The residents of Electronic City, which is not even within BBMP limits, are becoming guinea pigs for the Palike’s misguided attempts at ‘scientific waste management’. BBMP has signed an agreement to set up an incineration-based Waste-to-Energy (WtE) plant at Chikkanagamangala, a stone’s throw away from Electronic City.

Problems with the existing plant

The project is coming up at a site that currently houses a composting plant running under BBMP’s direct supervision. This plant processes wet waste from 44 BBMP wards. Operational since May 2018, it soon led to stench and fly menace in the locality. Last July, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) even issued directions that the plant should stop accepting mixed waste. Even after this, there has been no respite for us residents.

To add to our worries, on April 25, 2019, BBMP signed a 30-year agreement with the Indian subsidiary of a French company 3Wayste, to convert the existing composting plant into a WtE plant.

On January 19, 2019, three months before the contract was signed, a stakeholder workshop was conducted. According to a presentation shared at the event, 3Wayste is an environmental technology company that emerged out of a family-owned recycling business set up in 1991, in Le Puy-en-Velay, France; and has operations globally, with many projects under development.

What is the new project all about?

WtE plant is the general term used for plants that burn waste to generate electricity. These plants are supposed to burn only the segregated, high-calorific portions of waste (excluding wet waste and recyclables).

The plant to be set up in Chikkanagamangala is meant to process 500 tonnes of mixed waste daily – BBMP is expected to supply 300 tonnes, and the plant has to gather the remaining 200 tonnes from other sources. The waste is to be segregated into wet waste, recyclable plastics, and combustible plastics. These three categories of waste will be composted, recycled and burned for energy generation, respectively.

In addition to Chikkanagamangala, BBMP has proposed setting up WtE plants in four other locations in the city. In an earlier article, I discussed why incineration-based WtE plants, in general, are poor solutions for waste management in Bengaluru.

In this article, we point out glaring issues with the proposed Chikkanagamangala plant. As residents of the locality, we pose these questions to BBMP, as their misstep that will not only affect our neighbourhood but will also sound the death knell for sustainable solid waste management in Bengaluru.

1) Why did BBMP entrust the incineration process to a company that has no experience in it?

As per BBMP’s contract with 3Wayste Bengaluru Pvt Ltd, the plant is expected to process around 500 tonnes of waste daily. Copy of the contract had been accessed by the NGO Environment Support Group through an RTI application to BBMP. Also, the plant has to generate 9.2 MW of electricity daily, as mentioned in a presentation made by the company.

3Wayste currently operates a waste segregation and sorting unit at Le Puy-en-Velay in Haute-Loire, France. This seems to be the company’s sole working facility. After their first plant there burned down, a new plant was inaugurated in December 2018. G Parameshwara, the then-Deputy CM of Karnataka had attended the inauguration.

Parameshwara’s trip was meant to study the capabilities of 3Wayste as well as SWM practices in France. Incidentally Randeep D, the BBMP Special Commissioner for Solid Waste Management (SWM), who is in charge of SWM in the city, was not part of the delegation to France.

3Wayste’s plant in France only has the mandate of waste segregation and resource recovery; it’s not a WtE plant. It segregates mixed waste, and then generates compost out of wet waste, extracts recyclables, and generates Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) from combustible waste. RDF is generally used as fuel in cement plants; 3Wayste does not burn RDF or generate electricity from it.

As per 3Wayste’s website, the only actual WtE implementation that the company has approval for is in the French territory of Reunion, which is a sparsely-populated island in the Indian Ocean. As per the website, this facility is scheduled to be operational only in May 2020.

From this, it seems like BBMP has entrusted the project to a company that has no experience in running WtE plants, but only in segregation and waste processing.

When the members of E-City Rising met a senior BBMP official, he mentioned that 3Wayste is looking to partner with a technology vendor for the incineration process. But there’s no mention of a ‘third party’ technology vendor in the concession agreement itself. Given the critical process here is incineration, shouldn’t that be part of the core expertise of 3Wayste itself?

2) Why sign the contract when the company was not even incorporated?

BBMP signed the concession agreement with 3Wayste Bengaluru Private Limited, the Indian subsidiary of 3Wayste, on April 25th, 2019. The then-Deputy CM of Karnataka, G Parameshwara, had signed as witness to the agreement.

However, 3Wayste Bengaluru had not been incorporated at the time. Central government’s Ministry of Corporate Affairs website reveals that it was incorporated only about one-and-half months later, on June 6, 2019. In spite of this, the Urban Development Department ratified the agreement, according to a news report in the Deccan Herald.

