This article is supported by SVP Cities of India Fellowship |

In the last few years, have you found yourself perspiring more than usual, while walking in core areas of Bengaluru city like Kalasipalaya? Well, it’s not just you. These are effects of the ‘urban heat island’ becoming more commonplace in the ‘Garden City’.

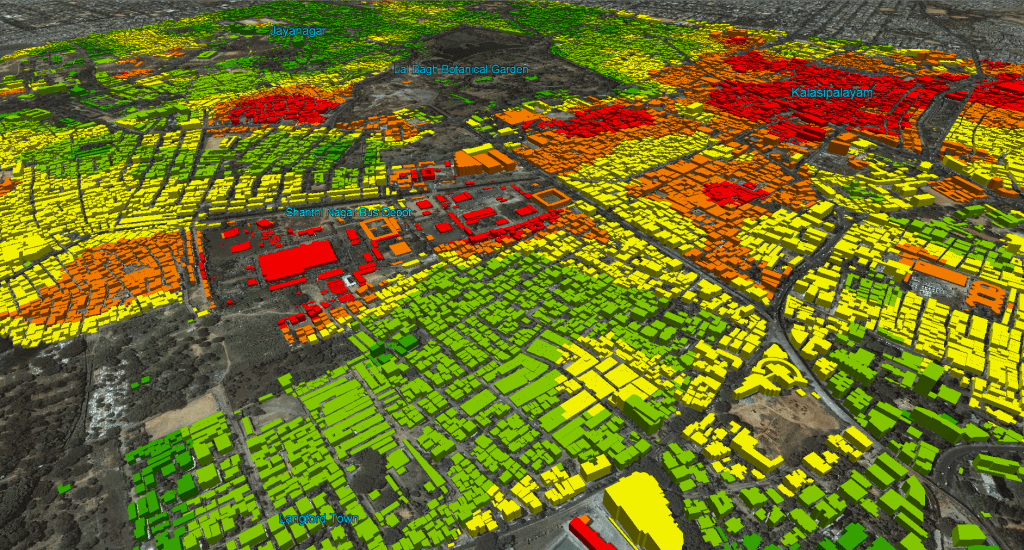

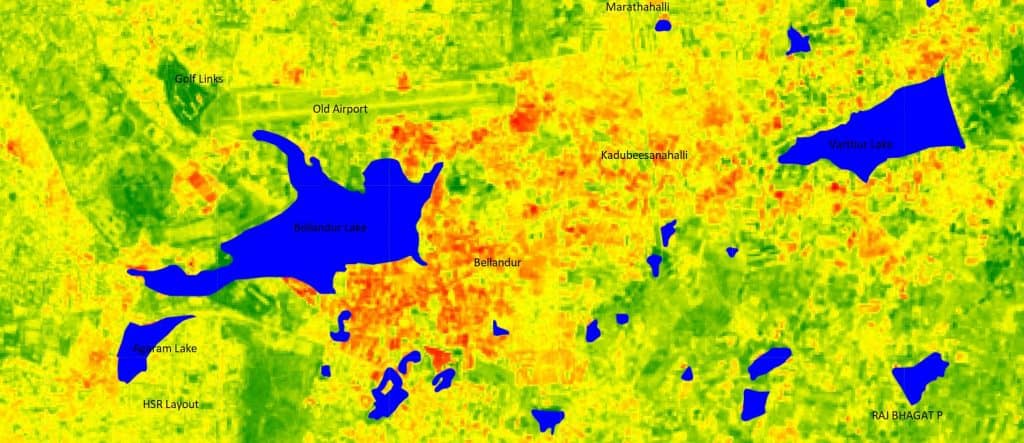

Temperature ranges in core Bengaluru. Graphic: Raj Bhagath Palaniswamy, World Resources Institute (WRI)

This graphic by Raj Bhagath Palanichamy, a researcher at the World Resources Institute (WRI), as part of the City Water Assessment Tool, shows temperature ranges in core Bengaluru. Neighbourhoods like Jayanagar (the green section in the top left of the image) and Basavangudi are facing less exposure to higher temperature when compared with Kalasipalaya (the red portion in the top right of the image) or Siddapura.

