The usually busy junctions on Mount Road and OMR wear a deserted look. Almost two months into the nationwide lockdown to curb the spread of the virus, most vehicles have been off the streets, with only emergency travel and essential services permitted in Chennai. The spread of coronavirus has altered, at least for the near future, how we commute and the kind of travel we consider essential.

While the pandemic’s implications for health have prompted extraordinary precautions, the economic impact of these measures have been devastating for many, even in the short-term. One section of people adversely affected by this have been auto and taxi drivers who are part of the gig economy. With most of their regular customers working from home or forced to stay indoors amid government restrictions on commute, many have not had any income for close to two months.

“When you say the virus came from abroad, one of the first people those returnees make contact with are cab drivers, who have been largely ignored in discussions about its impact,” says Jude Mathew of Independent Taxi Drivers and Owners Association.

Crisis in waiting

The precariousness of the gig economy has been apparent for many drivers for some time now. The attractive packages that once lured them to take the job up full time, purchase cars on loan and even move to Chennai for a living, have all but dried up in the recent past.

“The situation has been steadily deteriorating over the last few years. The commissions we have to pay have increased, and the incentive structure that once looked so promising has not brought much supplementary income. Most drivers were working for close to 12 hours a day to merely make ends meet even before the pandemic. We have staged protests to demand better outcome for the drivers, but not much has changed. Now things have become worse,” says Prashanth, a cab driver with Ola.

Though the lockdown was formally announced on March 25th, many firms opted to work from home starting almost a month before that. Income of drivers plying autos and cabs for Ola and Uber dried up right from the beginning of March.

“I used to make Rs 800 or so a day, but as the coronavirus scare appeared, income dropped to Rs 250 – Rs 300 as more people started to work from home. As early as that, I got worried about what would happen in the coming months,” says Sakthi* an auto driver with Uber.

Funds for driver-partners

At the start of the pandemic, when grounding their fleet became a reality, Ola and Uber announced measures to aid their drivers:

“Ola has taken several initiatives to support the driver community which include financial support through Sahyog loans, which is an interest-free credit, and waiving lease rentals. Ola’s driver-partners have access to free doctor consultation for themselves and their families. Drivers and their families also get a provision of essential supplies and medical emergencies through the ‘Drive the Driver Fund’, a crowd-sourcing initiative by Ola Foundation. Ola is looking to raise a sum of INR 50cr towards this long-term contingency fund with the company and its employees having committed a sum of INR 20cr towards the fund over the year.“

Official statement from Ola Cabs

On their efforts, a spokesperson from Uber said:

“To help drivers during the COVID-19 pandemic, we created the Uber Care Driver Fund, with an initial commitment of INR 25 crores from Uber. Over the last two weeks, we have disbursed grants to more than 75,000 drivers. As Uber raises additional money, we’ll continue to distribute grants to as many drivers as we can, as quickly as possible..Other forms of our support to drivers during these challenging times include a waiver of lease rentals, facilitating EMI relief, rolling out an additional insurance policy and offering drivers access to online medical services, such as DocsApp, at no charge.“

Assistance arbitrary

Almost two months into the lockdown, the number of drivers who have benefitted from these schemes, out of those who drive regularly for Ola and Uber, has been very few, based on accounts from online and offline groups that the drivers are part of.

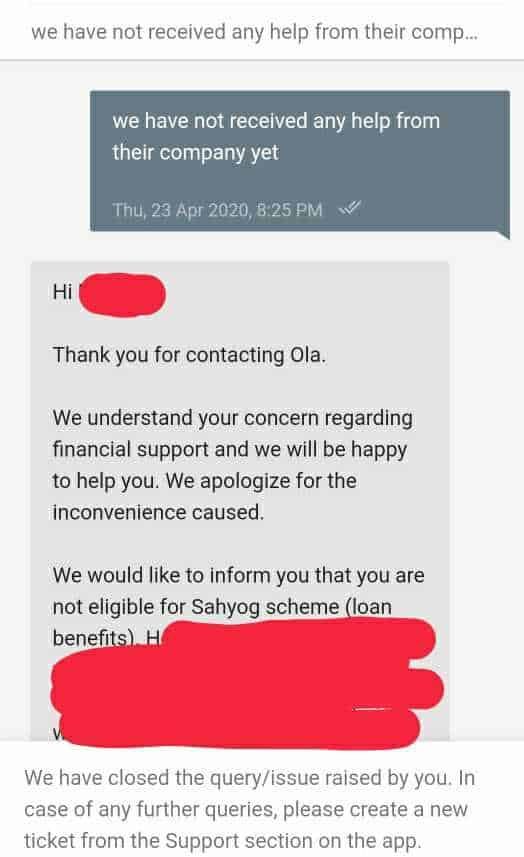

“I reached out repeatedly to Ola for support. I emailed the company for a response but was told I was not eligible for the Sahyog scheme. The eligibility criteria has not been made clear. In my network of drivers, we have had 3-4 people who got the loan but the rest have been left in the lurch,” says Ramesh, a cab driver with Ola.

