Are you a Chennaite who has been to Marina beach since your childhood? Does the sight of the sea hold many happy memories for you? But how many of us know that Marina beach also has a fraught past, which counts as part of its history a police gun firing against fisherfolk who protested against beach beautification?

For many youngsters of this generation, the Jallikattu protests were the first time they saw a very different image of the beach – one as a site of protest. But that’s not the only point of contention that has seen protests.

Over the years, Marina beach has seen a lot of changes. Clean-up drives and beautification projects make headlines every now and then. Such efforts have been the pet project of successive governments, be it DMK or AIADMK.

The latest in a long line of projects which have been announced in this regard is the Rs 100-crore Chennai Shoreline Re-nourishment and Revitalisation Project, covering the 30-km stretch between the Marina and Kovalam.

Every time a project like this makes headlines, fisherfolk from various fishing hamlets along the shoreline are forced to mount a fight against it to protect their lives and livelihood.

Read more: Plan for smart pushcarts on Marina leaves hundreds staring at uncertain future

History of beach beautification projects

The fisherfolk’s fight for livelihood against the projects that are brought forth in the disguise of development and beautification is not new. It dates back to the 1980s.

As part of the beach beautification project in Marina, the fisherfolk who were engaged in this occupation for centuries on the stretch between Anna Square and the Light House in Marina Beach were asked to park the catamarans, boats and place other fishing materials like nets near the mouth of Adyar River and Cooum.

The fishing communities in the area were against the project as it was practically impossible to move the catamarans and boats from Adyar and Cooum every day to head to the sea.

