As students of biology and sustainability, we believe that the government was right in abandoning plans of converting a natural forest into a constructed tree park. The following article details our thoughts on the same.

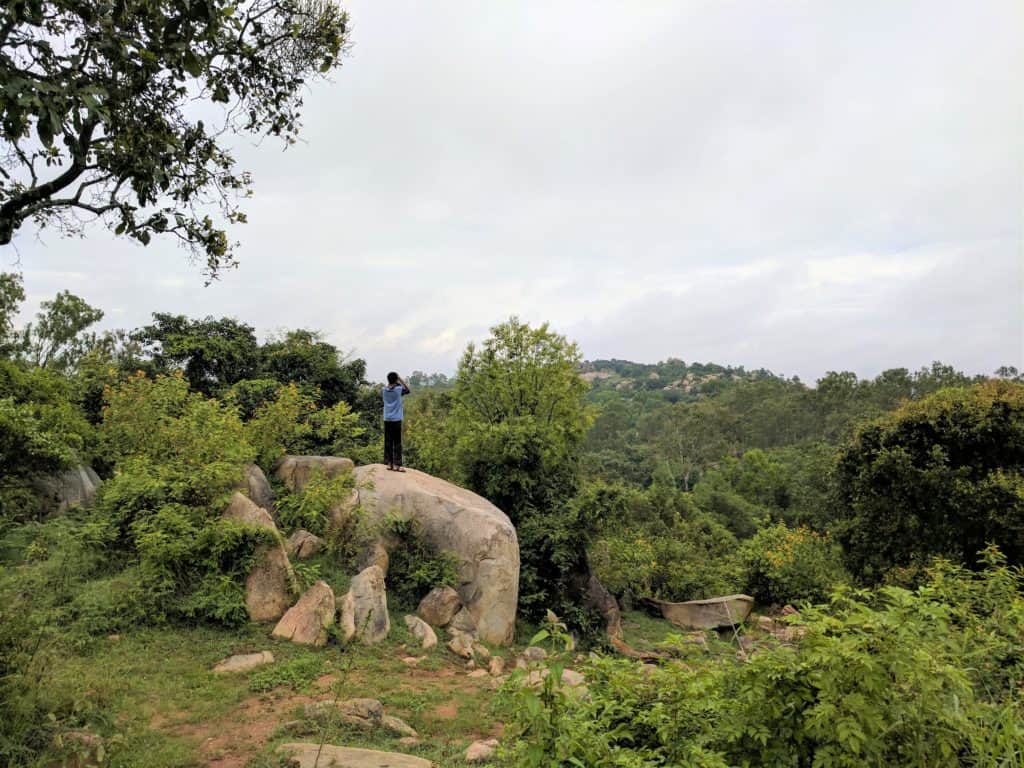

The Turahalli forest that encompasses close to 600 acres of dry decidious forests off Kanakapura road, is a critical ecological space for Bengaluru.

In late 2020, the Chief Minister of Karnataka unveiled the Bengaluru Mission 2022, which aims to improve the city’s infrastructure to support the growing population and also restore Bengaluru’s former glory as the “Garden City”. As part of this mission, the government proposed to create three mega tree parks, spanning 400 acres each.

Towards the end of January 2021, the residents around Turahalli were shocked to see earthmovers clearing the forest, with no prior notice. Upon further enquiry, they learnt that this was for the construction of a tree park. But as a result of strong opposition from locals supported by citizens across the city, the government decided not to go ahead with the tree park.

Read more: Why has the ‘tree park’ plan in Turahalli forest irked Bengaluru?

The aim of the tree park within the Bengaluru Mission 2022 project was to increase both the green cover in the city, and also accessibility to green areas for city residents. Thus, it seems strange, to say the least, to set up a tree park where a forest already existed.

A green connect

Growing up, we and many Bengalureans have fond memories attached to nature in the city. Our exposure to these spaces has allowed us to build a crucial connection with nature. This is important as it allows us to understand the necessity and purpose of green spaces within congested cities and appreciate greenery in its natural state.

Further, nature provides many health benefits (physical and mental) for all of us living in urban areas, serving as an escape from the noise, pollution and crowds of cities.

But nature in cities also has to be equitably accessible. The proposition to have a ticketed entrance to the Turahalli tree park creates a mental, if not a physical barrier. Ticketed entry creates an unnecessary disparity making nature out of reach for those who cannot afford to pay to access it.

Further, the area is known for its popularity among avid rock climbers, fitness enthusiasts, bird watchers and nature lovers. The creation of an enclosed tree park could reduce the spaces available to pursue these interests.

Read more: Turahalli: Missing the woods for the trees

Jungle in a concrete jungle

Unlike a forest, a tree park is not ecologically sustainable—the latter would only be an ornamental space lacking the forest’s thriving natural biodiversity. Introducing new plant species, and changing the environment to include concrete structures would dramatically change the ecosystem.

Turahalli forest is home to biodiversity of different kinds, all of which have their own purpose within the ecosystem. The flora includes a wide variety of flowering vegetation, the most common being the dye-fig tree (Ficus tinctoria), a food source for birds, and Byttneria herbacea, a herb that beetle species prefer.

The Karnataka Forest Department and several well-known naturalists have even organized bird-watching walks in and around Turahalli. Over 124 bird species are dependent on forest, and the deforestation and construction, if the tree park were to be built, would eradicate a large proportion of the habitats of tree-dwelling and ground-nesting birds.

At present the residents in Turahalli view the forest as a comforting natural space. Creating a tree park that disturbs its biodiversity, could also result in conflict. For example, snakes could enter residential areas as their habitat is disturbed.

Read more: Unchecked tree loss is wiping out the Slender Loris from Bengaluru

A range of other ecological benefits too will be lost. The simple act of concretisation not only reduces green cover, but also the cooling effect that trees naturally provide through transpiration. Built areas result in increasing the temperature of the surrounding area. Concretising soil surfaces blocks a large amount of water from seeping into the soil, drastically reducing groundwater recharge.

Since Bengaluru, and especially the peripheral areas where the forest is situated, are partially dependent on groundwater for daily use, this worsens the water crisis the city is currently facing.

Not a patch on nature

History has shown that many a time, when humans try to change natural ecosystems, the consequences are catastrophic. We have seen it with the conversion and encroachment of lakes that have caused flooding in the city.

Thus, we are glad that construction of the park has been halted. When we envision nature in cities, our imagination needs to go beyond manicured spaces. A tree park would not be comparable in terms of the many benefits of the existing Turahalli forest.

We should always ask ourselves if we are comfortable thrusting the remaining green lungs of the city, like Turahalli forest, into the concrete uncertainty of man-made spaces.

[With inputs from Seema Mundoli, faculty at Azim Premji University]

Also Read:

- Tree park beda okay, but what’s the vision for Turahalli?

- WATCH: Turahalli: Govt’s mission or civil society’s vision?

- Why a shrinking Bannerghatta forest should worry Bengalureans

- Bengaluru’s yes to Hesaraghatta film-city means a no to the Lesser Florican

- City of blinding lights: Artificial light disturbs nature’s processes in Bengaluru

Interesting and inspiring article. We need more young people who care about and for nature!

Good article

Great article! Brings up some very key points to think about.

can government do something about hyper concretisation of all private spaces? Apartments and offices can be asked to leave a percentage “open soil” to allow groundwater recharge. Please governments!! This city is becoming unliveable day by day. Read the article about concrete in Guardian sustainability.

We owe this to our children.

Insightful and articulate. Congratulations to all three writers.