Joseph and Mariyam lost their only daughter Nivi to a speeding car that hit her on OMR a couple of years ago.

“Road accidents due to speeding vehicles are prevalent in OMR and ECR. What we do not understand is why the government has not taken any measures to regulate speeding vehicles. How many more lives should we lose before we find a solution to the issue,” asks Joseph.

In a bid to address this problem, the Greater Chennai Traffic Police (GCTP) recently came up with a plan to enforce speed limits in Chennai.

Speed radar guns will be used to detect speeding violations and Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras that are capable of generating e-challans will also be installed.

However, the announcement received backlash from certain quarters in social media with arguments that this was yet another move by the GCTP to levy hefty fines on road users.

Later, the GCTP clarified that the speed radar guns and the speed ANPR will only be used for a preliminary study to draw up speed limits for Chennai roads.

While much of the criticism against the enforcement of speed limits was around the possibility that vehicle users could be fined arbitrarily, there is a much larger issue to address here.

According to the 2021 data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Chennai stands second among the metropolitan cities with the highest number of fatalities due to road accidents.

Can setting speed limits on urban roads be the solution to curb accidents and create a safer experience for road users in Chennai?

Read more: Speeding vehicles, traffic biggest barriers: Chennai cyclists

Link between speeding and accident fatalities in Chennai

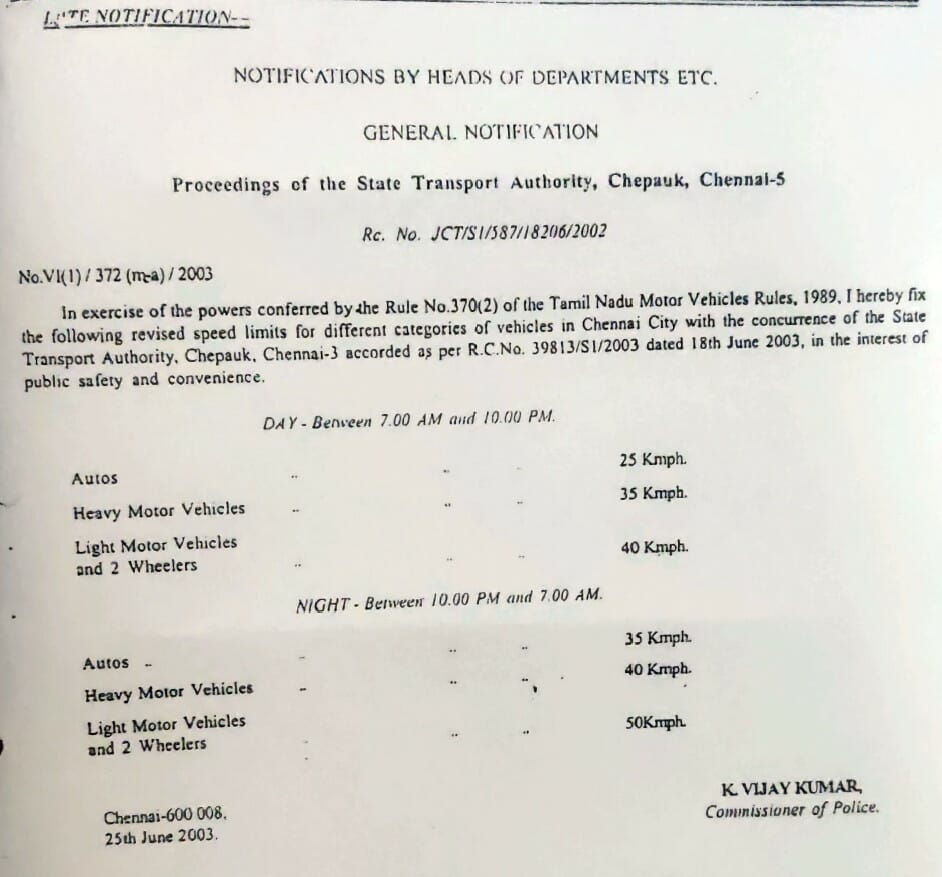

According to the 2003 notification accessed by the CAG through the Right To Information Act, the speed limits that were raised by the GCTP are as old as two decades.

Sumana Narayanan, Senior Researcher, CAG says that the speed limit was set 20 years ago and the GCTP is only enforcing the law now.

“These are very reasonable speed limits. If we look at the data from the government itself, the maximum number of road accident fatalities in the country and also in the city is due to speeding. The priority here is to ensure the safety of all the road users, especially the vulnerable ones,” she says.