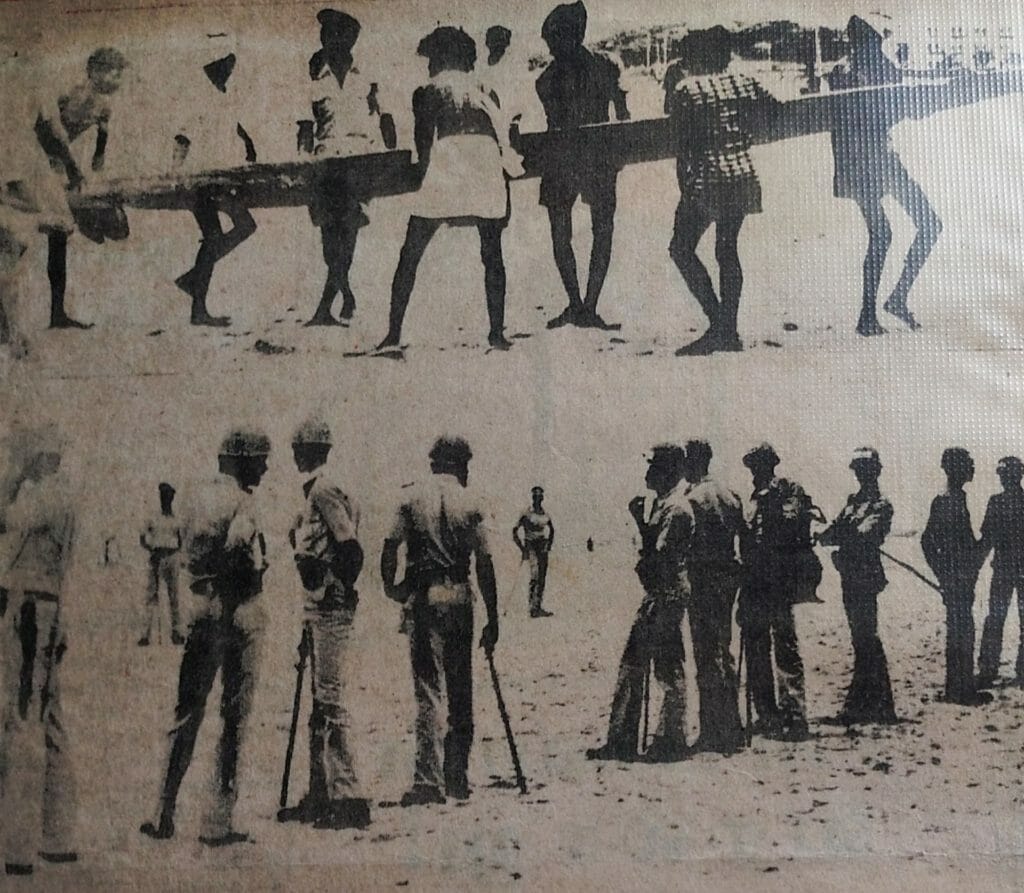

The then government led by late Chief Minister MG Ramachandran (MGR) deployed the police force and removed the catamarans, fishing nets and boats of the fisherfolks that were placed along the seashore of Marina without any prior notice on November 4, 1985.

This irked the fisherfolk. Hundreds of them gathered and went on a month-long protest from November 4th to December 4th. On November 7 1985, a fisherman, Godhandapani, set himself ablaze in front of the Secretariat to register his protest against the government’s insensitive move. Notwithstanding treatment, he passed away on November 9, 1985.

Meanwhile, the affected fishermen sought legal recourse in Supreme Court (SC). The State contended that the fishermen were free to carry out their vocation in any part of the sea during the day or night.

The state contented that the residences of the fisherfolk were not shifted but only the places for parking their catamarans and nets were changed to the specified place in the interest of public safety and public order.

The month-long protest came to an end with the police opening fire on December 4 which killed seven people including one youngster. The firing also injured several others. The SC then ordered the government to return the catamarans and other seized materials.

“It took more than seven lives to stop the project that tried to evict us from our lands in the name of beautification,” says K Bharathi, President of South Indian Fishermen’s Welfare Association.

Did their struggles end there? No. In January 2002, the then AIADMK government led by late Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the Malaysian government to make an ‘administrative city’ in Chennai. This included the ‘Marina Foreshore Development Scheme’ which involved building accommodation for multinationals and embassies and relocating the local fisherfolk elsewhere. This again became a stormy affair and protests were staged across the city.

“Notable activists like Medha Patkar took part and led our protests as well,” Bharathi says, adding that the continuous protests by the fishing communities forced the government to roll back the scheme.

Again in 2009, when the DMK was in power, an elevated expressway from Light House to ECR through Pattinampakkam, Besant Nagar, Thiruvanmaiyur and Palavakkam was proposed All these areas have many fishing hamlets. The officials conducted the survey and enumerated only those having patta. All others were termed encroachers and left in limbo. The fishing communities had to take to the streets in protest. “In 2011 when Jayalalithaa came to power she rolled back the project,” says Bharathi.

Between 2013 and 2015, protests erupted again on peak against the creation of the Loop Road from Light House to Srinivasapuram as it was in violation of Coastal Regulation Zone norms.

“Many people from the fishing community did not understand the adverse effects of the road initially. The government convinced them saying that a nice road would help them transport their product easily. However, now the government says that we are making the place filthy and are planning to house all the fishers in one place. They are building a market for us without any consultation with us. This will have serious implications on our livelihood,” says Bharathi.

Impact of moves towards beautification on livelihood

At present the fisherfolk of Nochikuppam are opposed to the move to create a single large fish market by moving all the sellers along Loop Road to one location.

Raghu, a 33-year-old fisherman in Nochikuppam, leaves for the sea as early as 3 am. He returns to the shore around 7.30 am.

Drying the net on the sea shore along with his peers while the women in their families are out there selling the fish, he says, “We need different kinds of fishing nets to catch different fish. Each net would weigh from 40 to 100 kilograms. They require two to four people to carry them. For instance, a fishing net that spreads across 400 square feet in the sea would weigh around 100 kgs and cost around Rs 1.5 lakhs. In case the net gets damaged, it has to be repaired which is again costly. If we are to be displaced, we cannot carry these nets everyday to the sea from elsewhere.”

There are fishermen like Raghu who fish between 3 am and 8 am in the mornings and again between 3 pm and 12 am. They own their boats and fishing nets.

