Bengaluru’s water woes are not a secret to anyone, all thanks to the city’s water activists and environmentalists who have fought tooth and nail to promote Rainwater Harvesting (RWH) and sustainable water management in the city.

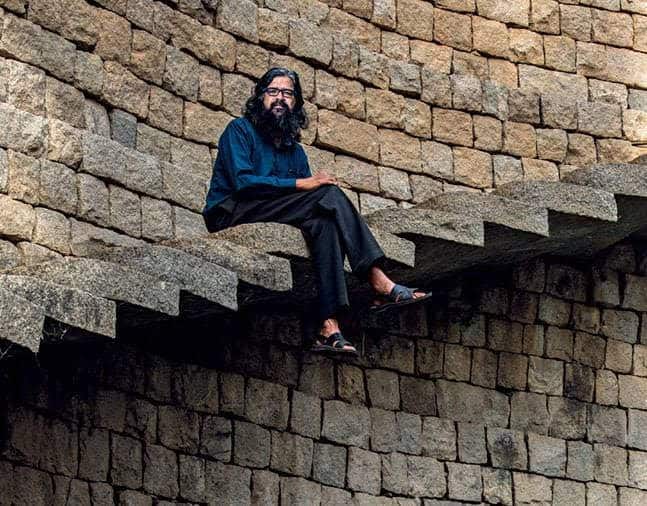

Two well known names campaigning for water sustainable are Vishwanath Srikantaiah and Shubha Ramachandran, both from the Biome Environmental Trust. Vishwanath is a water activist and an urban planner. He has worked in collaboration with the local communities to revive 10,000 wells with the support of the well-diggers, and helped in the development of 100,000 recharge wells. Shubha is a water sustainability expert. She has designed and implemented several rainwater harvesting and wastewater treatment systems in Bengaluru.

On the 12 year anniversary of Rain Water Harvesting being made mandatory in Bengaluru, we speak to them to get more insights about the challenges and opportunities of sustainable water supply in Bengaluru.

The Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) Act, 2009 declared that RWH systems are compulsory for all buildings built since 2009 measuring 1200 feet and above and buildings built before 2009 measuring 2400 feet and above. In the last 12 years, what have we seen in terms of RWH in the city? Have we seen the results we wanted?

Vishwanath: Close to 1,55,000 properties have RWH, according to the BWSSB, which makes it the second largest number of installations for any city in India, next only to Chennai. (Overall Bengaluru has around 20 lakh properties, with just 2 lakh properties mandated to install RWH, since the rule does not apply to properties smaller than 60×40 sq feet of ground area, built before 2009. BWSSB has 9 lakh domestic connections. Owners of around 45,000 properties are paying the fine. This means 1/13th of all properties have installed RWH. Note: apartments are counted as a single property unit in this calculation, since they have a single BWSSB connection.)

The city has also set up a RWH theme park in Jayanagar where people can go and get advice. We have trained more than 1,000 plumbers and well-diggers on RWH. Many large institutional buildings have done RWH, so that’s the positive side of it. If you look at the negative side, a lot more people could have done RWH. It would have helped the city a lot more.

Shubha: The earlier questions about water quality and if it is good enough to drink seem to be going away. That kind of water literacy has certainly been going up. For groundwater, we’re running this campaign now called a million wells. So the other part of RWH is taking surface run-off and trying to recharge groundwater with it, through recharge wells, which are the most economical and efficient recharge structures. I think time has come now to push that forward.

Read More: Two years, one lakh wells: Can ‘Million Wells’ movement help solve Bengaluru’s water crisis?

Role of citizens and our “can-do” spirit

How have we been able to do this? What has gone into making Bengaluru the city with the second largest number of RWH installations?

Vishwanath: One of the things that characterises Bengaluru is citizen engagement and citizen activism. This is a “can-do” city. I can only think of Pune and Bangalore as such cities in India, where there is active engagement with civic problems, solid-waste management, urban transportation.

Bengaluru is in an enviable position regarding water supply as compared to any other city in India because we got a million connections from the BWSSB. Every connection is metered, there is a volumetric pricing to the water and there is subsidy for domestic water supply. Where there is such good water supply, the tendency to look for alternative sources of water supply is not high. For example, Chennai (has the most distress) because there is a huge water scarcity and water was being shipped in tankers and there was no other source of water. In Bengaluru, the crisis is not yet dire. Yet, people have installed 1,50,000. That has to do with the culture of the city and that of community engagement with civic issues.

