On 7th September 2017, a 7-year-old school-going child was run over by a school bus while he was trying to cross Old Madras road (OMR). He was rushed to the hospital in an auto-rickshaw. The doctors examined the boy, and proclaimed that he suffered severe head injuries and had died on the way to the hospital.

On 14th March 2017, a male pedestrian, 45, was hit and run by an unknown vehicle near Battarahalli junction on OMR when he tried to cross the road. He too sustained serious injuries and died on the way to the hospital. In another three months, a female pedestrian, 55, died on the same spot after being hit by a speeding car. In June again, this spot claimed the lives of three pedestrians who were hit by a speeding motorcyclist.

These victims were among the 282 pedestrians killed on Bengaluru’s roads in 2017. Of the top eight metros in India, Bengaluru continues to have the third highest number of pedestrian deaths annually.

An analysis of Bengaluru’s data shows that its arterial roads are most dangerous for pedestrians. In 2017, the city’s arterial roads alone claimed 186 pedestrians. That is, 65 percent of the total pedestrian deaths that year occurred on these roads, which make up less than 10 percent of Bengaluru’s total road length.

And 2017 may not be an aberration – preliminary data for 2018 hints at a similar trend. The city seemingly has no plan to deal with this urgent matter.

Pedestrian victims in 2017, as recorded in FIRs

| Number of crashes that killed pedestrians | 276 |

| Total pedestrian deaths | 282 |

| Number of pedestrian deaths on arterial roads alone | 186 |

| Number of pedestrians injured in crashes | 1332 |

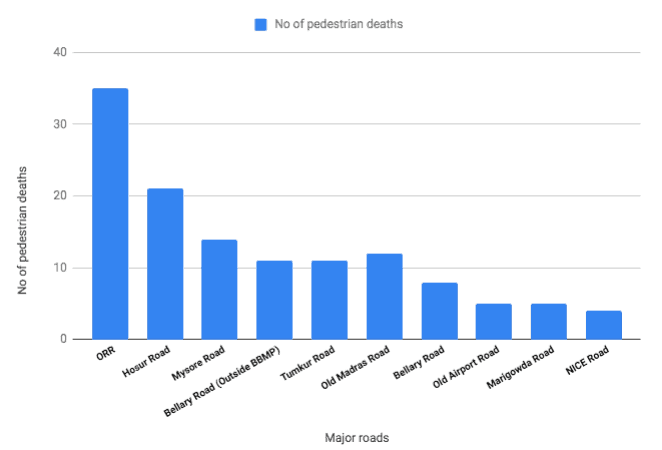

Pedestrian deaths highest on Outer Ring Road

Bengaluru has 80 arterial roads, covering a total distance of around 923 km. These high-capacity roads, typically as wide as 50 meters, are designed to move vehicles with minimal obstruction. What the design discounts though, is pedestrians’ need to use these roads.

Arterial roads which, at the core, are designed to allow unobstructed movement of vehicles at high speeds, are principally incompatible with the designs needed to make roads safer for pedestrians. And, time after time, we have prioritised free movement of vehicles over the safety of pedestrians. This costs us hundreds of lives every year, in Bengaluru, and in other cities across the country.

Bengaluru’s Outer Ring Road is especially notorious. Twelve percent of all pedestrian deaths in 2017 occurred on this road, which is about 80 km long, as per FIR data we obtained through an RTI application. Nearly all these crashes happened while pedestrians were crossing the road.

| Major roads | No. of crashes that killed pedestrians | Percentage of fatal crashes (as % of such crashes in city overall) | No. of pedestrian deaths | Percentage of pedestrian deaths |

| ORR | 33 | 12% | 35 | 12% |

| Hosur Road | 21 | 8% | 21 | 7% |

| Mysore Road | 14 | 5% | 14 | 5% |

| Old Madras Road | 10 | 4% | 12 | 4% |

Hosur Road, Mysore Road, Bellary Road, Tumkur Road, and Old Madras Road were other major arterial roads where pedestrian crashes were rampant.

Why are arterial roads more dangerous?

Pedestrians crashes were especially severe in the arterial stretches in peripheral areas of the city. This is probably because some of these stretches are signal-free, causing vehicle speeds to be comparatively higher than in the central areas of the city. This could also be because most roads in the peripheries do not have pedestrian facilities.

Take the example of a 10-km stretch on Hosur road between Silk Board Junction and Electronic City, which recorded over 20 pedestrian deaths in 2017. Pedestrians have no walkable footpaths on this stretch, neither do they have adequate pedestrian signals or midblock crossings (a crossing between two consecutive intersections) to safely cross the road. Contact with high-speed traffic, therefore, was always inevitable.

Most victims were from low-income households

Analysis of the FIR data also revealed that a majority of victims who were killed on the arterial roads resided in areas adjoining these roads. Daily access to these roads is crucial for them to go about their lives. We also learned that most victims hailed from low-income households. Crashes, therefore, can also significantly impact the livelihoods of the affected families.

Rather than addressing such issues and making roads safer for pedestrians, our cities may very well be discouraging pedestrians from using these roads. Most arterial roads have blocked medians without any provision for crossings, whereas the IRC recommends at least one safe crossing every 250 metres. Indian Road Congress (IRC) is a technical apex body that issues guidelines for the design and construction of roads.

Vehicles often crowd pedestrian crossings, endangering pedestrians. Pic: The Footpath Initiative

In the absence of safer means to cross the road, pedestrians are effectively forced to cross dangerously. Of the 186 people who lost their lives along arterial roads in 2017, 125 had been attempting to cross the road. (Others were killed while walking along the road, or while doing an activity or waiting for a bus on the roadside.)

Skywalks mushroom, but hardly help

Earlier this year, BBMP had proposed construction of 52 skywalks in the city. Can such infrastructure prevent pedestrian deaths?

Skywalks and foot-over-bridges, which are usually sparse, are shunned even by able-bodied pedestrians as these increase walking distance and time, making road crossing highly inconvenient. How can such exclusionary infrastructure serve the needs of the elderly, for example, who comprise nearly a third of all pedestrian crash victims in the city?

The cost of prioritising vehicle speed over pedestrian safety is not limited to deaths and injuries. It can have far-reaching consequences on the mobility and quality of life in cities. At least half of Bengaluru’s population either walk, or use public transport which in turn is accessed by walking.

The lack of safe walking spaces can discourage the usage of public transport while increasing the reliance on private modes. This would worsen traffic congestion and air pollution. Increasing reliance on private transport can also generate a demand to increase the road space to accommodate these, at the expense of shrinking pedestrian spaces further.

What’s the solution?

A proactive approach of designing our cities with pedestrians at the centre, has the potential to break this vicious cycle. As a bare minimum, we have to work towards providing:

- Footpaths of at least 1.8 m width on all arterial roads

- Signalised intersections with safe design and adequate pedestrian crossing time

- Midblock crossings at the needed frequency, with traffic calming measures to enable speed control

Every day that we spend considering plans to widen roads and build signal-free corridors, which blatantly exclude pedestrians, we are taking a step back. Every skywalk and foot-over-bridge that we build haphazardly, assuming that these are adequate to serve the needs of pedestrians, are putting more and more pedestrians at risk.

[Varun Sridhar also contributed to this article]