As the world has become predominantly urban, with the impact of climate change being experienced worldwide, protecting forests everywhere, particularly close to urban areas, is critical.

Forests, especially those near cities, serve in regulating local temperatures, cycling water and nutrients, as repositories of biodiversity, and as a critical resource for the sustenance of rural, pastoral and forest dependent communities. Forests are also sacred spaces for communities that continue to revere shrines inside such spaces.

Understanding the nature and composition of the forests, the community dependencies on them and the legal provisions that protect them is central to protect such forests for posterity.

In the age of urbanisation, protecting forests (now called urban forests as their surrounding rural landscapes have been urbanised) must be at the core of long term strategic plans of cities. That is, if protecting biodiversity and keeping the city and national commitments to the Paris Climate Agreement have to make real sense.

Read more: Why has the ‘tree park’ plan in Turahalli forest irked Bengaluru?

Colonial legacy

Forests have been around. It is cities that are encroaching into such critical natural spaces. Precolonial history reveals India’s forest cover was extensive and human settlements were interspersed across forested areas.

There are also innumerable examples of how forest protection was not a centralised effort. Instead, it was an outcome of a deep ethos of respecting nature, based on an intricate relationship with it. There also are examples of how forest protection was secured through a range of innovative practices respectful of nature’s limits.

Through the colonial times however, laws that territorialised forests evolved, pushing out forest dependent communities, even criminalising them. The same set of laws continued in the post-independent period, barring rare exceptions, such as through the Forest Rights Act 2006. This law rightly places forest protection as part of a community enterprise. In Independent India, the Forest Department, an institution steeped in colonial forest laws, controls forests as though it is its territory.

Even so, within the existing laws there are rules and regulations that can be adapted by urban communities to protect and wisely use forests in urban areas. While there is a need to create more lung spaces for ever expanding cities, it is critical to appreciate that the ecological services that forests and other such natural resources provide must not be substantially altered. For, the consequences will be devastating and cities will die.

Life-blood for cities

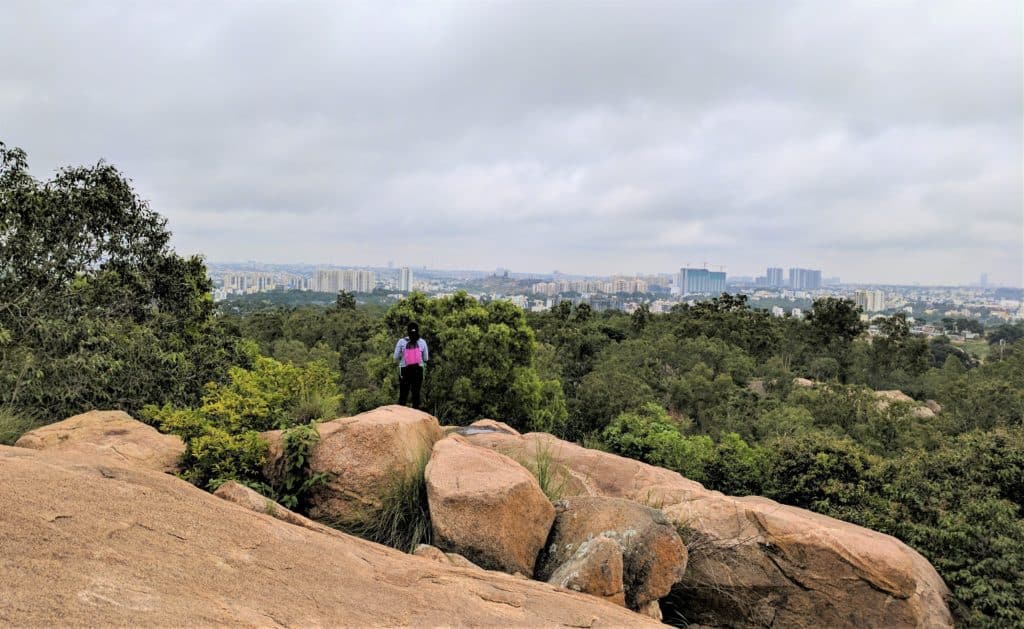

It is extremely important that forests that survive in urbanised settings are protected, as they exhibit distinctive features suitable to the local geography and serve as local climate regulator, act as a sponge in absorbing rainwater and as habitats to a range of flora and fauna endemic to the region.

