Ever wondered what happens to the onion peels or pieces of plastic that you throw casually in the dustbin? Every bit of waste that we generate has a long journey, that often goes unnoticed. It goes through a lot of procedures and undergoes various transitions. Understanding the journey of waste helps citizens contribute more to the cause of waste management.

Chennai generates 5600 tonnes of waste every day. Let’s take a look at the various measures being implemented by the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) on Solid Waste Management (SWM) to present the story of trash.

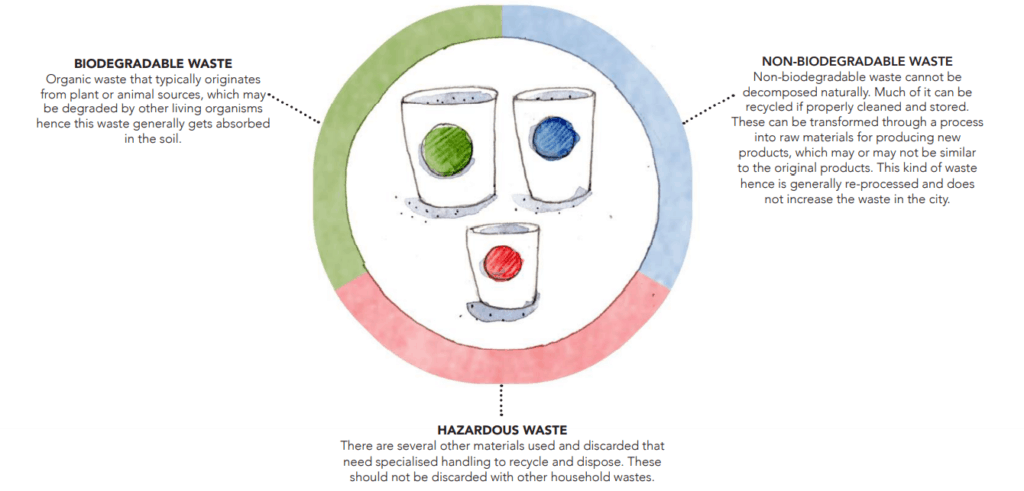

The SWM bye-law mandates source segregation of waste into four categories: biodegradable, non-biodegradable, domestic hazardous waste, and construction and demolition waste.

If you are a law-abiding citizen who puts the trash in separate bins (Biodegradable or wet waste in a green bin, non-biodegradable in blue and medical waste in red bin), the journey of the waste is less miserable. You are indirectly helping the conservancy workers, too, who otherwise have to segregate the soggy, foul-smelling waste at the Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs). The waste material is basically segregated into different streams of waste fraction (paper, plastic, packaging paper, bottles etc.).

The journey of waste varies for different localities of Chennai. In a few localities, sanitary workers collect the segregated waste from your doorstep. In other places, citizens dump the waste (mostly non-segregated) in the nearest dumpbin. A team of workers clear the dumpbin once in a day or two, depending on the quantity of waste.

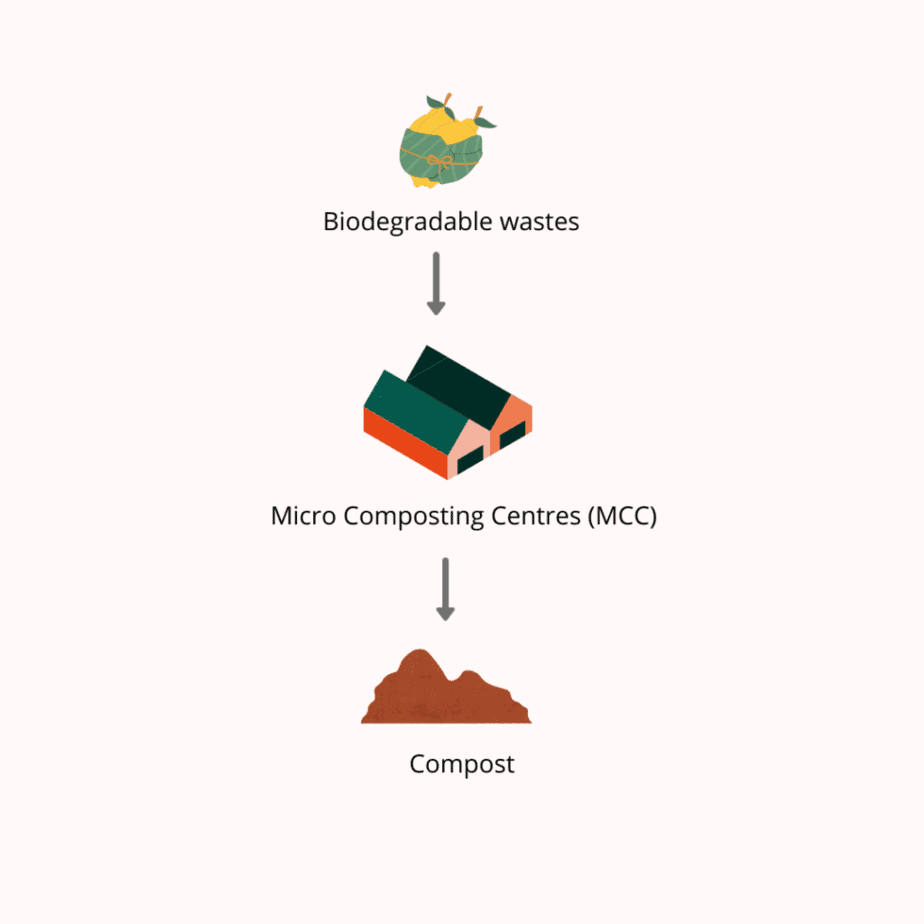

Waste to compost

Chennai follows a decentralised waste management system. The wet waste from households goes to the Micro Composting Centres (MCC) in their respective zones that process tonnes of wet waste every day. The data provided in the civic body’s website shows that the city has 141 MCCs.

