Krishna Ramesh, a farmer from Kachamaranahalli village, 21 km from the centre of Bengaluru, has lived under the shadow of a land acquisition notice since 2007. His five acres, the only land he owns, are among 2,558 acres notified for the Peripheral Ring Road (PRR) project, now rebranded as the Bengaluru Business Corridor.

The land sustains his family, yielding over ₹1 lakh a month. If the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA), the project’s planning authority, proceeds with the acquisition, Krishna, who is also the General Secretary of PRR Raitha and Niveshannadharara Sangha, will be left landless—his livelihood dismantled, his future uprooted.

Some news reports suggest that the BDA is offering record compensation to land owners. But, farmers and landowners like Krishna feel the compensation is too low, illegal, and unfair, and are not ready to give up their fertile lands.

For thousands of farmers, the PRR has meant years of uncertainty, blocked opportunities, and mounting losses. As questions remain about whether the project will truly ease Bengaluru’s traffic, its flawed execution has already left those caught in the middle of the acquisition struggling to protect their livelihoods.

Risk of displacement

“If the acquisition happens, we will have to move at least 50 km away from our village,” says Krishna. Nearly two decades since the project was announced, the region has undergone rapid urbanisation. “In 2008, the BDA offered ₹11 lakh as compensation,” he recalls. “Back then, we could have bought land within two kilometres.” But today, high land value makes it difficult.

The anxiety is shared across villages. Gopal Reddy, a farmer from Sulikunte, says the compensation on offer is so low that it would not allow him to buy affordable, fertile land even within a 100-km radius. More than half of his four-acre land is notified. Gopal harvests flowers such as roses, gerbera and more. For him, this project means moving away from the major flower markets in the city, a critical setback to his livelihood.

While the BDA argues that the project is in the public interest, farmers question how it benefits them if it forces them to migrate out of the city, or even out of the state. “Are we not part of the public?” asks Gopal.

V Ravichandar, an urbanist and former member of the Bangalore Agenda Task Force, says that projects like these should benefit all stakeholders. “One thing is clear: for a project like the PRR to secure broad cooperation and succeed, it must be structured as a win–win proposition for all stakeholders,” he adds. “Any one party gaining at the expense of the other is not a sustainable solution.”

Also read: Ringfencing Bengaluru: STRR gains momentum while PRR struggles to get takers

Two decades of struggle

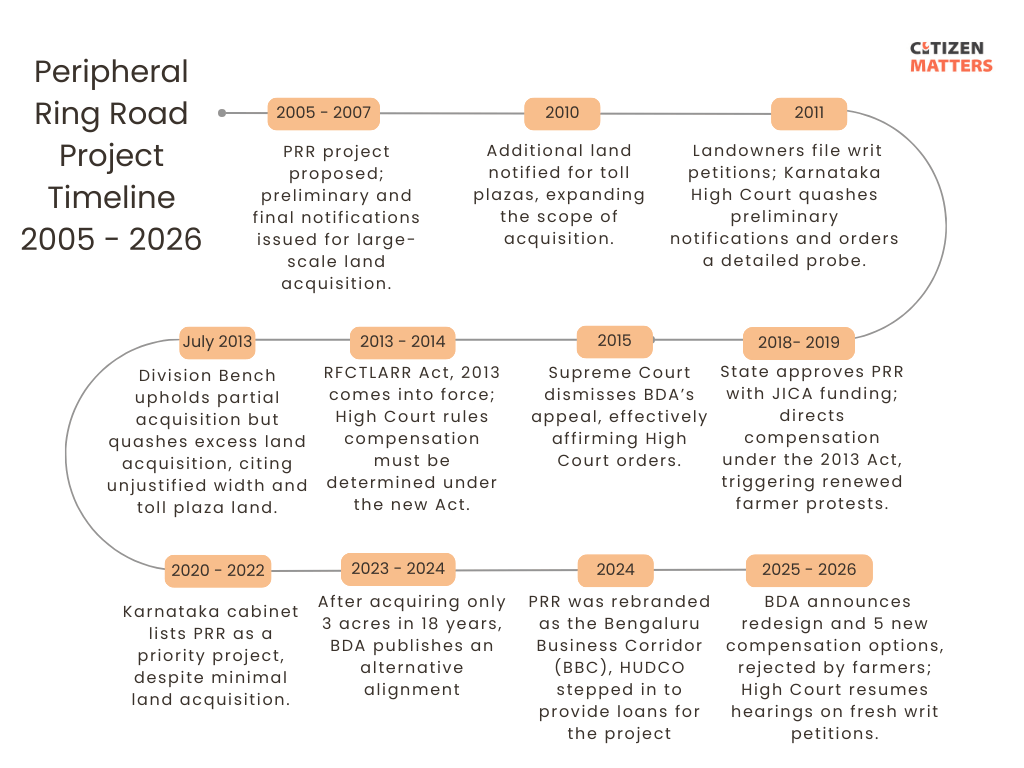

Between 2005 and 2010, plots of land belonging to nearly 14,000 families were notified for the project. Following this, several hundred writ petitions were filed by landowners challenging the acquisition.