Read more: Unchecked tree loss is wiping out the Slender Loris from Bengaluru

What urban residents rarely acknowledge is that such forested spaces provide roosting and feeding zones for a variety of migratory birds that make long journeys north and south of the equator.

Urban forests are a living biology lab, a natural history library, a space for experiential learning, a place for finding calm, all of which are critical for present generations to appreciate so the next generation can benefit from their stewardship.

In this context, the proposal of a tree park at Turahalli Minor Forest, to the south of Bengaluru, resulted in heated discussions and debates. The idea is to invest in strengthening of walking paths inside the forest, whilst also providing a variety of recreational facilities – such as a gym, a yoga centre, children’s play areas, etc.

The unnatural state

The Karnataka Forest Department claims with particular pride that it has created 132 such tree parks across the State, and more are in demand from various MLAs.

Read more: Tree park beda okay, but what’s the vision for Turahalli?

The Indian Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change has backed such tree parks as part of urban forestry, first in 2015, and then again in 2020 as “Nagar Van Scheme“. Indian Environment Minister Prakash Javadekar has also encouraged the utilisation of CAMPA funds for such projects. Besides, there has been the aggressive promotion of corporate engagement in such projects through CSR.

It makes perfect sense to create tree parks as ecological restoration projects from mines, land-fills and abandoned industrial sites after decontamination. But to create a tree park in a natural forest, such as Turahalli, belies logic and is also against the laws of the country.

Read more: Turahalli: Missing the woods for the trees

It must be appreciated that once a natural forest is turned into a ‘tree park’ and activities focused on providing recreational spaces are promoted, it will bring in investments that will pour cement, steel, glass, granite, tiles and more into such verdant and wild spaces.

Contrast this with the possibility of bringing urbanised communities, distanced as they are over decades, even generations, from the wild, with unnecessary mortal fears of everything wild, and then bringing them to be comfortable with such wild spaces.

Would we rather have a ‘green space’ that is manicured with exotic plants that guzzle water and pesticides, and paved pathways with no scope for even ants and insects to live!

Tapping collective wisdom

It’s the imagination that needs to change so that the original forest ecosystem finds a place in our urbanised living. Then, at both the local level and higher echelons of power, the capacity of forests as a salve to our stressful lives, while also serving as pollution sinks and water recharge zones, and as hubs of biodiversity will begin to flower.

Bengaluru has numerous research institutions and environmental organisations which are willing to collate such imaginaries and help conserve Turahalli and such other wild spaces for the benefit of present and future generations.

