across Tamil Nadu have to register their biometric attendance five times a day.

“If we fail to do so, our pay for the day will be cut. Even if there is any technical issue in registering the thumb impressions, it will reflect on our attendance. Often, we end up with pay cuts due to technical issues beyond our control” he says.

The operators at these centres also note that they were not provided with any training on the operation of the e-sevai centres. “We were given an orientation on the joining day and no other instruction was conveyed to us.”

Since these workers fall under the skilled worker category, they demand the minimum wages accordingly. They also demand the terms of the contract be made transparent.

In contrast to these grievances, those who run e-sevai centres in their private capacity face little issues.

Selvam R, who runs a private e-sevai centre alongside his stationery and mobile shop, says that the service centre is not his only source of revenue. “However, even if five people come to the shop for accessing any kind of services, I earn anywhere between Rs 1,200 to Rs 1,500. I charge a minimum of Rs 250 for processing one certificate.”

Read more: How can you get your community certificate in Chennai?

Revamping public e-sevai centres

KC Gopikumar, State Secretary Centre of Indian Trade Unions, (CITU) points out that the government has been making moves to shut down public e-sevai centres and privatise the services.

“Citing that there is no sufficient revenue generation from the centres, the government is closing a few public centres. In 2021, around 96 public centres were closed. Of this 66 were located in Chennai. Not every day would a person require an income certificate or a community certificate. Following the protests from the operators, the government changed the term to ‘merging the centres’ instead of ‘closing’ them. We have now taken up the case to the Madras High Court,” he says, adding that it is a public service but the government’s focus is on generating revenue.

When the number of e-sevai centres is reduced, it will affect the public in two ways.

“One – it will lead to job loss for thousands of data entry operators. Two – when such public centres are closed, the public will start approaching the private centres where the service is turned into a commodity. For instance, if one can get a birth certificate for Rs 20 in a public e-sevai centre in Chennai, the same will cost Rs 200 in a private centre and the government is not taking any measures to regularise this,” says Gopikumar.

“While the government states that the public can access the services through the citizen portals available online in the respective department’s web portals. Not all the people have access to those portals and not all the people have the knowledge on how to access those services,” says Gopikumar.

Data security is yet another major issue in letting private e-sevai centres handle the personal data of the people. There is no mechanism to protect such data. The checks and balances to prevent misuse of data are non-existent.

“If I demand a bogus community certificate citing that I come from a scheduled caste or a backward caste, I can get it in the private e-sevai centre. This can be obtained without any government authorisation. This is yet another dangerous aspect of privatising such services,” says Gopikumar.

“TNeGA has obtained field-level understandings of selected districts, collaborated with e-District Managers, and collected feedback from citizens to ensure that the planned new e-sevai centres will resolve all identified deficiencies. For this, it has established a more robust feedback system, a rebranded identity for increased visibility, and well-planned training programs for operators with consistent monitoring and evaluation,” says Ra. Shhiva, Lawyer and Director, Indus Action, an NGO working closely with the department to translate field-level evidence into policy.

Going forward, operations of e-sevai centres old and new must be revamped to ensure that the public who access the services have a seamless experience and that the operators also receive fair remuneration and better working conditions.