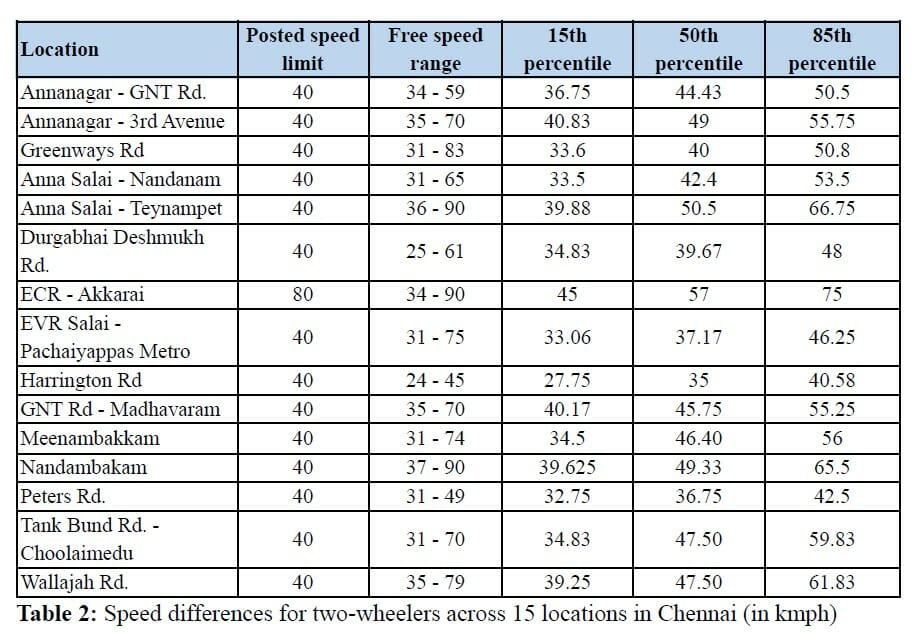

A study conducted by Citizen Consumer and Civic Action Group (CAG) in 2022 that analysed the speed of different vehicles on 15 arterial roads in Chennai also found that 85% of the two-wheelers travelling on the stretches crossed the permissible speed limit of 40 kmph.

“Even if we say we are brilliant drivers, we cannot control everything on the road. The UN and WHO have said that the urban speed limit should be 30 kmph. This is the safe speed limit for everybody. The risk gets high for vulnerable road users like pedestrians, cyclists and motorists when the vehicular speed increases. This is the group that has the maximum number of deaths,” she notes.

Adding further on the need to save vulnerable road users from fatal accidents, she says, “In many countries, there are separate lanes for pedestrians, cyclists, motorists, cars and other vehicles. Whereas in India and particularly in cities like Chennai, we can find motorists driving on the pedestrian lane. We have to rethink our attitude towards driving and also how we treat vulnerable road users.”

Santhosh Loganaathan, an Urban Development Professional who is currently Deputy Manager at Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), explains that across the world, there are multiple cities that collect road fatality data based on the impact of the collision vehicle.

“If we look at the research findings, any collision that happens beyond 40 kmph has a 70% mortality rate. This means any vehicle that goes beyond 40 kmph and hits a pedestrian, there is a 70% chance that the person might die,” he points out.

Hence, globally it is advised that the only way to reduce road crashes or road fatalities is to ensure that the impact speed is low. Thus in most cities, 30 kmph is the recommended speed limit in areas like schools or residential areas. The speed limit is set from 40 kmph to 50 kmph on arterial roads in some cities. However, a speed limit beyond 50 kmph is not advised at all.

“This is the logic behind connecting road safety and speed limit,” he adds.

Read more: Walking in Koyambedu, OMR or Chennai Central? Be cautious, warns study

Better urban planning for introducing speed limits in Chennai

Tackling speeding is a common-sense solution to the issue of Chennai’s problem with road accidents.

But a multi-pronged approach that is not just reliant on punitive measures such as fines is necessary to curb speeding on urban roads.

Road design should be altered in a way that forces the vehicles to slow down and is also safe for every road user. Such speed-calming measures can range from installing speed breakers or narrowing down certain sections so that there are little islands which are raised where only pedestrians can go.

“There are different design elements that urban planners use. A combination of sustainable and safe road designs along with enforcement and penalties,” Sumana adds.

“The other day I was driving along the Anna Library stretch in Kottupuram. When there is not much traffic, one will feel like going at 80 kmph. Automatically you will end up accelerating the vehicles on such roads. There is no single signboard on the speed limit in the entire stretch. Once the signboards are put up, then imposing fines will work,” says Sumana, adding that the only thing that the police should do now is put out proper signboards on the speed limits in every important area.

“Right now, I do not find such signboards in most parts of the city. This is very crucial,” says Sumana.

“In Chennai’s context, we see most speeding vehicles on arterial roads like OMR, ECR, and Anna Salai which are designed as highways,” says Santhosh.

“If it is a residential zone, we can install barricades or speed breakers which will slow down the vehicles by design. The average speed is quite low in residential areas though there are exceptions. However, on highway roads, especially during low-traffic times, it is difficult for vehicle users to slow down. Irrespective of what the posted speed limit is, the lanes are wide enough and are designed in a way for vehicles to speed through them. Even with enforcement, there is only a certain level of compliance that can be expected. The only solution is to design the roads for low speeds,” Santhosh notes.

