COVID-19 has caught us all unawares, but in the last few weeks Bengaluru has sprung on its feet to tackle the crisis. BBMP has set up a war room to centrally oversee the situation, police are working overtime, and so are hospitals and medical staff. Besides, innumerable citizens are doing their bit to distribute money, medicines, food and other essentials to those in need. It’s heartwarming to see how the city has come together yet again.

But what we have now is an adrenaline-filled system – both formal and informal – that’s working overtime, doing whatever it takes to cope with the crisis. Centralised emergency systems are not built to last – just like war-time measures – as they cannot be stretched beyond a threshold without repercussions. These emergency setups also override existing norms, protocols and systems we take for granted in a democracy. Further, due to constant resource constraints and other challenges, they cannot cater to all needs or even everyone’s needs.

Yes, we need all hands on deck to help existing systems tackle new threats, but we also need to quickly learn and adapt to our future needs in this new ‘normal’. It is anyone’s guess how long we will have to deal with COVID-19, but the effects of the lockdown on public health, economic growth and livelihoods are likely to remain for several months or longer. Many sections of society are going to be severely set back – for some this may be temporary, and for others, permanent.

A recent study from the University of Cambridge shows that the lockdown in India needs to be extended to 49 days so as to effectively contain the virus spread. Even in case of a phased withdrawal of the lockdown, the daily concerns of managing food, medical emergencies, supplies, etc, will be prolonged for many vulnerable people.

Ward committees can make the problem easier to handle

With increasing uncertainties, perhaps the answer yet again is to strengthen our decentralised systems of governance – ward committees.

Even the National Disaster Management Plan (2016) states the following among its objectives:

- the need to strengthen disaster risk governance at all levels from local to Centre

- empower both local authorities and communities as partners to reduce and manage disaster risk

- promote the culture of disaster risk prevention and mitigation at all levels

Working at the ward level would help break down the scale of the problem to make it easier to handle, and make our systems more inclusive, optimised and responsive to people’s diverse needs. Moreover, it is about establishing a system rooted in the local community, in care, compassion and cooperation, rather than strict adherence to rules at whatever cost.

Ward committees have a mandate to ‘establish Disaster Management Cells in each ward’, but these Cells have never been set up in Bengaluru. They are however, ripe as an instrument to take on the current crisis. As per a 2016 notification of the UDD (Urban Development Department), “The paramount goal of disaster management activities is to reduce, as much as possible, the degree to which a community’s condition is worsened by a disaster relative to its pre-disaster condition.”

In the absence of any guidelines, stated below is a possible guideline structure with which Ward Disaster Management Cells (WDMCs) can be set up immediately.

Seven potential functions of a WDMC

- Strategy and Planning

The National Disaster Management Plan already gives the framework for a disaster management cycle – preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation. All these stages are relevant in the ongoing crisis, so as to ‘flatten the curve’ – as the virus has not hit every place, there is a need to suppress its spread where it has; and to also set up systems to stop a resurgence in the weeks after the lockdown.

| Four phases of disaster management | Examples of corresponding tasks for WDMC during COVID-19 outbreak |

| Preparedness: Activities undertaken in the short term before disaster strikes, that enhance the readiness of organisations and communities to respond effectively. |

|

| Response: Activities undertaken immediately following a disaster, devoted to reducing life-threatening conditions, providing life-sustaining aid, and stopping additional damage to property. |

|

| Recovery: Short-term and long-term activities undertaken after a disaster, that are designed to return people and property to at least their pre-disaster condition of well-being. |

|

| Mitigation: Sustained activities undertaken in the long term after one disaster and before another strikes, that are designed to prevent emergencies and reduce damage. | Putting in measures to stop resurgence of COVID-19:

|

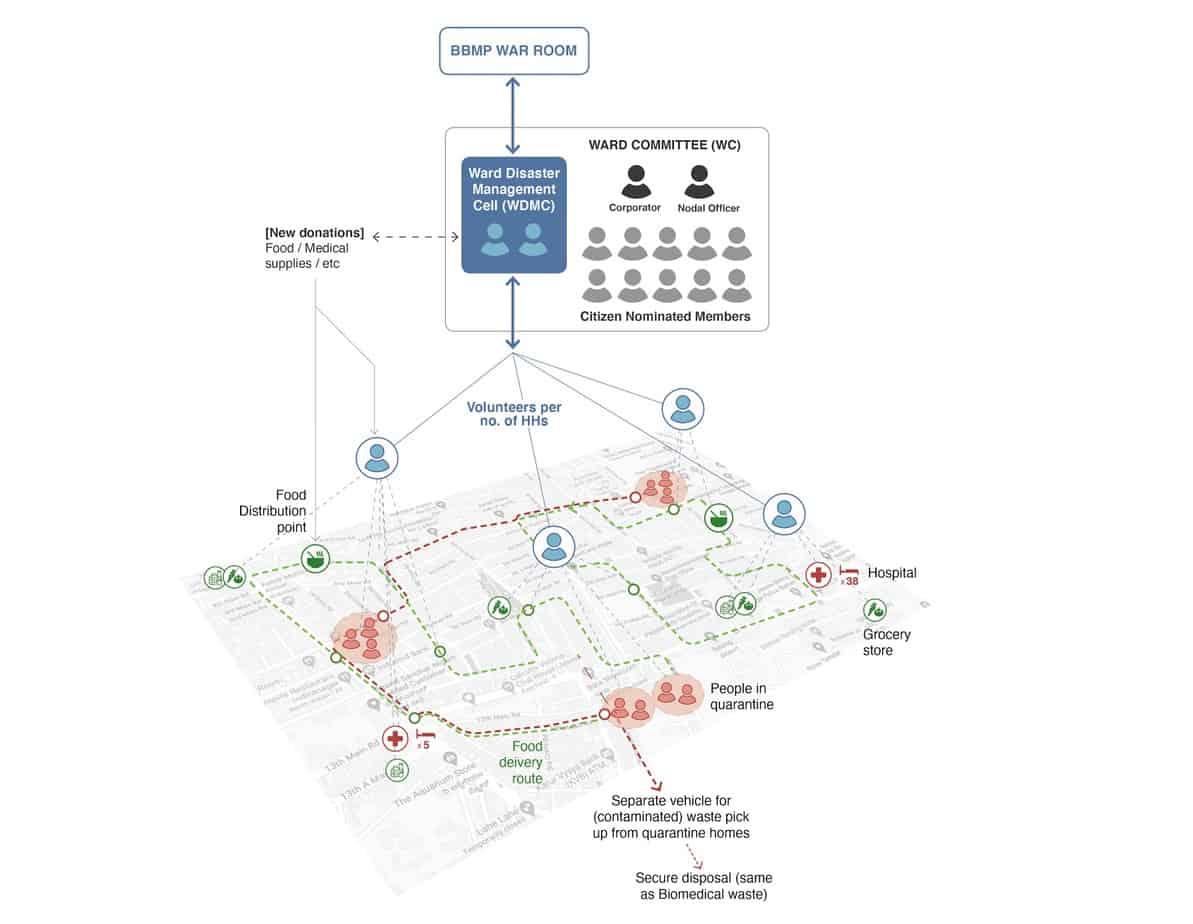

- Recruitment and training of volunteers

There is a need for community-based volunteers who can be eyes, ears and logistic support on ground. The volunteer network could be modelled on the Suraksha Mitra community policing programme. However, the number of volunteers need to be quantified and allocated on a per-number-of-household basis, and not ward area. This is because ward sizes differ drastically.

Training of volunteers may include:

- Use of safety equipment and compliance protocols for food distribution

- Mapping and regular updation of data on availability of essential services

- Collation and reporting of on-ground needs in actionable formats

- Communication of protocols to be followed by people

- Community policing

- Coordination

WDMC is to be a single-point local contact for the BBMP war room, local hospitals, police and other emergency services as well as local community volunteers and citizens (top-down and bottom-up coordination).

- Collation and validation of on-ground requirements

WDMC should coordinate with community volunteers to vet on-ground reports from citizens or government agencies in order to map requirements and ensure their accuracy. All local information is to be digitally accessible to the WDMC through a neighbourhood/community portal, to aid planning, coordination and prioritisation of action. This is estimated to drastically reduce ambiguity, chaos and duplication of efforts.

Data points to include:

- Tracking spread of coronavirus patients

- Quarantined individuals, buildings, areas

- Tracking food supply pipelines and demand areas

- Location of vulnerable people and their needs (older people, people with ailments, urban poor, migrant workers etc)

- Timings and availability of essential services (grocery shops, chemists, doctors, hospitals etc.)

- Information and communication

WDMC, through its volunteer team, is to be the one-stop shop for disseminating authentic, live, relevant information for people in the ward.

- Channelising local funding and schemes

Ward committees already have a mandate ‘to mobilise voluntary labour and donation by way of goods or money for implementation of Ward Development Scheme and various programmes and schemes of Corporation’. This may be leveraged to channelise local philanthropy towards specific needs in the neighbourhood – for residents, for PPE kits in hospitals etc.

Another mandate of ward committees is to approve the list of beneficiaries for Corporation’s schemes. WDMC can help identify those who are entitled to any new scheme of the Corporation to remedy the effects of COVID-19, such as UBI, food benefits etc.

- Identifying and allocating infrastructure as temporary disaster relief centres

This may be towards storage of medicines, food, clothing supplies, community kitchens or even safe temporary shelters.

Diagram of proposed structure of WDMC. Credit: Sensing Local

WDMC team

WDMC should have a core team of at least two full-time personnel to work alongside ward committee members, to handle the seven core duties proposed above.

WDMCs can be set up right away

Of the 198 wards in Bengaluru, only 70-80 have functional ward committees that conduct meetings. And of these, only 15-20 are highly active and involved in planning and decision-making beyond grievance redressal. WDMCs need to, and can be, set up right away to avert further distress to citizens, and to plan ahead systematically. Where ward committees are absent or weak, the corporator can anchor the WDMC.

Once put in place, WDMCs can strengthen the capabilities of the ward committees to deal with not just COVID-19, but also other crises like natural or climatological disasters.

This proposal reflects the ongoing discussion at Sensing Local as well as our personal experiences from the response to COVID-19 at the local level. Setting up effective WDMCs require collaboration and consultation with several stakeholders surrounding the COVID-19 response – individuals, community networks, civic organisations, government, and so on. Sensing Local is open to curating this discussion.

Hats off to you.this is exactly and the most life saving planning i have ever read..and thinking. How to fight against corona virus. Because We don’t now how dangerous virus spred.i think we have to Stop this virus. From home to area.to locality to LOCALITY. To city to States to COUNTRY..am really thankful to know that ur the future off the planner..than you . And will share this as much as i can..i hope someone somewhere in this city can opt this plan. And start this…..