Our efforts to get a clear, unambiguous communication from Ola authorities on what makes a driver eligible for the Sahyog scheme failed to bring forth any response.

A similar sentiment is echoed by other drivers who feel that the firms should provide blanket assistance for all. “We have all been paying commissions monthly to companies like Ola and Uber for driving with them. But when it comes to providing relief, they have set some conditions,” says Subramanian D of Udhavum Karangal Drivers Association, “Such times call for unconditional support to all their drivers who create wealth for them. Instead they are keen on getting publicity by helping a few people and marketing that as their good work while most drivers are struggling to make ends meet. If these companies can donate to the government fund, they should also be able to help their own drivers first.”

On what he has received so far, Prashanth said, “At the start, I was hoping Ola would credit some amount but no such scheme has reached me. I was provided with some rations from the driver fund of Ola but that was just barely enough to feed my family for a week.”

Sadiq Jaffer, a cab driver with Uber, is among the few who was assisted by the company. “Two weeks into the lockdown, I got a call asking for my approval to credit my bank account with Rs. 3000. Once I consented, the amount was credited. I was told that this amount need not be paid back. It has been helpful to tide over a time when we cannot make any money.”

Ola, in its statement to Citizen Matters, highlighted the case of a driver, Rajesh Kumar of Kolathur receiving financial assistance of Rs 58,000 for the hospital bills for the birth of his child.

Neither Ola nor Uber clarified what criteria was used to determine which of their drivers are eligible to qualify for aid disbursed, and when.

“If these companies can donate to the government fund, they should also be able to help their own drivers first.”

Member, Udhavum Karangal Drivers Association

Getting by with little

In the absence of financial aid many drivers turned to close family and friends or the community. “As soon as the lockdown began, all income stopped. I could not sustain myself in Chennai. So I had to return to Cuddalore. My family has been getting by through help from relatives but we have had no calls or support from Ola. I have been driving for them for three years,” says Karthik*.

Many drivers shared similar testimonies. Mani, a driver with Uber, has been borrowing from neighbours to get by. “I have been with Uber for nine months exclusively and driving the auto for them. But since the lockdown we have had no word from them. My elderly parents are receiving money from my brother as I cannot contribute. The only message I have received from them is to stay home and stay safe.”

Slipping through the cracks

The informal nature of the gig economy prevents the drivers from receiving other forms of assistance such as government schemes. The Tamil Nadu government announced grants of Rs 1000 and 15 kilo rice, 1 kilo dal and 1 litre cooking oil to all drivers who are registered with the Tamil Nadu Autorickshaw and Taxi Drivers’ Welfare Board. But according to accounts, only around 83,500 among all drivers other than state govt bus drivers (includes autowalas and cabbies not affiliated to Ola/Uber) — are registered with the welfare board.

“The government aid has also not reached many of us, as most are not registered with the welfare board. This should be made mandatory when issuing a transport license, so that no one misses out. Even now, the government has our information on their file and can expand the net to include more families of drivers under the relief scheme, but they are not willing to do so,” says Jude.

There have been attempts to organise and demand better working conditions and to prevent further turmoil for the drivers. “Companies like Ola and Uber have the technology. We have made attempts to break away and make our own app, as that’s the infrastructure needed for us to carry on our work without giving away so much of our earning as commission to them,” says Subramanian. An app called UK Taxi was piloted among close to 1000 drivers in an attempt to wean away from Ola and Uber.

“We have been trying to negotiate for better conditions for drivers. In a pandemic like this, the travel and transport industry will be the worst hit for a long time. We will have to alter the way we function. The drivers need the government to intervene. We have many petitions regarding driver’s welfare, measures that have been enforced in states like Karnataka, pending before the transport department,” says Jude.

Though the drivers are unhappy with Ola and Uber’s handling of the crisis and the apathy shown by the government, many don’t have an option but to return to work when the lockdown is lifted.

Having only finished Class 12, Mani doesn’t see many options left for him except as a driver. “I don’t want to continue doing this work but I don’t have any other job prospects. I know how to drive and I will have to go back once the lockdown is lifted, despite how we have been treated.”

“The companies don’t care if the drivers and their families are starving or alive, but with every review of the lockdown, we received calls from them on whether we would be able to return to work if the lockdown is lifted,” laments Ramesh.