In August 2019, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike had invited citizen groups and other organisations in Bengaluru to adopt streets. Under this volunteer initiative, the adopter has to maintain streets and ensure their visual cleanliness. Nearly one-and-half years later, the project is yet to kick off.

D Randeep, Special Commissioner (Solid Waste Management) at BBMP, says the delay was due to COVID and that the programme would likely be resumed in the first week of February. “During COVID, we did not want people to come out together and do community work, which would be required under AASI. Before COVID, we had meetings, and the paperwork was done from our end. Over 20 adopters were willing to adopt roads.”

The final draft of the MoU was sent to prospective adopters in mid-March, just before the COVID lockdown. “Since March 20, there has been no communication from BBMP or The Ugly Indian,” says Amit Kumar, President of SwarnaBegur Welfare Association for Residents (SWAR).

The Ugly Indian (TUI), a citizen movement for clean streets, is partnering with BBMP for the initiative, and had in fact mooted the idea of AASI. India Rising Trust, the NGO that supports TUI, is the official partner in the records.

Amit Kumar says that SWAR had proposed adopting a stretch of 2.5-3 km on Begur Main Road, from Begur village to St Mary’s School circle. “Begur is a new settlement with upcoming apartments, close to Electronic City. It does not have as much infrastructure and facilities as core areas. We decided to adopt the street as the government would only take things up on priority basis.”

23 prospective adopters

According to the list TUI and BBMP shared with this reporter, 23 organisations were ready to adopt a total of 53 streets as of last March. Nearly half of these were corporates, including big names such as Prestige and Embassy, and several smaller ones. Others in the list include NGOs, RWAs (Resident Welfare Associations) and educational institutions.

The roads planned for adoption are spread across Bengaluru, but mostly concentrated in the centre, east and south of the city. They are located close to the homes, offices or project locations of the adopters, revealed a co-ordinator at TUI and India Rising Trust.

The draft MoU prepared by the BBMP says that the civic body retains the primary responsibility to maintain infrastructure and services on the adopted road, and the adopters’ services would be in addition to these. The adopter should deploy staff for supplementary litter-picking and other activities at their own cost. Their staff shall carry identity cards as well as a badge on their uniforms. If the adopter wants to invest in large infrastructural works on the road, they need to enter into a supplementary agreement with BBMP, says the MoU.

The MoU would be for a year, and the adopter should submit monthly or quarterly reports of their work to the BBMP for review. Either party can cancel the MoU by giving prior notice of 30 days.

Scope of activities under the MoU:

- Augmenting BBMP efforts for street cleaning through

- clean-up drives at least once a month

- providing own staff for litter-picking support

- eliminating garbage-vulnerable points

- reporting illegal dumping of mixed waste, lack of visual cleanliness caused by incomplete works or materials left on road by government agencies

- reporting, and where feasible, removing illegal banners, posters, etc

- Street greening

- supporting maintenance of trees on footpaths

- planting new trees as per approval, reporting trees that need trimming

- reporting and removing posters that deface trees

- Street walkability:

- executing minor repairs to damaged footpaths

- help remove minor obstructions on footpath

- help prevent water-logging and facilitate water flow into stormwater drain

- reporting non-functional streetlights

- Adding street furniture like benches and dustbins with prior approval (optional)

