It had been raining in Chennai since the beginning of November 2021, which culminated in a heavy spell on November 7th, when the city recorded over 200 mm of rain.

The news of a cyclone hovering over the Andaman and Nicobar islands pushed the panic buttons of the otherwise pragmatic Chennai residents and the social media pages of weather bloggers were full of queries on flooding. The distress of the residents was justified, as Chennai is only 6.7 metres above sea level and more often than not, large areas of the city are quickly flooded after a shower. Memories of the misery of the Chennai floods in December 2015, resurfaced.

These incessant rains since the first week of November increased the water table in many areas. In low lying areas, to be precise (areas which were once waterbodies or floodplains), groundwater has been seeping into basements and the ground floor of houses.

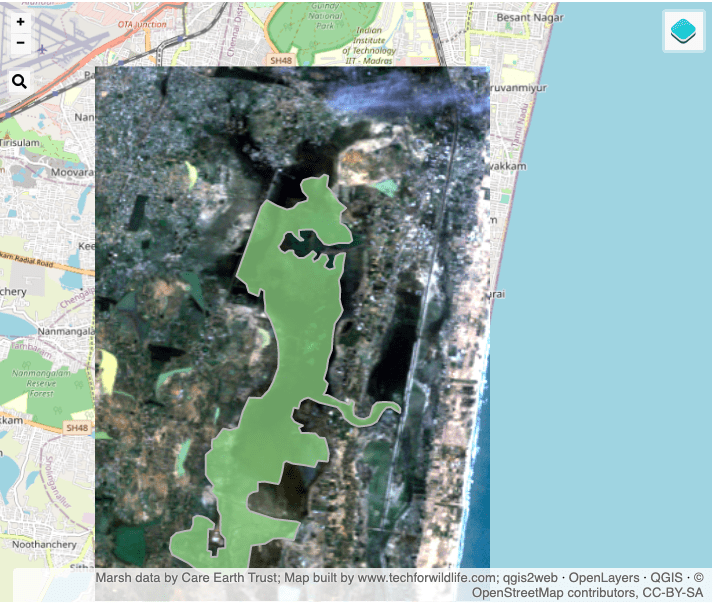

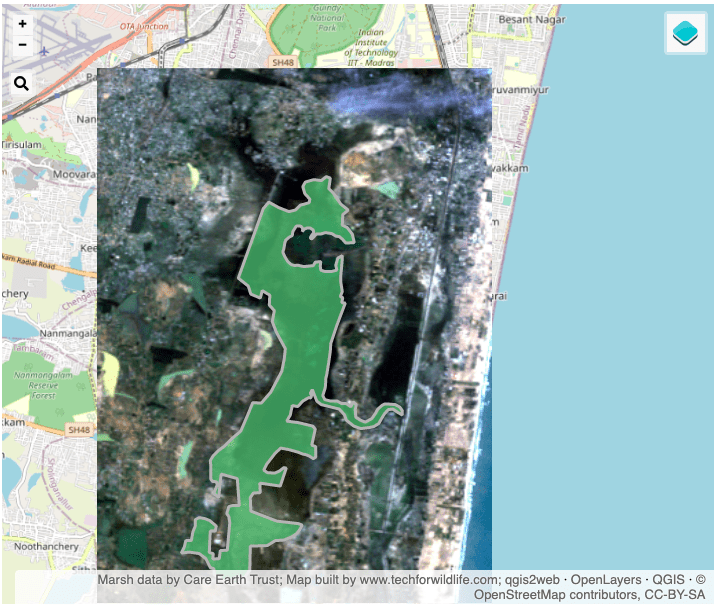

As Chennai went through another major flooding, the importance of the Pallikaranai marsh came to the fore once again. The marsh, the last remaining natural freshwater wetland in Chennai, acts as a sponge, storing the heavy monsoon rains and releasing them during dry months. There have been recent efforts to protect what’s remaining of the marsh and raise awareness levels among the public.

The shrunken natural sponge

The Pallikaranai marsh, known as kazhuveli (waterlogged area) in Tamil, is a wetland and falls within the Perungudi and Pallikaranai villages of the Kancheepuram district and lies parallel to the Buckingham Canal in Chennai. The Old Mahabalipuram Road (OMR), also known as the IT Corridor or Rajiv Gandhi Salai was inaugurated in 2008, and cuts across the marsh as does Chennai’s Mass Rapid Transport System (MRTS) railway line and stations. The presence of a large number of Indian and multinational companies on the OMR has led to the development of residential and commercial spaces in the areas adjacent to the OMR.

Jayshree Vencatesan of Care Earth Trust told Mongabay-India that the importance of the Pallikaranai wetland has been forcibly brought to the notice of the residents of Chennai during the two major floods (in 2015 and now in 2021) which inundated this seaside metro.

Read more: Why do we see fewer migratory birds in Pallikaranai?