Santhosh says that design interventions can be proposed to slow down the vehicles at the strategic locations.

“There are also design elements that can prevent collisions which can be considered for the selected junctions,” he adds.

Citing an example, he says OMR is considered an expressway by design.

“We can see a lot of pedestrian activity in OMR. An expressway can be called so only when there is an access restriction for pedestrians. If the access is restricted, the speed limit can even be 80 kmph and there will not be many accidents. But when we call a stretch an expressway where there are a lot of commercial and pedestrian activities, accidents are inevitable. As a long-term solution to this, speed radar guns can be used in these areas to analyse the behaviours of road users. The collected data should be used to look at the design elements that contribute to the accidents. In certain situations, the lack of street lights or bad roads can also be a contributing factor. Such design faults should be rectified,” he notes.

M Radhakrishnan of Thozhan, a non-governmental organisation that has been creating road safety-related awareness programmes, suggests framing localised plans to curb speeding.

“There are around ten market hubs in Chennai like the ones in Koyambedu, T Nagar, and KK Nagar. Similarly, there are many school zones as well. Traffic regulations should be made at such particular zones during peak hours rather than setting an arbitrary speed limit,” he says.

Read more: Why does Chennai see so many road accidents?

Ensuring average speed of vehicles in Chennai

“One backlash the government face while enforcing the speed limit in Chennai is that the commuters are already stuck in traffic. If we look at the average speed of the vehicles that travel from any point A to B, it will only be between 35 kmph to 40 kmph. It will be much lesser during the peak hours due to bottleneck traffic,” says Santhosh.

“As a solution to this, design the intersections and traffic signals in a way that there is a good amount of average speed. Ensuring the average speed of vehicles in a city like Chennai to 20 kmph is much better than putting random arbitrary speed limits that they cannot even enforce in future,” he adds.

Santhosh points out that one way to ensure average speed is by using the Intelligent Traffic Management System (ITMS).

“It works in such a way that all the traffic signals are networked through ITMS and if the commuters happen to wait in one traffic signal for a longer duration, then they will not have to wait in any other signal along the stretch. The traffic signals are open continuously for the vehicles to keep moving. Traffic congestion happens when vehicles have to stop at every signal. When that can be avoided using ITMS, the average speed can also be ensured and the roads will also be safe for all the road users,” he explains.

Sumana adds that the idea that if you drive only at the posted speed limit will take more time to reach the destination is not accurate.

Several research findings have shown that when you have vehicles operated at different speeds, it will eventually slow you down.

Explaining this further, she says, “Imagine you start driving at 60 kmph on a road. After a few meters, you will catch up with the cars and other vehicles in the middle of the traffic and eventually slow down. On the other hand, if you maintain the speed of 40 kmph and all other vehicles are also moving steadily at the same pace, it will take the same amount of time to reach the destination. This will also help in saving on fuel. The accelerating and decelerating are not fuel efficient.”

“The mentality of a commuter who drives through polluted and congested roads will be to accelerate the vehicle when the road is free. Given the situation, the traffic police should rather plan on traffic diversions to regulate the traffic at this point,” says Radhakrishnan.

Enforcing speed limits in Chennai

Now comes the key question of practical issues in the enforcement of speed limits in the city.

“For the given ratio of police to that of the city population, the police will not be able to identify every other offender,” says Sumana.

“There is a huge limitation on resources as well. This is where the technology comes to aid. Most of the metro cities are experimenting with technology to enforce the speed limits in their respective cities. In a recent incident, when I was in Delhi, the driver slowed down the car on an empty road. When I asked why he did so, he said that there was a camera and a signboard mentioning the speed limit to a certain number for some 200 metres,” she says.

Naveen B, a computer engineer, says, “I stop the vehicle at the stop line in the traffic signals these days even if I get late to the office as I have received e-challans twice for crossing the stop line.”

Radhakrishnan notes that compliance with using helmets and stop line discipline has been made a lot better with the use of cameras at the signals.

“Enforcement is only a small part of the issue. If all such design faults are addressed and yet the road users continue to violate the speed limits, that is where enforcement like imposing fines should come in. Otherwise, penalising every other road user for crossing the speed limit will not help the case,” says Sumana.

The use of technology is only one aspect of the solution to speeding on city roads.

Urban planners, city corporations and citizens all have a major role to play in ensuring road safety.

“So far, no city in India has cracked the code in enforcing the law on speed limit completely,” notes Sumana.

N.M. Mylvahanan, Joint Commissioner of Police (Traffic South), says, “The study commissioned by the GCTP is currently underway. The department was also collecting data from other metro cities to integrate the models here.”

Conversations around curbing speeding require looking beyond fines to adopt a holistic approach to understanding the behaviour of road users, faults in road designs, proper planning of civic works, coordination between various government departments and regulating traffic.