On the other hand, there are fishermen who own ‘Peruvalai’ (large nets). They team up with a group of fishermen and fish on a large scale. They then share the produce and the earnings from the sale.

“If there are four fishermen who own a peruvalai in a hamlet, not all of them can go into the sea at the same time. Since there have been clashes between such groups earlier, every fishing hamlet came up with a system of its own that regulates and allows only one group owning peruvalai to go fishing in a given time,” says Bharathi.

Similarly, fishermen in each hamlet would know the nuances of where to get what fish in their part of the sea. “When all our residences and markets are all moved and clubbed together, all the fishermen would be forced to go fishing in the same territory of the sea and this would lead to clashes between different hamlets”, says Bharathi.

“There are days when fishermen from different hamlets would go fishing into the territory of other hamlets when they find fish that are sold at high cost could be found there. This even led them to fights breaking out right in the ocean. The government has no understanding of such territorial and livelihood issues and terms it a law and order issue. To resolve this, we came up with our own territories,” says another fisherman Kathiravan*.

Read more: Coastal zone management plan does not follow rulebook; communities feel betrayed

Women voice their concerns

Yamuna*, a fisherwoman in Nochikuppam, has two daughters. She, along with over 300 women from the locality, take an auto as early as 2 am and go to Kasimedu to buy fish. The auto would cost around Rs 100 each.

“We return by around 8 am and set up the makeshift shops on either side of the Loop Road. The customers come from 8 am till 11 pm at night,” she says.

Kavitha*, a fisherwoman who makes ends meet by cleaning fish, is staunchly opposed to the idea of moving to the fish market that is soon to be built near Nochi Nagar.

“Firstly, we were not consulted before making the project proposal. Secondly, the proposed site has a school nearby. We have set up shops in front of our homes and we have been doing the business here for centuries and so we would not move,” she says.

“If the government wants more space for roads they should be evicting the big bungalows on Kamarajar Salai and setting up shelters with water outlets for us. How will clearing us out of the picture make the beach look beautiful?”, many in the community ask.

Kiruthiga, a customer who was buying fish in Nochikuppam on a Sunday, notes that she prefers buying fish from the fisherfolk here as the fish is usually fresh. “I prefer buying fresh fish. I see the fishermen taking out fish from the nets here, whereas in markets, we get it from ice boxes”, she says.

Beauty in the eyes of the beholder

The officials from Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) say that the focus of projects such as the fish market is to make the beaches qualify for Blue Flag certification.

“It has a number of parameters, including safety, accessibility, water quality, beautification and environmental management. The preliminary work is are underway and the project details will be out in public once everything is finalised and the locals will be included in the process,” say the CMDA officials.

However, environmental activist Nityanand Jayaram says that beauty is subjective. “We do not know the exact plan of government. Based on the track record, we can see a high level of insensitivity towards the livelihood of the fisherfolk.”

There is a huge mismatch between the way the fisherfolk see the sea and the government sees the sea. “If the fisherfolk are refusing to move to ‘good’ shops given by the government, shouldn’t the government see that their idea of ‘good’ is not the fisherfolk’s idea of ‘good’?” he asks.

“If we look at economic productivity, the Nochikuppam market has been highly productive with zero investment from the government. Lakhs of rupees are in daily transactions and the money is going directly to the people at the bottom of the pyramid. Right from catching fish to selling it, the money stays within the locality. This would be disrupted in the name of beautification,” he says.

He adds that attempts to evict the fisherfolk have been ongoing for decades since the coastal real estate has become valuable. “What looks beautiful for my eyes should first be meaningful for the locals and I think there is a way for both to happen if the government takes a bottom-up approach,” he notes.

The fisherfolk in the locality see the current project only as a process of invisibilising them.

What remains to be seen is if the government would lend its ears to their plight or if history will repeat itself.

*names changed on request.

The Marina beach should be made convenient more for the poor, those who come by bus,train & 2 wheelers. Parking of cars in the service road should be banned. The rich can afford to go to the many resorts upto Mamallapuram and beyond.

Protection of the fishermen’s livelihood must be the Govt’s priority.