Bengaluru, the Silicon Valley of India, is home to a number of technology parks. Amongst the largest is Brookfield Ecoworld, located in Bellandur where employees from across the city work. Adarsh Palm Retreat (APR), meanwhile, is a fancy apartment and villa complex located adjacent to this tech park’s entrance.

APR and Ecoworld are typical examples of the nexus that developed between office/commercial complexes and upscale housing for white collar workers during the Information Technology (IT) revolution in the city. It addressed a definite need among select sections of the population, but a closer look reveals the clear divide and inequities that such development created and sharpened.

Based on our interviews and data collection, APR’s residents consist primarily of employees working in the technology sector. Many therefore enjoy the benefits of being situated right in the middle of the IT corridor, avoiding traffic congestion on their way to work and also contributing minimally to it. Some are employees at Ecoworld itself, who proudly tell us how they can simply walk to work.

‘Ecoworld’ and ‘APR’ share an intimacy, facilitated largely by private roads connecting the High-Tech Industrial Zone and the high-end gated community. Together, they produce an enclave that uses ring fencing, car-oriented accessibility and other socioeconomic means that effectively filters out the lower class.

Read more: 2 km drive takes more than an hour – why Bellandur citizens are protesting

Steps away, worlds apart

In July, 2024 we took a 6-km walk in and around the APR-Ecoworld Campus, and observed the sheer contrast in the everyday experiences of those within and those outside the walled enclave.

In a walk through the campus, one sees clear, wide boulevards lined by neatly trimmed hedges that direct you to expanses of glass in office buildings and commercial spaces. In this quiet and comfortable bubble away from the city’s hustle, the environment is seen as ‘conducive for families’ by many of the people we spoke to.

The wide array of facilities available in APR — such as sport terrains and green spaces — appeal to people in all age groups.

Mornings see a number of international school buses picking up children before their parents go to the office. And then in the evenings, a common sight is groups of elderly women chatting under gazebos, while children play football and adults walk with their partners.

For the entire stretch leading up to the apartments and villas, tall glass buildings that house multinational companies (MNCs) and high-end commercial spaces have been built, intended for the formal office workers of Ecoworld and affluent residents of APR (who frequently overlap). The stores are swankily decorated, with interiors that resemble their counterparts in the west.

Bottom left: The tall walls and barbed wires of APR-Ecoworld (bottom left).

Right: In the cramped alleyway between APR and a store, shanty housing has developed (right). Pic: Abhay Chetan Narasimhan.

These clean and well-lit roads within the enclave stand in stark contrast to the parallel alleyway right outside APR’s walls, wherein shanty housing has developed. The barbed wire extends beyond the verticality of the wall, so residents of the cramped alleyway often use it to hang their clothes up to dry.

The APR ‘backgate’ is reserved exclusively for residents of the villa complex and its associated service workers. This gate not only offers a more direct entry for APR villa residents, but also a less-visible side entrance for service workers to go through. The first image above shows a service truck being checked for permissions at the gate, while a staff member is walking to their workspace.

Selective connectivity

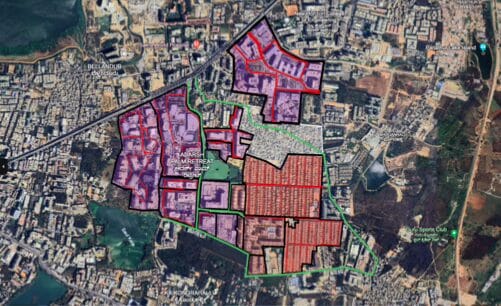

Devarabeesanahalli is the modernised village that APR-Ecoworld is registered under. The image above shows private roads and public roads linked to one another, beneficial if you’re an APR resident. Otherwise, the gated community of APR-Ecoworld is inaccessible for other village residents and daily-wage labourers in the area.

The private road shared by APR and Ecoworld, initially open to the public, was closed off to wider use due to protests by APR residents. Now, the bulk of vehicular traffic occurs through its single main road – one of the most traffic-heavy sections in the world’s sixth most congested city.