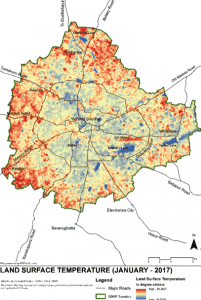

Land Surface Temperature measured using Satellite Images shows the actual temperatures in Bengaluru which varies from 38.2° C to 24.6° C. The temperature variation is caused due to micro climatic conditions, land cover, urban form among other causes. High temperatures are observed in the barren areas, land cleared for construction, airports, bus terminals, industrial areas, and other areas with large amount of concrete / tar surfaces whereas lower temperature are observed over water bodies and densely vegetated areas. Image: Raj Bhagath Palanichamy

This is because of the lack of tree cover and parks in the latter neighbourhoods. Areas such as Shanthinagar bus depots /workshops (the big building in the centre) are heat spots. People working/living in these places are exposed to higher temperatures. The heat island phenomenon also results in higher night time temperatures in densely built up areas like Commercial Street, like a TERI study showed.

It’s not just central Bengaluru. Raj Bhagat’s analysis showed that in all, 2.6 million Bengalureans were exposed to temperatures higher than average between January and March 2017.

Emissions from the stagnant vehicular traffic add to the pollutants and heat, in turn prompt people to switch on air conditioning. This releases more heat and pollutants.

“Karnataka’s emissions are around 4% of the national carbon dioxide emissions,” says the Karnataka Climate Change Action Plan Report submitted by Bangalore Climate Change Initiative – Karnataka (BCCI-K), May 2011. This would have gone up by now, as vehicles, buildings and people have only increased, and green spaces have reduced.

BCCI-K has projected Bengaluru Urban district will get hotter by around 2° C in the years 2021-2050, compared to the temperature seen between 1961-1990. Apart from the known effects of heat on the human body such as heat stroke and mental fatigue, prolonged exposure to heat can cause severe health diseases like cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases among others.

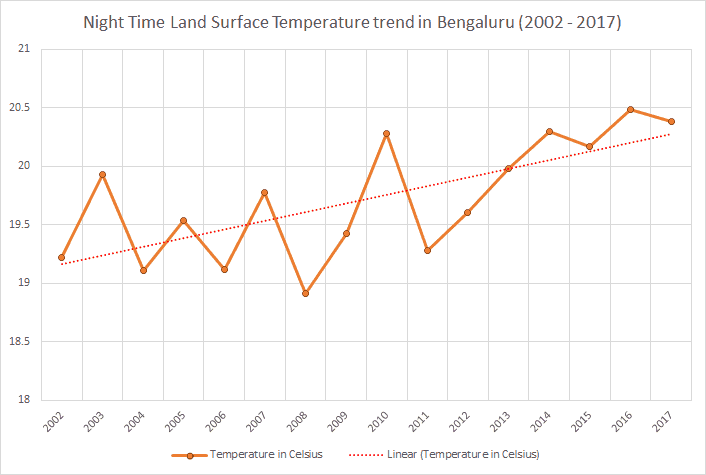

Trend in Land Surface Temperature. Data Source: MODIS (USGS / NASA). Chart: Raj Bhagat Palaniswamy

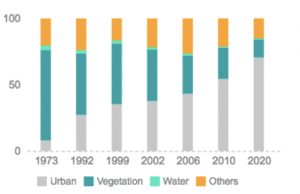

Dr TV Ramachandra of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) has studied Bengaluru’s urban space. His research clearly establishes the correlation between temperature and loss in vegetation. The study Insights to Urban Dynamics through Landscape Spatial Pattern Analysis shows that area under vegetation has declined from 72% (488 sq.km in 1973) to 21% (145 sq.km in 2010). The situation has been worsening in the more recent past – the study notes, vegetation has decreased by 32% from 1973 to 1992, by 38% from 1992 to 2002 and by 63% from 2002 to 2009.” Bengaluru saw a 584% growth in built-up area over the past four decades.

Image: Data from the study ‘Insights to Urban Dynamics through Landscape Spatial Pattern Analysis’ by Ramachandra T V, Bharath H Aithal and Durgappa D Sanna shows land Usage in Bangalore and how vegetation has drastically reduced. Graphic: Nikita Vashisth.

Increase in pollution

The study, Effect of street trees on microclimate and air pollution in a tropical city by ecologists Harini Nagendra, Lionel Sujay Vailshery and Madhumitha Jaganmohan shows the relationship of environmental differences with the presence or absence of tree cover. Suspended Particulate Matter (SPM) were high on roads without tree cover, with 50% of the roads showing levels approaching twice the permissible limits, while 80% of the street segments with trees had SPM within permissible limits. (60 micrograms per cubic meter).