Shubha: For RWH, it could also be the distribution of water. Unlike Chennai or Bombay which receive very heavy rainfall for only 2-3 months of the year, we are fortunate to receive rain 6-8 months of the year. There are small incidences of rain, like the short rainfalls we had a couple of days ago.

One of the things that characterises Bengaluru is citizen engagement and citizen activism. This is a “can-do” city.

Vishwanath Srikantaiah

What have been the challenges to RWH?

Shubha: I think it’s this kind of inertia. The default option these days, if you don’t have good quality drinking water, you can order Bisleri, cans, and tankers. These market solutions are there. With RWH, all said and done, you would only get water when it rains if you are storing and reusing rainwater. There’s a need to maintain the system, especially at an individual house level. Even with the nature of groundwater, it is invisible. You recharge over a period of time and there are a lot of people who are extracting and you are not able to establish any direct correlation. It takes time for you to observe the results as well.

Vishwanath: All such endeavours need patience, perseverance, and a communication strategy which persuades the citizenry that they have to do something for not only themselves but also for the larger good. Now you can take the garbage and chuck it outside on the road and you are done with the problem. It is a community problem now. Similarly with RWH, you may have good water from the BWSSB. You may have a borewell which is giving you water. But unless all of us do RWH, the benefits will not flow. So, persuasion takes time.

Read More: How Bengaluru’s notorious ‘water tankers’ can be regulated

The state’s role in RWH

What are your thoughts on the state investing in RWH considering that the returns are invisible and long-term?

Shubha: The state can play a large role. Of course in the lands they own, they could do this. Even making it commonplace like having loans for implementing RWH. BWSSB also does these events like the Jala Rushi Puraskar contest which is given to the group that does these best practices. When there is acknowledgement from the Government, it is different from being acknowledged locally. There’s a lot of bottom-up movement that has been happening for this, we need the top-down happening as well.

BWSSB has also been convincing BBMP to amend building by-laws in such a way that no plan could be approved if it does not incorporate RWH. What would be the implications of this?

Vishwanath: BBMP’s jawabdari (accountability) is not with RWH or water supply. So, they have no benefits to gain if more people do RWH. There is no direct impact on BBMP. For the BWSSB itself, since it is not in charge of groundwater and it does not measure what benefit it gets from the water saved, there is no skin in the game. There is no real benefit. So, these laws will be in place but unless the citizens choose to do it on their own, it is unlikely that it will take off.

According to a survey published in 2019, South Bangalore has the most number of buildings which have not installed RWH yet. Why do you think this area has not shown interest in RWH?

Vishwanath: Two things. One, they have an excellent pipe-water supply so they never have a problem with Cauvery water. They have a good distribution. Second, they are blessed with good groundwater: open well and borewell water. Therefore, they don’t see the need for RWH. Whereas, it is the North and the East which are water-scarce and that’s where you see much more of RWH. So, the challenge now is to persuade South Bangalore to do it better because they can do it easily. In South Bangalore, you can dig a well, you can get water, you can recharge the water into the well, you can use the water, and become water-secure. So, a strong messaging has to go from the institutions and communities to pick it up.

Economic incentives for harvesting rainwater

What can be said about the trends in RWH in commercial/residential buildings?

Vishwanath: The commercial water is priced at Rs. 60/kl. BWSSB tariff is very high for commercial water use. Industrial water use is even higher – Rs. 72/kl. Domestic water is at Rs. 7/kl in the first slab, Rs. 11/kl in the second slab. So, in domestic use, if you save 100,000 litres through RWH, that’s 100 kl, which (works out to) Rs. 700. So, if you save 1 lakh litres of water in a year, the cost that will save you is only Rs 700.

Because the domestic pipe-water supply is so ridiculously subsidised in Bengaluru, while the production cost is Rs. 95/kl so there is no incentive for people to do RWH as an economic prospect. They can only do it as an environmental prospect. That is the problem with the domestic sector not picking it up. Commercial and Industrial sectors will pick it up because it saves them money.

Shubha: The offices and corporate buildings seem to have some systems in place. It may not be perfect or complete but some conversation is happening. With these smaller shops which are either rented or privately owned, there may be physical challenges like they may not even be taking Cauvery water for instance. They may be buying their own tanker water. Storing and reusing water may not be amenable to all of them as there may be a bunch of shops sharing a water source. There it has to be a group RWH implementation, making sure there is some contribution from everybody. For smaller shops, we really have to think about what is appropriate or how we don’t get stuck with the letter but go with the spirit.

It would be interesting to know from BWSSB that among all the connections, which ones are the commercial connections and what kind of commercial buildings are these. BWSSB can go a lot more public with who has done and who has not done. It is very difficult for us to go out and get this information. They already have it.

