In the run-up to the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) elections scheduled before the end of this calendar year, Bengaluru’s civil society organisations are getting more active to highlight civic issues that need urgent attention. As a first step, on June 24th, the Civil Society Forum (a coalition of civil society groups based in Bengaluru) submitted its “Manifesto for Development of Bengaluru in next five years” to senior representatives of political parties.

The manifesto does not pull any punches. When it says, for instance; “Local self-government, with transparency, accountability and people’s participation, as envisaged in the 74th Constitutional Amendment (CAA) for urban local bodies stands vitiated in Bengaluru with the State government and MLAs usurping the role of the local government. People’s representatives and officials at local level, abdicating their constitutional obligations, are engaged in massive corruption resulting in large-scale encroachments of public lands, violations of zoning and building bye-laws, pollution of land, water and air in the city and deterioration of the quality of life of the citizens…. Basic entitlements of citizens to food, water and sanitation, housing, health, education, employment, and social security have been neglected. This is an opportunity for all political parties to demonstrate their commitment to the citizens of this city and restore Bengaluru on the progressive path by ushering in genuine, honest pro-people policies.”

That the powers-that-be have no concern for the citizens who vote them to power and bank-roll them by paying taxes was brazenly demonstrated just a couple of days earlier when Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Bengaluru.

Under direct orders from Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai, multiple agencies—BBMP, Bangalore Development Authority (BDA), and Bengaluru Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. (BMRCL)— worked on a war footing to redo road stretches in the city and fill up the potholes for which Bengaluru has become notorious.

Residents of the city had for months been running pillar to post to get these stretches fixed, but to no avail. But the Prime Minister’s visit for just a few hours saw several crores spent with a sudden spurt of activity with hundreds of labourers working day and night.

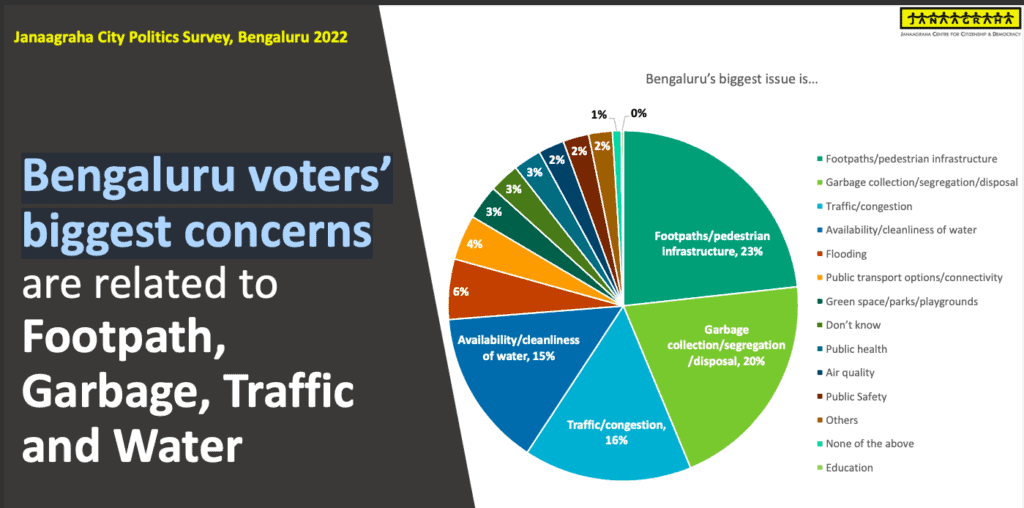

Bengaluru voters’ biggest concerns

Recently, Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy conducted a survey that brought out issues that most bothers Bengalureans and revealed their mood.

- For 23% of urban poor, their biggest worry is access to water. With Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) closing public taps in slums and irregular supply to taps that remain, the poor are being pushed to rely on costly RO plants for drinking water. Another issue that dominates the concerns of the urban poor is garbage, probably owing to irregular collection of waste from the poorer pockets in the city.

- Expectedly, 30% of the middle-and-upper-class respondents said their biggest concern has been traffic.

- However, cutting across all classes, lack of pedestrian facilities has emerged as one of the biggest pain points in the city with 23% of respondents listing it as a concern.

- Followed by :

- Garbage (20%)

- Traffic (16%)

- Water (15%)

- The survey further revealed that 83% of Bengaluru voters want the BBMP elections to be fought on the basis of civic issues they face in the city.