While acquisition would mean displacement, landowners say the project has been troubling them in more ways than one since the notification. Once notified, the landowner is barred from any private dealings, including mortgaging, selling, or partitioning the land. Gopal was working at an automobile company in the UK and returned in 2016 after his mother fell ill. A few years later, she died of liver failure.

“The treatment was estimated to cost ₹40 lakh. If not for the restrictions on my land, I could have mortgaged it or sold a part of it for her treatment,” he says. He believes this might have saved his mother’s life.

Atheeq LK, the chairperson of the Bengaluru Business Corridor, told Citizen Matters, “When the project was notified initially, the government was not able to allocate funds for the project. In the past 16–17 years, the land rates have gone up significantly, which led to further delays. However, the project was expedited in 2023 and has progressed rapidly since, and landowners are coming forward to consent.”

Project is legally lapsed

Under the Bengaluru Development Authority (BDA) Act, 1976, as well as the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (RFCTLARR) Act, 2013, a scheme or project must be executed within five years of its official declaration. If not, the project is deemed to have lapsed, and the acquisition provisions become inoperative.

Farmers allege that the BDA failed to adhere to this requirement, allowing the acquisition to linger well beyond the stipulated period.

“The project is not lapsed,” Atheeq insists. “The road is incorporated in the Revised Master Plan of 2005, and so the land cannot be used for any other purpose. If it had lapsed, the Karnataka High Court would have closed the cases earlier. Also, land owners would not have given consent if the project had lapsed.”

Read more: PRR: Massive environmental damage for another futile Ring Road?

Unable to update crop information

Similarly, farmers are also unable to update information about their crops in the Record of Rights, Tenancy, and Crops (RTC) database. This means the crops and trees grown after the notification will not be considered for compensation. “We can’t get any government subsidies as we cannot register in RTC,” informs Gopal. “Farmers growing Ragi are also not able to sell the harvest to the government for public distribution through ration shops because of this.”

Now, the BDA has announced five different compensation options — cash payouts, developed residential plots in Dr K Shivarama Karanth Layout or layouts around PRR 1, floor area ratio (FAR) compensation, Transferable Development Rights (TDR)/Development Rights Certificate (DRC) or developed commercial plots under a 65:35 ratio (that is 8,385 square feet of developed plot per acre of land lost). However, most farmers reject all options.

“Essentially, the challenge is to arrive at a compensation that landowners feel is fair and worthwhile, while still remaining affordable for the government,” Ravichandar says.

The matter gets more complex as a recent news report mentioned that the PRR Raitha Haagu Niveshanadarara Sangha (PRR Farmers and Site Owners Association) plans legal action against the BDA. The group alleges that officials were misleading farmers with false promises and coercing them into signing “settlement” letters.

In the next part of the series on the Bengaluru Business Corridor project, we delve deep into how compensation mechanisms are manipulated, placing farmers at a disadvantage.

[Disclosure: V Ravichandar is a member of the Oorvani Foundation’s advisory board.]

I have taken a site in electronic city in 2015 and im unable to construct any house there due to notification, it was told that PRR1 will connect with Nice road but now congress governmentwants 2 roads run parallely in PRR2 both NICE and new road which is not required , so i let the govt to align PRR1 with Nice and extend NICE road on either side if required so that investing on PRR2 will be reduced, this is a basic common sense.

The given article is a good one explaining the pains of the Farmers and the effected site and house owners. Actually today’s TRAFFIC POSITION is same as it was 20 years earlier in ORR. It is not at all feasible to do with the PRR Project, as it will Congest. As STRR is already Functional and the Heavy Vehicle Traffic is being Diverted from STRR. No entry of Heavy Vehicle are there toward City. Hence, PRR project has to be Cancelled and it is not necessary, as Traffice has increased in these 20 years. My views🖐️🙏

As a concerned citizen, I believe infrastructure like the Peripheral Ring Road is important for Bengaluru’s long-term growth, traffic decongestion, and economic development. A growing city cannot survive without forward-looking planning.

At the same time, development must be just and humane. Land acquisition, compensation, environmental impact, and the concerns of local families must be handled with transparency and fairness. Progress should not create silent victims.

The government has the responsibility to plan boldly, but also to communicate clearly and act sensitively. Citizens, on the other hand, must engage constructively rather than react emotionally. If both sides work with accountability and mutual respect, projects like this can truly benefit the larger public without eroding trust.

Bengaluru deserves growth that is efficient, ethical, and inclusive.