Domestic water supply is ridiculously subsidised, starting at 7 Rupees a kilolitre. Saving 1 lakh litre a year saves you a mere 700 Rupees. There is no economic incentive for people to do RWH.

Viswanath Srikantaiah

What about individual houses and apartment complexes?

Vishwanath: In the apartment complexes, there is the challenge of ownership. Who has to do it? The builder or the citizens’ association? For the builder, it’s a cost. So he cuts and scrapes and does a bad job and gets away. Not everybody but some of the builders. For the residents’ association, they have to run the whole damn thing. The enlightened residents’ associations do it and the others don’t.

Shubha: Apartment complexes in the peripheries are doing RWH because otherwise they pay Rs. 200 for 1000 litres of water. Especially for new ones that are being built, the big builders broadly put some infrastructure in place.

Read More: Rainwater harvesting: Apartment’s water bill goes from over a lakh to zero in monsoons

At what scale is rainwater harvesting the most convenient?

Vishwanath: It’s absolutely relevant from the smallest house to the largest industrial area. In an apartment, it does not make much sense, because in an apartment, the per capita roof area is limited, because you stack people up. If you have 40 square metre of roof area per person, you can be water independent in Bengaluru. If you store it and recharge it, that will be 100 litres per person per day. Now as an apartment, you tend to get only 4 square metre roof area per person. So it will only get you 10% or 15% of your total water requirement. It’s a supplement but it’s not a significant supplement. So, apartments don’t have an incentive to do it. Yet they do it. Why? Because they want to do it right and even that 10%-15% saves them money. Otherwise, they will have to buy from tankers or dubious sources.

BWSSB charges penalties to households who haven’t installed RWH. Has that been helping? Do households mind paying penalties?

Vishwanath: The cost of water is Rs. 7. Even if you double it and say Rs. 14, it will be dirt cheap. BWSSB is not interested in the water coming into the city. They are interested in money. So, they’d rather people pay the penalty than do RWH. So, there is a misalignment of interests here. This will be a game which will be played by people and institutions.

Shubha: Depending on the penalty, it would be a lot cheaper in the long run to install RWH and then benefit from it. It also needs to be one of the ways to ensure compliance. But, in many cases they just do something to get by. There’s another tricky part with RWH. You may have some infrastructure and not use it. The infrastructure may be broken or you may just have something to show the meter man that there is something in place, so you don’t have to pay the fine.

For certain cases, it might help to understand why people are not doing it and giving them an option. There are nuances that have to be considered. For example, we have been to apartments which are built on a quarry or on rocks. They’re not able to do groundwater recharge. They have no place to make a new sump. So, then is there any way out for them? Some engagement is certainly required for exceptions.

BWSSB can go a lot more public with who has done and who has not done. It is very difficult for us to go out and get this information. They already have it.

Shubha Ramachandran

Isn’t the BWSSB spending a lot of money in transporting the water from Cauvery to Bengaluru?

Vishwanath: It is Rs. 95 / kl. But, there is a political unwillingness to charge. BWSSB puts up proposal after proposal for revision of water tariffs and it’s rejected or held up. No action is taken. So, what BWSSB does is take money from new buildings saying that, “We will give you connection as and when water is available”, takes that up-front cost, puts it into their kitty and spends it. You pay Rs. 1.5 lakh in some apartments to get a connection, which is ridiculously high. That’s how BWSSB’s finances are getting mismanaged with great skill.

Here’s the other side of the story: Let’s say I have a well in my house. Let’s say the well is dry. Now I do RWH and I put it into the well. The well springs back to life with water. I start using the water. You’d think the BWSSB should reward me for doing that for being independent of the city utility. Every 1000 litres that I use from the well, I save BWSSB Rs. 88 (95-7). But, what the BWSSB does, is penalise me. It charges me Rs. 100 / month for the well water.

I’ve taken it up with BWSSB and we’re working out a solution for it, to separate open wells from the dug bore-wells, so that if you do RWH and use open well water, you will not be charged the sanitary cess. Even at the nitty-gritty level, we have to look at the alignments and misalignments.

Shubha: BWSSB can do something pro-poor (like Delhi has done). They make sure that a minimum amount of water is free. Even we already have a step-tariff but perhaps we could go a lot steeper once we exceed a certain number. The first slab of 20,000 litres per family could be priced reasonably as it is right and beyond that, you can increase the tariffs to make it more sensible to do RWH. But, yes a certain amount of water needs to be given to everybody at a reasonable price and you can’t really have differential rates because it becomes a lot more complicated to implement.