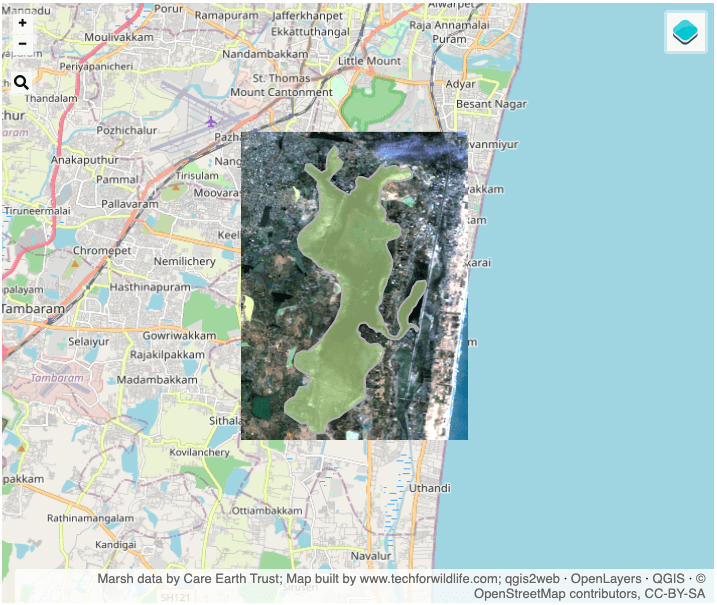

According to research done by the Care Earth Trust in 1991, the marsh covered 2450 ha in 1991 but by 2015 the marsh had lost out to the various developments including the railway line and covered just 600 ha.

Despite its reduced area, the marsh acts as a sponge that stores the heavy monsoon rains and releases them during the dry months, said Vencatesan.

Vencatesan said that in 2007 Chennai suffered very heavy rains which flooded parts of the city. The then Chief Minister J. Jayalalithaa did an aerial survey of the marsh and immediately understood the benefits of protecting and preserving the wetland. The floods also revealed that the dumping of toxic waste along with the discharge of untreated sewage had caused major damage to the flora and fauna in the marsh.

The first step towards changing the land use of the marsh was taken on April 9, 2007, when the government of Tamil Nadu notified a major portion of the Pallikaranai marsh as a reserve forest area and brought it under the Tambaram range of the forest department and named the Pallikaranai Swamp Forest Block. The initial survey by the government demarcated 317 ha of the marshland as a reserve forest. Earlier, this land was classified under the revenue records. With this demarcation, stringent action could be taken against encroachers and polluters under the Tamil Nadu Forest Act and Wildlife Protection Act.

The Pallikaranai marsh has been a sink for the city’s sewage and also has two garbage dump yards. On March 25, 2008, the High Court of Madras said, “It would be wise and economically sensible to use the marshland as a natural flood-control option rather than tamper with natural drainage, and then re-invest in flood control or damage mitigation at a later stage.”

However, despite the pleas of the civic groups and environmentalists the encroachments and dumping in the marshlands continued. In 2015, when major floods hit the city, the toxicity and pollutants in Chennai’s wetland came as an ugly wake up call for the city’s residents and the administration.

Steps towards Ramsar Convention recognition

Supriya Sahu, Principal Secretary, Forests and Environment, Tamil Nadu Government told Mongabay-India that the aim of the administration is sustainable development and that the government is fully committed to protecting what is left of the marsh.

Recently, the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin inaugurated a walkway and viewing gallery at the Pallikaranai marsh which environmentalists say is a step in the right direction as it will raise awareness levels among the public.

Sahu said that the government was working towards the Pallikaranai marsh being declared as a Ramsar site following a Madras High Court directive. The government has also taken steps to declare the marsh as a bird sanctuary, as a large number of migratory birds visit the area.

Justice N. Kirubhakaran of the Madras High Court, had ordered, on September 24, 2021, the Tamil Nadu Forest and Environment Department prevent non-forestry activities in the marshland. The Court also passed an order to move the two dump yards located in the marsh to other parts of the city, and directed the government to reclaim unutilised land allotted to government industries and institutions. The forest department has begun this process, according to Sahu. The government has also started fencing the marsh on all sides and removing blocks in the water channels. According to the High Court order, a compliance report has to be submitted by December 21, 2021.

Read more: How an international tag can help save the Pallikaranai marshland

Vencatesan who has been studying Chennai wetlands since 2001, said that there was a change in the government’s stance after the 2007 floods and the marsh was declared a priority wetland. The Government has been cancelling various allotments for real estate and industrial developments since that time and reclaiming land for the wetland. Today the acreage stands at 700 ha.

Rectangular storm water drains: were they effective?

Among the recommendations implemented after the 2015 floods was a new storm water drain (SWD) project, which too fell short in protecting the city against the floods caused by heavy torrential rains on November 7 and 11, 2021.

Under the project – which was developed after the 2015 floods when Chennai Corporation engineers found that the drain network in many areas was either defunct or missing – the new SWD was rectangular in shape. This Integrated Storm Water Drain (SWD), as a part of the Smart City Mission, linked the SWD network to three river basins and an estuary (Adyar and Cooum basins, the Kosasthalaiyair and Kovalam basins).

Jayaram Venkatesan, Convener of Arappor Iyakkam, a people’s movement working towards transparency and accountability in governance, told Mongabay–India that Arappor had earlier filed Right to Information (RTI) petitions to ask for project reports on road names where SWD were constructed. They have not received any reply. There is also no map showing the storm water drain network in the city, he said.

Talking about the recent rains, Venkatesan said that in some parts of the city, the stormwater drains worked because they were about 400 to 500m from a water body or canal and also, there was a gradient that facilitated the water flow. In other places, the rectangular drains did not work because either they were not connected to water bodies, or they were filled with sediment and garbage including plastic.

According to Venkatesan, after the deluge, the Corporation crew were seen pumping the stagnant water into the sewage drains.

According to a news report published last month, Gagandeep Singh Bedi, the Greater Chennai Corporation Commissioner, said that he has insisted that changes be made in the SWD design after vetting by Corporation engineers. Bedi said that the recent flooding is not because of the SWD but because the system itself is getting strained.

[This story was first published on Mongabay. It has been republished with permission. The original article can be found here]