The study states that, “street segments with trees had on an average lower temperature, humidity and pollution, with afternoon ambient air temperatures lower as much as by 5.6 degree C, road surface temperatures lower as much as by 27.5 degree C and sulphur-dioxide levels reduced by 65%.”

Increased flooding

It is obvious Bengaluru is increasingly flood prone, thanks to increasing built up area.

Urbanisation between 1973 to 2017 had a heavy impact on the decline in green spaces – there has been a 1028% increase in paved surface during 1973 to 2017, states a 2017 IISc study, Frequent Floods in Bangalore: Causes and Remedial Measures.

Vegetation decrease in the section between Bellandur and Varthur (1990 – 2018) Graphic: Raj Bhagath Palaniswamy

This visualisation shows vegetation decrease in the section between Bellandur and Varthur (1990 – 2018), denoted by red patches. The rampant urbanisation in the flood plains between the two lakes has been one of the causes for urban flooding faced in the Outer Ring Road over here.

Trees are critical for effective groundwater recharge, as they increase water retention, absorb water and slow down the rate of water run-off. They also reduce the intensity of rainfall and in turn flooding by stabilising the soil and channeling water safely.

@BngWeather @ChennaiRains An animation that I made for Bengaluru. Urbanization of flood plains (1990-2015) shown in red pic.twitter.com/8Bi4OxP7uy

— Raj Bhagat P #Mapper4Life (@rajbhagatt) November 2, 2017

What does Bengaluru really need?

More trees. More open green spaces. WHO standards recommend at least a minimum of 9 square metres green space per capita for better health and well being.

Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) says the city has around 50 lakh trees, even as it is yet start the long pending tree survey. However, a study by T V Ramachandra, Bharath H Aithal , Gouri Kulkarni and S Vinay on Green Spaces in Bengaluru: Quantification Through Geospatial Techniques estimates the numbers are closer to 14 lakhs – the city has just one tree for every seven persons. The study says, “Overall improvements in human well-being in urban areas necessitate at least 33% green space that ensures at least 1.15 trees/person.”

What is BBMP doing?

On the one hand, many trees are cut in the city for widening roads, or sometimes just to make way for hoardings or parking. Tree planting is tendered out to contractors who do not do a proper job of maintenance, because their bills are often not cleared. Saplings planted in many areas go unattended, and die in a few months, with no one to water or care for them. Another common mistake is to plant saplings on narrow roads where there is no parking space, automatically leading to removal of saplings or cutting of the trees by residents.

In the monsoon season of 2017, BBMP planned a drive to plant one lakh saplings by involving citizens who could request saplings for free, using an app. The app had 10,000 downloads but it is not clear how many saplings were actually planted by citizens.

BBMP’s website says they planted over 1,20,000 saplings. Vijay Nishanth, a green activist is sceptical about these claims, “If they have really planted this, it’s good; but how many had tree guards? were they watered properly? how many survive?”

Most drives are focused on streetside tree planting; however the real effect of soaring temperatures and flooding caused by vegetation loss can only be countered by large scale forestry programmes.

Ecologist Harini Nagendra points out the need for large connected patches of green space, “Large expanses of concrete cannot be cooled by just small stretches of avenue trees.” Connected stretches are also required to support biodiversity; Animals like slender loris and some birds need space to move around.

While there are reserve forests outside the city, near Nandi Hills and at Bannerghata park., the only green stretches in between are Lalbagh, Cubbon park, GKVK campus, army areas and some educational institutions. Harini says these are not protected and at risk of being encroached or built up.

In addition Harini notes that environmental and ecological benefits provided by a large mature tree cannot be substituted by planting a small number of saplings; The ability of trees in reducing temperature always depends on their size and girth.

Given this, what can we do to alleviate the problems caused by this extensive loss of vegetation in Bengaluru?

In the next part, we will look at initiatives which are working to fix to these issues.

~~~

Nikita Vashisth is a data journalist. Meera K is co-founder, Citizen Matters.

|

This article is supported by SVP Cities of India Fellowship. The Insights into Bengaluru series on ‘Greening Bengaluru’ includes: |