- The dismal state of grassroots governance was revealed from the fact that a majority of citizens approached MLAs and MPs for grievance redressal, with only 12% approaching a councillor.

- 88% of the respondents had never met a city councillor.

- The survey also revealed more than half of the voters (52%) do not recognise wards as the basic unit of governance.

- 87% of the respondents are not even aware of ward committees.

However, the redeeming feature of the survey is that though many lack awareness and connect with civic governance, first-time voters evinced a keen interest to engage with civic polls. An overwhelming 86% of them strongly expressed their intention to cast their vote in the upcoming civic polls and 88% of them believe strong local governance is the key to a better future of the city.

This limited survey clearly brings out one fact – that there is hunger among citizens for a participatory grassroots city governance. There is none at present with the entire system being controlled by the bureaucrats, MLAs, ministers and chief minister who are not elected for the purpose.

This is because urban governance in Bengaluru does not have an inclusive urban philosophy and politics. What is happening is just urbanisation making the city a ‘brick & mortar real-estate’ entity rather than a vibrant human settlement.

Read more: Effective participative governance requires corporators at the helm of ward committees

Bengaluru lacks urban advantages

Bengaluru being an ‘engine of economic growth’ needs vibrancy if democratic and participatory decision making is to take place. For this to happen, the philosophy of urbanism should be adopted accompanied by urban politics and leadership capable of understanding this and taking it forward.

Jeb Brugmann (2009) defined ‘Urbanism’ as “a way that builders, users and residents co-design, co-build, co-govern and combine their activities to support ways of production and living that develops their shared advantage.”

‘Urban shared advantages’ are the basic elements that make cities ‘magnets of productivity and prosperity’–or economies of density, scale and association. Density is the concentration of people and their activities that enhances the efficiency of any economic activity being pursued. ‘Scale’ is the increase in the volume of any particular opportunity, producing what we call ‘economies of scale’ that makes activities attractive or services profitable.

The scale and density of interactions among people with different interests, expertise and objectives then combine to create the third basic element – economy of association that exponentially increases the variety of ways and efficiency with which people can organise, work together, invent solutions and launch joint strategies for urban advantage. Bengaluru does not get the leverage of these urban advantages to the full because it does not practise urbanism of inclusive and shared development.

Time for reforms in city governance

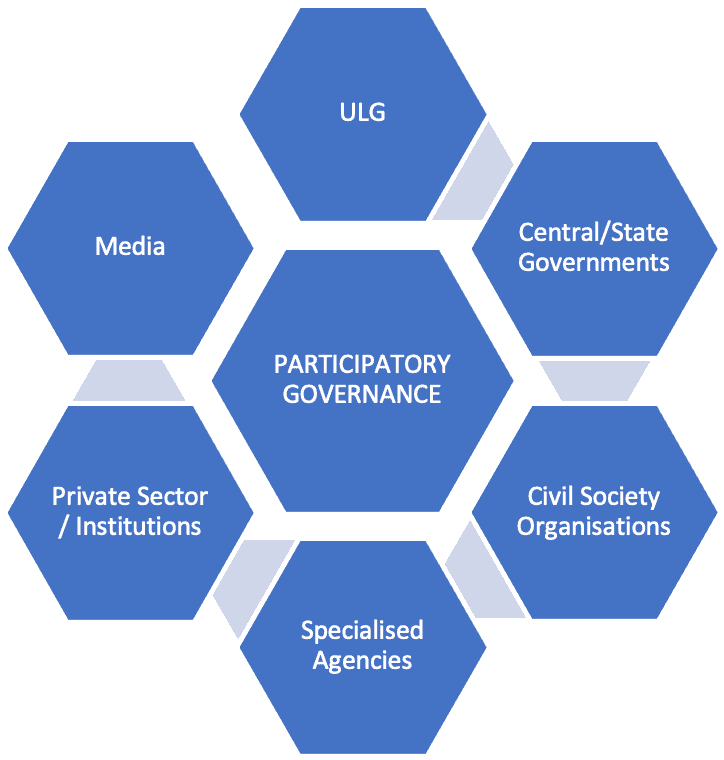

Strengthening democratic and participatory practices in local governance gets people closer to government, which helps them in guiding public institutions, policies and programmes. People’s participation expands public spaces, enhances the relationship between society and government, gives greater legitimacy to democratically elected authorities, promotes respect for citizenship rights, enhances the quality of politics and strengthens solidarity and cooperation. Through this process, grassroots and knowledgeable leadership can emerge that can take dynamic urban governance forward.

