While Bengaluru’s tree-lined streets are getting fewer and fewer, it is becoming evident that the concrete infrastructure has come at a price.

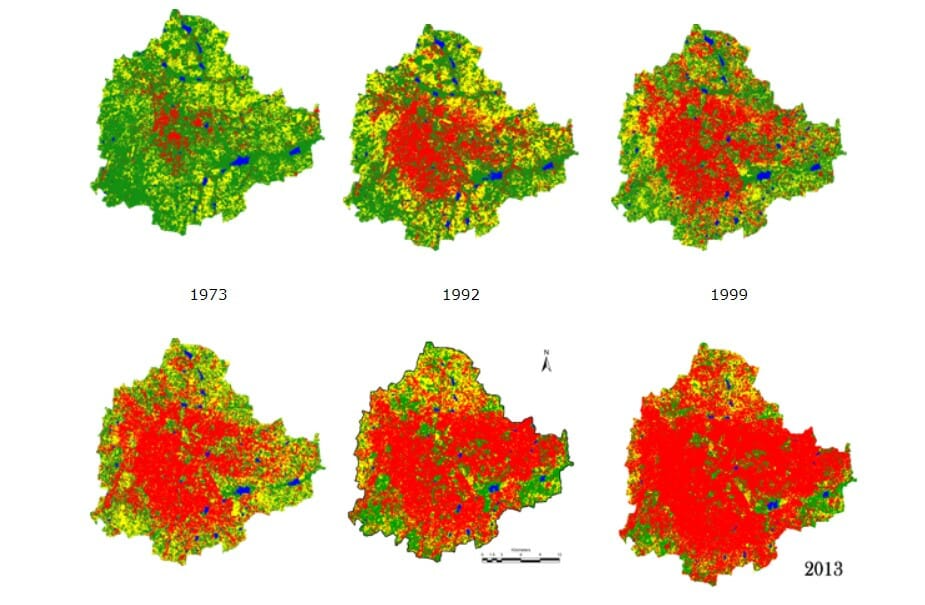

Several reports have attested to the decreasing green cover in urban areas. According to the State of Forest Report 2021, only 3.91% of Karnataka’s geographical area has tree cover. The data also revealed that between 2011 and 2021, Bengaluru lost almost 12.9 square kilometres of moderately dense forest.

“Tree cutting is presented as inevitable or as a fait accompli for any road or metro project. More often than not, how the road should progress is decided first and all trees in the path are removed, rather than exploring if there could be small deviations made in the alignment that could protect some old trees,” says Seema Mundoli, faculty at School of Development at Azim Premji University.

Scope of threat

While Citizen Matters has reported on how road-widening and infrastructure projects pose an obvious and very evident threat to the green cover, they aren’t the only culprits.

A recent study titled Climate change increases global risk to urban forests, assessed the vulnerability of tree species in Delhi and Bengaluru to climate risk. The authors found that both cities were slated to get warmer and trees in both regions are experiencing stressful conditions that impact their health.

“For India, we assessed 43 and 76 tree species in New Delhi and Bengaluru, respectively. Both regions will witness a decrease in annual precipitation by 2050, which will imply a myriad of consequences for the species,” says Manuel Esperon-Rodriguez, one of the study’s authors.

“Some of the most common signs of poor tree health are wilting, bare patches, broken branches, leaf-free branches, abnormal leaf colour, shape, and size, cavities, cracks and holes in the trunk or limbs, holes in leaves, visible insects or insect evidence, and other pathogens,” he says.

“A tree that loses its leaves or has canopy dieback stops providing shade and is not capable of providing other cooling benefits for the residents. These unhealthy trees might require additional management that increases costs and represents a loss for governments. In extreme cases, trees might need to be removed if they become a hazard,” he adds.

Esperon-Rodriguez, who is also a research Support Program Fellow at Western Sydney University, says that the frequency at which trees have begun experiencing climate stress has seen an uptick.

“In Bengaluru, 70% of the species are potentially experiencing stressful conditions for mean annual temperature, and these figures will potentially increase to 88% by 2050,” warns Esperon-Rodriguez. While some species benefit from certain changes in climate, especially for increases in rainfall, it wasn’t the case for Indian cities.

Urban trees: A necessity

Having outlined the threat, we need to realise the importance of trees in the urban ecosystem, especially for a city like Bengaluru. “Trees help to settle the dust, an increasing problem in Bengaluru where there is always construction activity and vehicular pollution is also churning up road dust,” says Seema.

Read more: Want to plant a tree?

While trees sequester carbon, helping reduce greenhouse gas emissions, she adds that the surface of leaves, depending on the tree species, absorb sulphur and nitrogen oxides at varying levels thereby mitigating the impacts of pollution from vehicles and industries situated in cities.

“They also cool cities. The road surface temperatures under the shade of a tree can be 20-25 degrees celsius lower than where there is no shade,” says Seema. Research has shown that green infrastructure enables air pollution abatement and stormwater management, which Bengaluru is failing at.

Illustrating the need for climate-resilient forests, Esperon-Rodriguez explains how these are made up of tree species that can cope with and face climatic changes as they occur. “We need species that are capable of thriving and surviving. What we want to tell governments through this data is that we need to start making very mindful decisions about what we are planting, so the trees we plant today will survive the next 20-50 years,” he says.

Read more: Making Turahalli a model for urban forests

Scope for urban planners

According to Esperon-Rodriguez, urban forests are made up of trees that can withstand the impacts of climate change and can be artificially engineered through planning. “Cities can assess species that are coping well with changing climate and introduce them to the urban ecosystem with caution.”

On the topic of effective tree management, Seema says that Master plans have mentioned tree planting. “The Revised Master Plan 2015 had a rule that builders will have to plant a tree for a certain area of land and only then will they be given occupancy certificates,” she clarifies. Tree planting is mentioned in the plan, and it says: “Planting a minimum of one tree is mandatory for a site measuring more than 2,400 square feet and a minimum of two trees for a site measuring more than 4000 square feet.” It does not mention other tree management or planting mechanisms by the state.

On effective planting mechanisms that are climate-resilient, Esperon-Rodriguez suggests the authorities find species that are capable of performing and remaining healthy during periods of extreme heat. “The best conservation is ensuring the trees planted have access to enough rich resources in the first critical years of their life, to ensure their survivability.”

He also mentions how it should not just be the government taking action, but the local communities also have to be involved to understand the importance of urban forests. “This is very important because sometimes the government may not have the resources to take care of street trees that are planted, but those who live nearby can act as its caretakers,” he adds.

The study can be accessed here: Esperon-Rodriguez, M., Tjoelker, M.G., Lenoir, J. et al. Climate change increases the global risk to urban forests. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 950–955 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01465-8