Enter an MCC and what you’ll see include a waste receiving platform, shredder with conveyor belt, composting tubs, stabilisation area and sieving. The biodegradable waste offloaded at the MCCs is shredded to fine particles and composted.

Other component units include:

- Ordinary compost

- Well-ring

- Vermicompost

- Biogas plant

- Biomethanation plant

- Slaughter house

- Sintex

- Mulch pit

- Earth pit

- Windrow

- Well ring units (phase-II)

GCC has tied up with residents’ welfare associations, government agencies like Tamil Nadu Horticulture Department and organisations for selling the compost. So, the peels of cucumber or the leftover food waste becomes compost, which is used in organic farms or sold to residents for Rs 20 a kg.

From coconut shells to fuel?

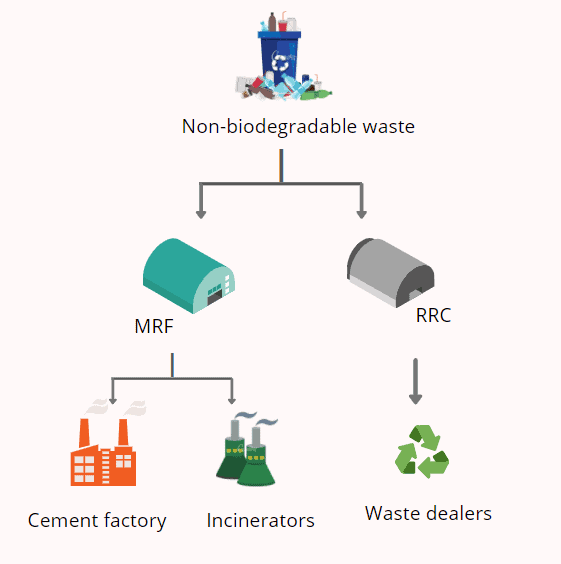

The non-biodegradable waste such as plastic covers, coconut shells, metals, iron rods, etc. are further separated, processed and stored for later use as raw materials for reusing/reprocessing at the MRFs.

Can dry waste be used for cement manufacturing? Certainly! Waste such as cotton boxes and multilayer plastic are stored at the MRFs and sent to Dalmia cement unit.

Besides that, 10 tonnes of dry waste are incinerated at the incinerator in Manali.

What happens to iron rods, thermocol, leather products, tyres, footwear, coconut shells, glasses and other low value items? Such waste is stored at Resource Recovery Centres (RRCs) from where the private waste management companies authorised by the civic body, take it for recycling/upcycling. For instance, Waste Winn Foundation collects thermocol and coconut shells.

“Thermocol is melted to make saree beads and buttons. Similarly, the coconut shells are used to produce alternative fuel,” says I Priyadharshini, CEO and Founder of WasteWinn Foundation.

Vendors approved by the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board (TNPCB) collect the domestic hazardous waste such as sanitary napkins, syringes and medicines from Zone 1 once in a few days. Domestic hazardous waste from other zones is taken to the dump yard as the construction of domestic hazardous waste collection centres is still underway.

The city generates around 500 tonnes of building and demolition waste every day. At present, the civic body disposes of the waste in the dump yard.

When the waste is not segregated

When mixed waste is handed over to the conservancy worker or dumped at the bins, it all lands in the dump yard. The lorries offload the wastes from the trash cans to the transfer station for assessing the weight. From there, the garbage will be disposed of in either of the two dump yards at Kodungaiyur and Perungudi.

What happens when there is no space in the dump yards?

Afroz Khan, urban governance researcher with Citizen consumer and civic Action Group (CAG) says it leads to dumping of waste either in open land in the outskirts of the city, or in water bodies like canals, rivers etc.

Another practice followed in our country is burning the waste in dumpyards or open spaces to make space for new waste. This comes with its own set of problems.

While it does seem like a convenient option to dispose of the waste in dump yards, the real problem is invisible and of great concern. “Biodegradable waste in the dumpyards emits anaerobic gases like methane and other harmful greenhouse gases over time. Non-biodegradable wastes like plastics leach chemicals into water and soil. A recent study has shown that commonly used plastics produce methane and ethylene under hot weather conditions like ours,” says Vamsi Sankar Kapilavai, senior researcher at CAG.

Although novel methods are being implemented for waste management at the city level, the real problem of waste has only one solution — reducing household waste generation. Whatever minimal waste is essentially generated must be segregated and managed by us — by disposing of organic waste in situ through home composting and upcycling the rest, whenever possible.

Very interesting but the final end results (specifics) of the end products are not given. What happens to unsegregated dumps seems problematic. Dumping in outlying open areas or in rivers and waterways does not seem realistic. Burning would be better than that!