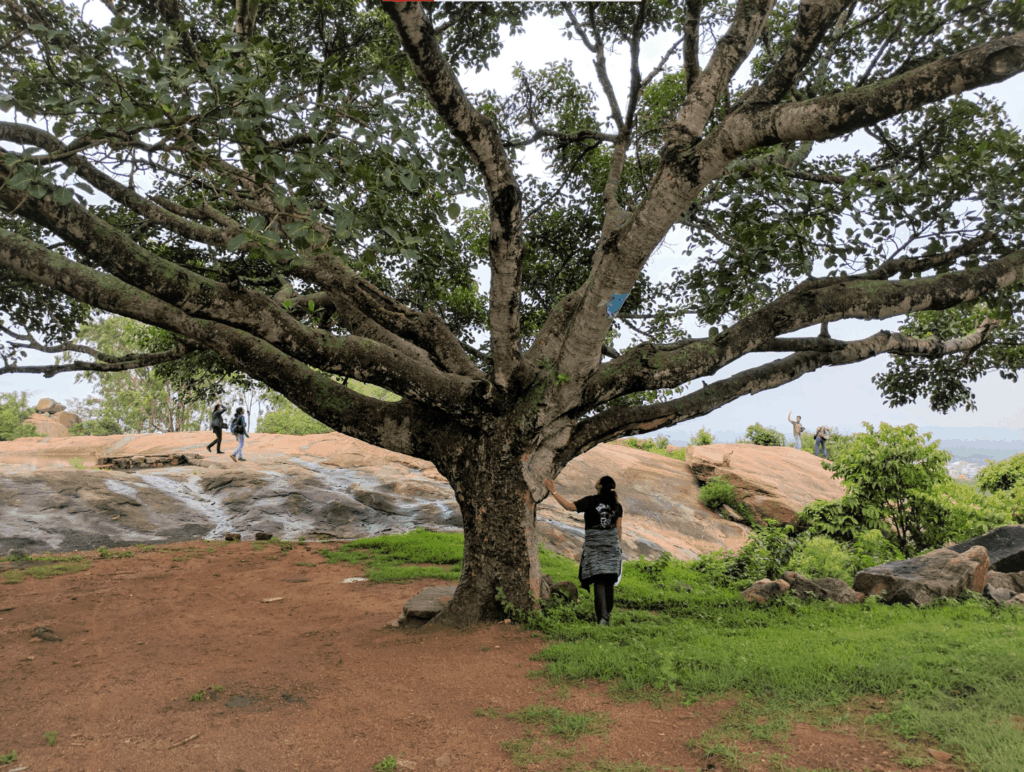

The city’s positive scientific temperament has nurtured hundreds of ornithologists, botanists, butterfly experts, naturalists, ant experts and more. Besides, in spaces like Turahalli, the natural instinct of humans to climb rocks has been nurtured, with hundreds who practised here scaling impossible peaks across the Himalayas.

It is in these forest patches that an adventurous zeal and natural curiosity of so many ‘experts’ of today has been nurtured. A variety of studies are a testament to this human endeavour.

Protecting urban forest patches requires careful analysis of the situation. We ought to ensure that local ecology is protected and maintained with minimal alterations. And that has to be based on the active involvement of local communities, naturalists, arborists, ornithologists, insect experts, herpetologists and a range of others.

Read more: Body to protect Bengaluru’s biodiversity revived, but can it help?

Besides, Turahalli offers an excellent opportunity to engage Area Sabhas, Ward Committees, Metropolitan Planning Committees, Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike, the Forest Department, State Finance Commission and various agencies of the State Government. They can come together to conceptualise a ‘wise use’ plan that allows for all the uses particular to the forest, as necessitated by the Public Trust Doctrine. This doctrine has been repeatedly upheld by the Supreme Court and Karnataka High Court.

To turn a forest into a tree park would mean that the forest department operates as a municipality whose role is to make parks. Also, it will be advancing a non-forest activity in a forest area.

The prevailing contestations over Turahalli and such forest patches is an incredible opportunity to set right the governance of such spaces so that such green havens continue to survive despite concretised and noisy cities.

It would be a beautiful gift to ourselves and to the future that we can occasionally traverse through a wild space, wonder at birds we chance upon, catch a breath of fresh air, sit quietly on a rock to reflect in the serenity of the forest to find the calm within, or also just learn to boulder up a rock and discover the confidence and self-esteem that is so essential in our stress filled lives.

Turahalli is one such amazing landscape that provides all of these possibilities, and right in the backyard of south Bengaluru.

>> It would be a beautiful gift to ourselves and to the future that we can occasionally traverse through a wild space, wonder at birds we chance upon, catch a breath of fresh air, sit quietly on a rock to reflect in the serenity of the forest to find the calm within, or also just learn to boulder up a rock and discover the confidence and self-esteem that is so essential in our stress filled lives.

>>

I just wished this wish comes true!!

It is still happening around – beyond city limits (not sure why we seem to running out of petrol when we reach Turahalli Forest 😉 )

Its only at the core of concretized jungles that people don’t find such places. It is a choice that we as a society have made in slowly but surely concretizing every green space. It is here that we have to create more of such green spaces, so that we don’t feel deprived and search desperately to find them. When we find places like Turahalli, we lose our sense of discretion between a Park, a Tree Park and a Forest.