Pilot on 10 CBD streets

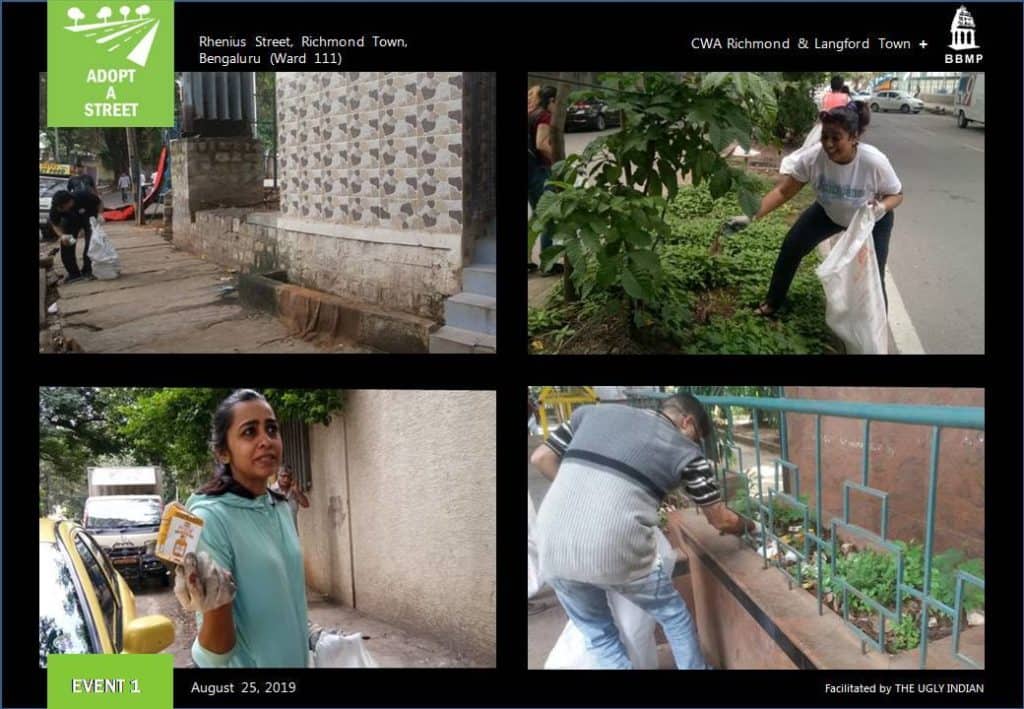

Soon after AASI was announced, India Rising Trust signed an MoU with BBMP to do a pilot in 10 TenderSURE roads of CBD (Central Business District).

These were: Church Street – 0. 8 km; Lavelle Road – 1.5 km; St. Mark’s Road – 1 km; Residency Road – 1 km; Museum Road – 0.8 km; Magrath Road – 0.8 km; Richmond Road – 2.75 km; Commissariat Road – 0.4 km; MG Road – 2.25 km and Brigade Road – 0.8 km

The TUI co-ordinator says, “The India Rising Trust adopted these roads to demonstrate to the adopters what could be done under the initiative.” TUI made an example out of Church Street, especially, on social media.

“We ensured the dustbins on the street were well-maintained, and had personnel to ensure there was no littering. Over time, vendors on the street took initiative to prevent littering. This example shows that if you keep a street clean, and people see that it’s consistently managed so as to be kept clean, they too will follow it,” he says.

TUI sends out two people to check Church Street every morning, and puts up the video on social media. “There has been zero litter in the street for weeks,” he says.

“Adopt according to ability”

TUI and BBMP have said that adoption of streets is a common practice across the globe. Yet questions have been raised as to whether BBMP is burdening citizens further with this initiative while many of the city’s streets lack basic infrastructure.

The TUI co-ordinator says, “This is not a contract. AASI is only a voluntary initiative and there is no financial transaction involved. So BBMP cannot mandate the adopter to take up specific activities. The MoU only mentions broad terms.” He says the adopter has to give the basic commitment of having clean-up drives and keeping the street litter-free; other activities are optional.

Asked whether funds or manpower would be an issue in street adoption, Amit Kumar of SWAR says, “We can raise funds from corporates or individuals; that’s how we raised funds for all events of SWAR in the past four years. But since the MoU was not signed, we couldn’t ask for funds yet,” says Kumar.

But Rajendra Babu of Koramangala ST Bed Layout RWA says mobilising funds wouldn’t be as easy for them. “We are unable to collect CSR funds and can only use funds collected from the community over time.”

The TUI co-ordinator says adopters can be smaller groups too, and can do whatever they can to make their streets better, even at little expense. “For example, much of the littering of streets happens in the afternoons. If there are two restaurants along the street, the adopter can simply employ a person to go around in the afternoon to pick up any waste lying around.

It may cost, say around Rs 3,000 to pay the person per month. Even individuals can spend this amount. This would also be a way to employ people who have lost jobs during COVID.”

He says applicants were not asked to give details of funds or manpower during the selection process.

“We had email exchanges with the applicants to find out if they had prior experience such as spot-fixing or waste management, what part of the street they wanted to work on, what were the specific issues they identified there and what solutions they had, etc. With this, we could tell which applicants were genuine,” says the coordinator.

He points out that adoption of streets, parks, etc was possible even before AASI; citizens only had to send an application to BBMP and get its approval. With AASI, it is being formalised. Whether citizens can invest in public streets is a grey area legally, so a formal programme would allow them to participate, he says.

“Also, multiple agencies like BBMP, BESCOM, Horticulture and Forest departments are involved with streets, but there is no single agency that’s responsible for a street. With AASI, local citizens can ensure everything works in their street.”

He says that even without the AASI MoU, some applicants are already doing work, such as the Embassy Group that recently painted the pillars along the Hebbal-airport stretch.

[With inputs from Harsha Raj Gatty]