When citizens’ groups and civil society are mobilised and organised in a systemic way, they are in a better position to identify issues and challenges and also assess gaps in the governance system especially with regard to service delivery (through community monitoring and use of social accountability tools).

This increased demand on the part of citizens for effective and accountable governance leads to the adoption or improvement of social accountability mechanisms, like citizen charters, information disclosure and grievance redressal systems with the government machinery actively cooperating. This form of participatory decision-making can form the base for emergence of good political leadership which is woefully lacking now.

This was the intention of CAA-1992 under which Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) were to be transformed into Urban Local Governments (ULGs) which would perform the key tasks assigned under the 12th Schedule (Article 243W): Urban planning and development; land-use and construction; economic and social development; roads and bridges; Water supply; Public health and sanitation conservancy; Urban forestry and environment protection; safeguarding interests of weaker and handicapped sections of society; slum improvement and upgradation; urban poverty alleviation; provision of urban amenities and promotion of cultural, educational and aesthetic aspects.

This has failed to take off because a pragmatic brand of urban politics has not emerged to take this agenda forward. Such politics that could urge governance reforms to give more autonomy, financial powers and professional capacity to ULGs is an urgent imperative if urban quality of life and delivery of services are to improve.

Time for a urban local politics and government

Urban politics should encompass participatory urban governance that would include the ULG, the private sector and civil society. All three are critical for sustaining human, economic and social development. City government creates a conducive political, administrative, legal and living environment. Private sector promotes enterprise and generates jobs and income. Civil society facilitates interaction by mobilising groups to participate in economic, social and political activities. It also resolves conflicts. Because each has weaknesses and strengths, governance is brought about through constructive interaction among all three. In short, urban politics should treat city governance as a joint-venture.

If there is one metropolis in India where such urban politics can evolve leading to participatory city governance, it is Bengaluru because it has the necessary wherewithal for that. Steps in this direction started in 1999 with the formation of the Bangalore Agenda Task Force (BATF) piloted by the then Chief Minister S M Krishna. It was headed by former CEO of Infosys Nandan Nilekani and included K Jairaj IAS (member secretary), Dr Rajaramanna, Dr Samuel Paul, Naresh Narasimhan, Kalpana Kar, Ramesh Ramanathan, V Ravichandar, Suresh Heblikar, Anuradha Hegde and late Dr H Narasimhaiah, all prominent names in the urban space.

Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy, founded by Swati Ramanathan and Ramesh Ramanathan has been active since December 2001 with the objective of transforming the quality of life in cities and towns. Their task is to catalyse active citizenship in city neighbourhoods and with governments to institute reforms to city governance. Civic Learning, Civic Participation and Advocacy and Reforms are Janaagraha’s three major strands of its work.

Then there is Bangalore Political Action Committee (B.PAC), a non-partisan citizen’s group that aims to improve governance in Bengaluru and to enhance the quality of life of every Bengalurean. B.PAC is specifically targeting good governance practices, integrity and transparency in all arms of the government, improving the quality of infrastructure in the city and identification and support of strong candidates for public office at all levels of governance.

In 2014, Karnataka government set up a three-member BBMP Restructuring Committee with former Chief Secretary B S Patil as chairman and ‘civic evangelist’ V Ravichandar as member. In its report submitted in July, 2015, the committee recommended structural changes in the BBMP and also a three-tier system in Bengaluru for efficient governance. It submitted another report in 2018 covering various governance issues along with a Draft Greater Bengaluru Governance Bill.

In 2016, Bengaluru Blue Print Action Group (BBPAG) was formed with Chief Minister Siddaramaiah as chairman that had eminent citizens like Infosys Chief Mentor N R Narayan Murthy, Wipro Chairman Azim Premji, Ramesh Ramanathan, Swati Ramanathan, Biocon Chief Kiran Mazumdar Shaw, and other urban experts and professionals. This was, however, challenged in the High Court and did not take-off.

Continued struggle for people’s voices to be heard

Despite all these efforts, participatory city governance has not happened in Bengaluru. Due to the severe flaw in the original Constitution providing only centralised two-tier governance (Centre and States), decentralised local politics never matured in India.

The grafting exercise of the 74th Amendment in 1992 also did not help and hence the continued struggle and cries by the people for their voices to be heard. Giving people-centred urban politics shape and substance is the task cut out for Bengalureans on the eve of the forthcoming civic elections.