We have to create such places (eg a Miyawaki forest) all around if we really value the healing power of nature.

We need to realise the ground realities of the present situation in and around Turahalli Forest. Without it, using this forest – will only end up in disaster.

——————–

Bhargavi, going through your other 6 posts – it has a very rich background analysis of every topic you have written about. While you have cared about street vendors and pedestrians and all the voiceless people… here you have totally missed the beings (either speechless or who’s language we don’t understand) – Turahalli is a forest without any voice!

> Making Turahalli a model for urban forests

Why should we limit our thinking again teaching people how to use the forest, but why can’t we think – can this forest be a sacred space… where how to worship nature in the true sense can be communicated in silence.

——

Why should anybody work only for a few to get access in this specific forest to shine at the national and international level?

The ground reality is that these efforts in getting access to these few affiliated ones who can afford these activities… will only give room for many more to demand their way. Nothing wrong in supporting these few activities, but here, dear Bhargavi, we fail completely by not supporting the rest! Who are equally lawfully (created by we the human beings) are supposed to enjoy and heal themselves in nature! Dear Bhargavi, don’t you think we are taking away the rights of many others who want access into the forest and have their way? Among these – there were few who wanted to sell tea and chips too. Why should they be kept out of the forest? Why a different rule for them?

——

But have we ever thought of the awareness among the people who will enter this supposed to be sacred place? Basically what can be done or should not be done (eg littering, playing music, smoking & drinking, cooking, screaming, etc) in a forest. Eg a very literate sophisticated parent was once teaching her child by shouting out the spelling of S-E-V-E-N. There are many such examples.

Who will work on this? Where should we start working?

At Turahalli forest? At cost of the forest beings? Or, wherever we are?

I do teach science experiments to children….

And when it comes to experiments related to magnets….I ask them to experience this magical/experiential science that is right in their hand and feel that wonder but….

…it’s impossible!!

They end up saying all that is heard and read! North pole, South pole, attraction, repulsion, and all toys and devices where magnets are used!

Same way!!!

Hardly anybody has the time and patience to understand… what this forest is all about!!!

It is very difficult to not see from a utilitarian perspective. But from a perspective that connects human beings back to nature, which we all were once upon a time a part of. Why it is so difficult to see and feel

Turahalli forest is living and growing among us.

The discussion in one of the Zoom calls about Turahalli from a few weeks ago was that “the rich find a way to access wilderness through resorts in national parks. Strangely, this individual was also advocating a complete closure of Turahalli – which it could be argued is a refuge for the poorer man to access natural and wilderness spaces.

While we talk of responsible access, limited access, no access – without any real results on ground, the forest department in its infinite wisdom has already created a class of individuals who will have “privileged access”.

A recent couple of events that I was personally privy to over the last 2-3 weeks demonstrate this. The first was on a Sunday a couple of weekends ago, as I drove past the Turahalli main gate, on the Shobha Apartment side of the forest. A red Wagon R vehicle drove out of the forest, through the gate and down Vajrahalli road. As I drove up I noticed the guard locking the gate behind this vehicle – he had apparently been its escort – I asked him if access had been resumed, he said “no”. I asked about the red vehicle – he grinned sheepishly and shrugged his shoulders.

A one off I thought.

Then again, this past weekend, an acquaintance posted pictures with his family from inside Turahalli forest. Obviously, I was intrigued. Upon messaging this person, it was explained that his father – a well connected man – had facilitated the access via his good offices with local politicians and the forest department. They got an all access guided tour of the forest, as the rest of us sit with our placards trying to arrive at a solution.

I would request all parties involved to submit a comprehensive access proposal to the forest department that makes this whole access issue more democratic. Those demanding stoppage of all access, I request you to see sense in backing access because the ONLY thing you are doing by demanding the blocking of all access is narrowing down the class of persons who are able to access this space. The privileged are still getting in. Everyone else is still getting shortchanged. The forest is open for neither educative nor conservation related efforts. All it is open for is for the rich and fortunate to be able to drive inside it and for those with well connected families to have unfettered and discretionary access. What was a democratic forest is now a glorified golf club.