Yuvan Aves is a nature-educator, naturalist, writer and activist based in Chennai. He is the Founder-Trustee of Palluyir Trust for Nature education and Research, and along with his team of young naturalists, conducts a number of immersive learning experiences for children and young adults. These include walks and workshops in various geographies and biodiversity areas in Chennai. This type of teaching and learning has been termed as ‘nature based learning (NBL)’, which Yuvan explains, is a self guided, real world learning experience.

Yuvan’s team makes a range of NBL material and curricula for Chennai schools to apply. In an interview with Citizen Matters, he explains these terms using examples of various workshops he has been part of over time. He also sheds light on the equalizing potential of nature based learning, the nature of traditional environmental education (EVE), as well as the potential of NBL to stimulate action and involvement among people.

What is nature-based learning and how did you come to know about it?

Nature based learning can be understood as ‘letting the landscape be the teacher’. When you walk through a marshland for example, you learn about it by looking at the birds and insects , the water catchment, you get to speak to the people living there, their issues of resettlement and so on. It is real world engagement, where the student is not a passive recipient of knowledge, but an engager.

My first experience of conducting such a learning experience was during my late teens. I was living in a school campus in Chengalpet bordered by 3 villages, and was to conduct workshops for younger children from these villages. I decided to take them around their own local ecosystem in an attempt to encourage learning from creatures and direct observation of scenes in their everyday lives. We would visit paddy fields, we looked at ways of documenting local knowledge around plant diversity, document local fauna and their lifecycles,we set up a butterfly garden, among several other activities. The children’s interest in the ‘environment’ was much more heightened, as compared to the classroom set up. In fact, their academic performance also greatly improved.

I noticed that the local context acted as an extremely useful portal for children’s intrinsic motivation to learn, as opposed to when nature, among other subjects, is spoken of in abstract and ‘external’ terms, to the student. Ultimately, an understanding that we are part of the larger ecology and its continuums is an important vision in nature based learning pedagogy.

In Chennai, we conduct walks and immersive workshops in the Kotturpuram Urban Forest, Pallikaranai Marshland, North Chennai, Elliot’s and Kottivakkam Beaches, the banks of various rivers and more.

Read more: Chennai is home to nearly 150 species of butterflies. What do naturalists infer from that?

How can we understand this idea of a continuum in the context of Chennai?

A few days ago, we did a walk along the shores of Elliot’s Beach, starting from the Karl Schmitt Memorial, moving along the coast line. The walk aims to understand that particular coastal ecosystem. The creatures as well as the people living along the coast, their practices and culture would be a part of the coastal ecology.

During the workshop, we spoke about the artisanal fisherfolk’s view of the ocean, the local habitats mapped by them, the tides, fishing practices taking place that day, local languages to refer to biodiversity, wind patterns, etc. We often speak of the ocean as one blue thing, but it is so diverse as we move from place to place. How this changes life and people’s practices is an extremely important aspect of understanding the relationship with our environment.

The human is thus not outside of the ecological. So when I say nature-based education, human society, its politics and all its beauty and squalor are included, in a very non-isolated manner.

What are the key aims you have in mind when conducting nature-based learning experiences?

Over the years, I have developed two general goals for nature based learning:

The first is the process i.e. engagement with the real world, conversations and meeting realities. The second is the values that inform the pedagogy: which is prioritizing the well being of human and ecological systems. This sense of purpose is often lacking in the traditional schooling system – where syllabus and the market economy take center stage, putting both human and ecological well-being aside

In a traditional classroom, a child practices passive sitting, where they sit, learn to be obedient and recipient, they learn to follow given instructions, and to submit to authority. They practice this for fifteen or more years of their life.When they witness the hardships of others, ecological destruction, social evils, etc, why would they ask questions? They have been trained by the system to be passive and not question or create change. Nature based education children to develop a sense of active engagement.

There are many studies showing that children studying environmental science and who were exposed to real issues, field trips and engagement with landscapes, tended to take charge and grow in accountability for spaces far beyond themselves, as opposed to those who were only exposed to intellectual experiences – who developed little stewardship for their surroundings.

Self directed learning is also a key philosophy when it comes to nature based learning. This would mean that the child is empowered to take their learning forward at their own pace, style and leaning on their own lived realities. A certain topic can be understood in numerous ways, with various cross linkages, and entry points. A self directed learning scenario allows for this to happen, more so than a typical classroom, where the teacher is directing the entry points into a topic, or the focus of study. Self-directed learning could take many forms – beginning from giving a species field guide to groups of children, using activity sheets, making lesson plans with the learners, frequent feedback, having conversations with different people, preparing their own task plans, etc.

So typically, in any kind of experience creation, I want to allow for a mix of the two: self-directed learning as well as me directing some kind of experience. This direction could be in the form of facilitating a conversation with somebody there, pointing things out and speaking about it, sharing stories, and giving them a field guide.