How do we convince the apartment complexes which have been mushrooming all around in Bengaluru to take up RWH?

Vishwanath: One of the challenges to apartment complexes is the masterplan and building bylaws do not protect aquifers. What we do is we dig basements for car parking and we pump out water from these basements and throw it out into the drains when we are building these large apartments. Next to Mount Carmel College, next to Mekhri circle, apartment complexes have pumped out water for 6 months to 8 months to drain the aquifers. When you build the car parking, there is no capacity for the aquifer to hold on to rain water. The whole sponge is gone. We have to rethink our masterplan and building bylaws to be in alignment with the water requirement in the city.

Do you see the political unwillingness to disincentivise Cauvery water going away anytime soon?

Vishwanath: No. Which is why in Bengaluru we appeal to the democratic sense of people for participation. In Chennai, it was the danda by Amma. Jayalalitha said, “In 6 months if you don’t do it, I will cut off your water supply connection and your sewage connection.” In Bangalore, we have the time to do it. We don’t have to kill ourselves in enforcing RWH. At the same time, citizen groups are reviving lakes which will recharge the aquifer. There are different scales at which RWH will happen and we have to push each scale.

What can BBMP do to help with this effort?

Vishwanath: It can redesign the stormwater drains better. Instead of taking all the water and barrelling it out outside the area, it could make infiltration wells in the smallest drains and develop a masterplan for all drains to have recharge wells.

Do you see this happening anytime soon?

Vishwanath: Yes, a lot of politicians have taken interest in Koramangala, BTM Layout, I think Jayanagar also. MLAs can push for the stormwater drains to have percolation pits. Now, we have to bring it into the guidelines and the manual of design for the stormwater drains

What now for Bengaluru? How are we to make our water supply more sustainable?

Vishwanath: Now what we have to do is democratise the governance of water. Every ward committee must make sure that there is a discussion on whether there is universal coverage. 100% of all the buildings in that ward, do they have water and sanitation connection? If they don’t, how soon shall we get it to all of them? Then, how do we facilitate all the citizens to do RWH in the cheapest and easiest manner as relevant to that ward. Then, it has to revive all its lakes and it has to fill it with treated wastewater like Jakkur and Doddabommasandra is doing.

At an institutional level, BWSSB will have to expand itself to have a groundwater cell. There are 400,000 or more borewells. God only knows who is managing them. There is a Groundwater Authority which is very poorly staffed. We need to strengthen groundwater governance and make it more participatory. We need to make a wastewater management plan.

Finally, the city completely depends on the Cauvery for all its requirements. It will have to invest in the forests of Kodagu, make sure that the catchment is maintained. Whenever we open the tap, it’s the Cauvery flowing. We have to make sure that Cauvery continues to flow. Sand-mining, deforestation, and pollution cannot happen in Kodagu.

Whenever we open the tap, it’s the Cauvery flowing. We have to make sure that Cauvery continues to flow.

Vishwanath Srikantaiah

As a city, what can we teach other cities and what can we learn from other cities?

Shubha: We have this website called urbanwaters.in. We already have Bengaluru on it. Now, we are trying to add other cities. There is Tumakuru. Fairly shortly, we should have Hyderabad and some of the other cities. That is a good first step to share our best practices, case studies, and contact information with other states and cities. Chennai seems to be running its wastewater treatment plants rather very well. A lot of energy is required to run a waste treatment plant. The Sewage Treatment Plant (STP) generates the electricity that is required to run itself. It may be a technological solution but that seems to be something we could see and learn from them.

Your article on RWH is educative and good. Please advise whether we have to advise BWSSB about availability of RWH in an apartment as soon as it is created

Whether BWSSB reduces it’s charges in their monthly water bill charged by them which includes some penalty charges towards our bore well. Please advise whether we should advise BWSSB about existence of RWH in our apartment

I’ve seen people taking BWSSB for a ride. Many take Photos from elsewhere / bribe and get away .There should be an audit house to house done one time.I doubt the figures published by BWSSB.

Please advise whether BWSSB gives any concession in their water charges bill issued by them on monthly basis for the RWH system introduced by us in our apartment. We hava a borewell and RAIN WATER HARVESTING done last year. Whether we have to advise BWSSB that we have a RWH. Please advise

What if rain water is channelized directly into bore? Will it affect bore pump or bore? Mail address of Shubha mam and Vishwanath sir may be shared for further advice on this subject.

More than 80% of rain water is going waste in roads,… This needs to be addressed by Govt by installing RWH system in all road corners to harvest rain water…