Additionally, Devarabeesanahalli Lake, a supposed-public space, has been cordoned off by the APR-Ecoworld campus. To visit the lake from the village, villagers now have to take an uncomfortable walk through a busy and dusty Outer Ring Road.

The closest bus stop to APR’s apartments is a 2.1 kilometre walk. Domestic help and maintenance staff members often come from distant parts of the city. APR doesn’t offer any shuttles from the bus stop for service workers, or even inside the enclave.

2. Aerial view of the informally planned metal-shed roofed concrete housing, less than 20 metres away from APR-Ecoworld’s walls in Devarabeesanahalli. Pic: Abhay Chetan Narasimhan.

Exclusion of essential workers

APR-Ecoworld is growing, Bengaluru’s civic corporations continue to approve more apartment complexes, more villas, more offices within the campus. Hardly a day goes by when APR-Ecoworld isn’t dug up. In order to sustain the constant expansions and to service the campus, hundreds from the unorganised sector work on the site.

From our conversations with these individuals, we got the sense that APR-Ecoworld’s design and practice contribute to the feeling of unwelcomeness. Many cleaners cited not receiving any drinking water supply from Adarsh, relying on help from the residents to receive access to these basic services.

Peeping into the muddy APR Mayberry construction zone, one can see worker-housing (temporary) characterised by cramped ramshackle metal huts with few common spaces. Interviews with such workers reveal that Adarsh and Brookfield builders employ these workers on informal and low-paying contracts. Basic services such as housing, electricity and water are provided at infrequent intervals.

A history of exclusionary urban development

This painted poster of the ‘Dalit Sangrahalaya Samiti’ (DSS) on the corner of the APR exterior wall represents a protest against the land-acquisition methods and hierarchies of APR, often taken to local courts.

Bellandur, just 25 years prior, was predominantly agrarian in its land use. Researchers Lalitha Kamath, Vinay Baindur and P. Rajan explain in their paper “Urban local government, infrastructure planning and the urban poor” (p. 29) how the Gram Panchayat recognised the Reddy community as owning 50% of the land while the Thigala and Dalit communities were farmers and worked as daily-wage labourers in Bellandur.

From a conversation with Dr Vivek, environmental researcher and resident of APR, we learnt how farmers and daily-wage labourers had ‘secondary rights’ to the land. The Reddy community would allow Dalit citizens to work through informal, verbal contracts. However, as Bellandur rapidly adopted tech-based development and land records were digitised, such informal agreements were abandoned.

Consequently, local landowners and the landless suffered as unelected parastatal bodies such as Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) and Karnataka Industrial Area Development Board (KIADB) acted as aggregating intermediaries, selling land to private developers like Adarsh.

Lalitha Kamath and co-authors further reveal how large real estate companies brokered with local elites and wealthier landowners to obtain the territory, circumventing direct negotiations with lower-paid locals i.e. Dalit and Thigala communities.

Recent news tells us that Bengaluru will be home to 89 more tech-parks across areas such as Bellandur and Whitefield. Invariably, more tech-adjacent townships will develop across the city, that will continue to promote the kind of intimacy between technology and housing that we see here. However, in view of what the APR-Ecoworld ecosystem showcases, caution is necessary when supporting the development of such spaces — to safeguard against the spatial inequalities they continue to develop and sustain.

Excellent, well written article. As I finished reading the article, I noticed that the authors of the article are actually college students, and that left me thoroughly impressed.

They have articulated the issues of gross disparities, life in a bubble, and exclusionary Development of Bangalore extremely well.

Very well written article. Good Job.

👍

Encouraging students to approach life with positivity is essential. Articles like the one on Bengaluru’s APR-Ecoworld highlight genuine concerns about urban development and inequities but often focus on problems. It’s important for students to critically engage with such topics, balancing critique with optimism. They should recognize progress, consider collaborative solutions, and learn how diverse perspectives can drive innovation. By adopting a solution-oriented mindset, they can contribute meaningfully to societal challenges, seeing opportunities for improvement rather than being weighed down by negativity.