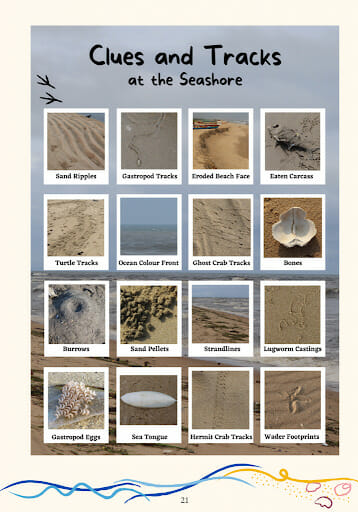

For the Elliot’s Beach walk, we made use of a coastal field guide to help with self-guided learning. The guide has pictures of around 160 species along Chennai’s coast for each child to hold, and observe. We had children drawing things they saw, learning new names of species, as well as the local names given to these species by communities living on the beach.

You mention the term ‘indigenous knowledge, which is an important part of understanding the ecosystems you want to learn from. What does it mean exactly?

Indigenous knowledge is a bit of a strange word. I’d rather describe it in a way of ‘Inhabitant’ and ‘exhabitant’ knowledge. If you look at a lot of artisanal fisher folk in places like Chennai, the beach and coast is part of their identity and selfhood. There is also a divinity and culture that they have formed around, the ocean and coast, as it is an important source of livelihood for them, and is part of their everyday life. Dwelling there comes with practices, knowledge and experience with that environment. This could be called inhabitant knowledge as they are part of that ecosystem.

Exhabitant knowledge would be like a commercial fishing harbour. For the trawler, the ocean is not a part of their identity; you go to the ocean to exploit and extract. There are certain knowledge and practices emerging from this. This would be exhabitant knowledge. I like to keep these terms in mind when describing the relationship between humans and their ecologies.

Read more: How industrialisation has rung the death knell for Ennore’s ecology

Could you recount any workshops/nature walks you have conducted, which illustrate how the social and ecological are connected?

For Madras week we did a heritage tour for 24 people. We showed the change in landscape from South Chennai to North Chennai. North Chennai was initially called ‘Black Town’ – a discriminatory term – by the British as a way to refer to scheduled castes and daily wage workers who comprised the majority of the area.

If you look at North Chennai, it is a watery landscape. It is where the Kosasthalaiyar comes in, and in Manali, it darts north and spreads into 10,000 acres of wetlands. There are about 35 re- category (hazardous and deadly) industries here. As per laws regarding the setting up of industrial sites, watery landscapes are actually avoided as the effluents will travel far, and the land is shifting.

However, numerous factories have been built here over time, as the people here do not have the financial and political power to stake a claim on the lands they live in. The same factories cannot be set up in Besant Nagar; if Adani comes and sets up his factory here, his shares will plummet, as privileged people live here.

As soon as you cross Napier Bridge, i.e. the Cooum Estuary, towards Kasimedu Harbor, the beach vanishes due to coastal erosion from the port building.

We looked at the thermal power station industries, and the pollutants they release into the water. What happens is many do not have a cooling tower for the hot water they release. It kills local ecosystems, and you even hear stories of people dying because of the hot water. We use maps to observe the change in landscapes, greenery and natural systems.

This walk was done in collaboration with the Chennai Climate Action Group. We took people from South Chennai who are from privileged backgrounds, who can exercise their voice and have significant reach. Maybe later they will become volunteers in some sense. These walks are usually done with this intent.

What are some important observations you have developed while teaching and facilitating, over the years?

Nature based learning can be a great equalizing pedagogy for children from disadvantaged social and economic backgrounds. A team of us have been running an apprenticeship programme for children of the fisher-community at Urur and Olcott kuppam – two coastal hamlets at Besant Nagar, Chennai. Children from different social backgrounds and cultures show differences in how they grow and what capacities mature fast and slow.

We wanted to make their home-coasts (Elliot’s beach and Adyar Estuary), into a learning space, beyond any classroom. Fisher communities are historically marginalized in urban society. Difficult socio-economic conditions deeply impact the healthy growth of children through their developmental planes.

Not everyone is at the same level playing field in the traditional school setting, due to lack of resources, time, and access to different methods of learning. In these months, we’ve been seeing how studying their home coast really heightens their interest levels, even their overall language and understanding skills, but more than anything their intrinsic drive to learn through their native beach.

Another important observation is that nature based learning caters to various developmental stages as one grows up. Sensorial learning is extremely limited in traditional education. It is all mostly intellectual. Nature based learning is able to weave into this and take care of various children’s developmental needs.

Special note: We deeply regret that an unedited version of this interview had been unwittingly published earlier, which did not capture all the points that the interviewee had made. These have since been incorporated in the text.