3) Why is the plant being set up so close to habitation and several companies, when WtE plants are known to cause pollution?

According to the Central Pollution Control Board, the burning of municipal solid waste is known to cause high levels of exposure to persistent organic pollutants like dioxins and furans. This, in turn, can cause cancer and other long-term health impacts on residents nearby.

Around the Chikkanagamangala project site are several villages, colleges, companies, orphanages, old age homes and residential units. The closest residential units are within 50 m of the plant site. And 900 m away is Electronic City, where lakhs of employees come to work.

They are already affected by the stench and odour caused by the malfunctioning composting plant. It will be foolhardy to assume that they will not be affected by a WtE plant.

Absolutely. And to make it worse BBMP has signed a contract to convert this poorly run SWM plant to a WTE plant. Will ELCITA & others take preventive action or wait for irreversible damage to environment and health of residents / employees? #LetECityBreathe #RightToBreathe https://t.co/nqHseQgzZS

— Ranjesh Hebbar (@RanjeshHebbar) November 8, 2019

India’s pollution thresholds – as mentioned in the SWM Rules 2016 – are already significantly more relaxed than say, Europe. (Find a comparison of emission standards in India and Europe here.) But the impact of pollution would be much higher in a densely-populated country like India than in Europe.

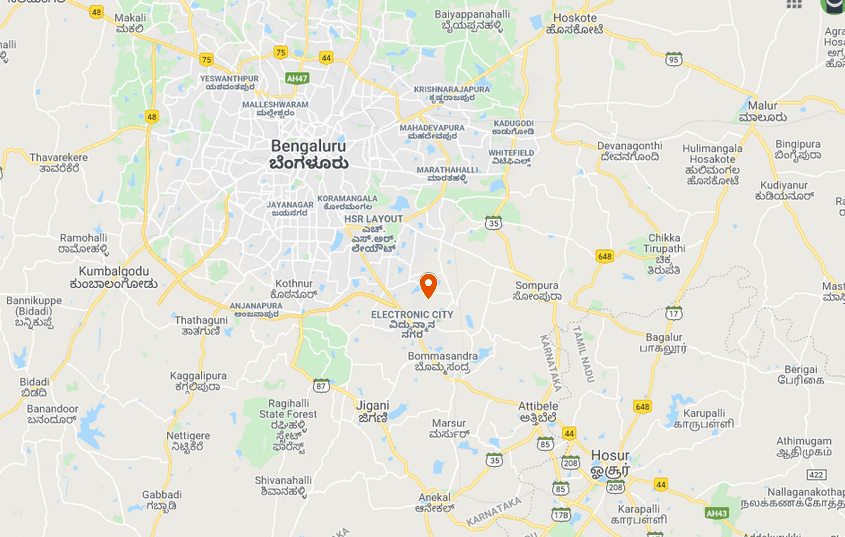

The Chikkanagamangala project site is located outside BBMP limits, near Electronic City.

Should the lives of so many people be put at risk, is a question for BBMP to answer. Just because the area is in the panchayat limits does not absolve BBMP of its responsibility towards people there.

Worse, as per Clause 5.10.1 in the current agreement, 3Wayste can landfill at the site. Additionally, clause 5.10.2 stipulates that 3Wayste should not request BBMP for an additional landfill site within the first 10 years of the plants’ operation. This could lead to rejects getting dumped around, affecting groundwater and habitation, as has happened in the case of WtE plants in Delhi.

Besides, as discussed in my previous article, WtE plants are not apt for processing the content of municipal waste generated in India. These plants have consistently failed in the country too.

As per SWM Rules, 2016, WtE plants can only burn the segregated non-biodegradable non-recyclable high-calorific portion of waste, along with rejects from the composting process (about 40% of composted material usually turn into rejects).

This means, given the usual composition of municipal waste in India, less than 200 tonnes out of the 500 tonnes of waste available to the Chikkanagamangala plant daily, can be used for incineration. Given this, the plant would not be financially viable.

In sum, we residents are concerned the plant will spell doom for the air quality of much of Bengaluru’s IT corridor. To save residents, villagers, and companies in the priced Electronic City, we urge BBMP to shelve the plan and scrap the current agreement immediately. BBMP should pursue segregation at source and decentralised waste processing on a war footing to solve the garbage crisis, rather than resorting to unviable and unsustainable methods such as incineration-based WtEs.

[Disclaimer: This article is a citizen contribution. The views expressed here are those of the individual writer(s) and do not reflect the position of Citizen Matters.]