Debashish Mondal looked vacantly at the broken walls of his home. All that remained of the house he was born in 35 years ago was broken bricks, chunks of cement and a shattered roof.

On November 11, the colony he lived in, under Tallah bridge in north Kolkata, home to around 60 families, was reduced to rubble. The local municipal authorities and personnel from the Public Works Department (PWD), along with a posse of cops, came around 10:30 that morning. They had brought along labourers for the demolition, and two days later also called in bulldozers for some of the cement structures. It took around a week to obliterate the basti. Two half-demolished houses are still standing, while the daily wage labourers continue (in December) to level the ground, clearing the debris.

Tallah bridge is located on BT Road’s Nazrul Pally lane. The basti’s inhabitants estimate that their colony – built on land that belongs to the PWD – was more than 70 years old.

“It was [like] a bolt of lightning!” says Debashish, an ambulance driver who earns Rs. 9,000 a month. He had borrowed around Rs. 1.5 lakh from local moneylenders and friends to build a pucca house in place of the thatched shelter where his father was born. His grandparents had come to Kolkata several decades ago from Daudpur village in Sandeshkhali II block of North 24 Parganas district – part of the Sundarbans – in search of work.

The house Debashish built has been demolished. Much of his high-interest loan remains.

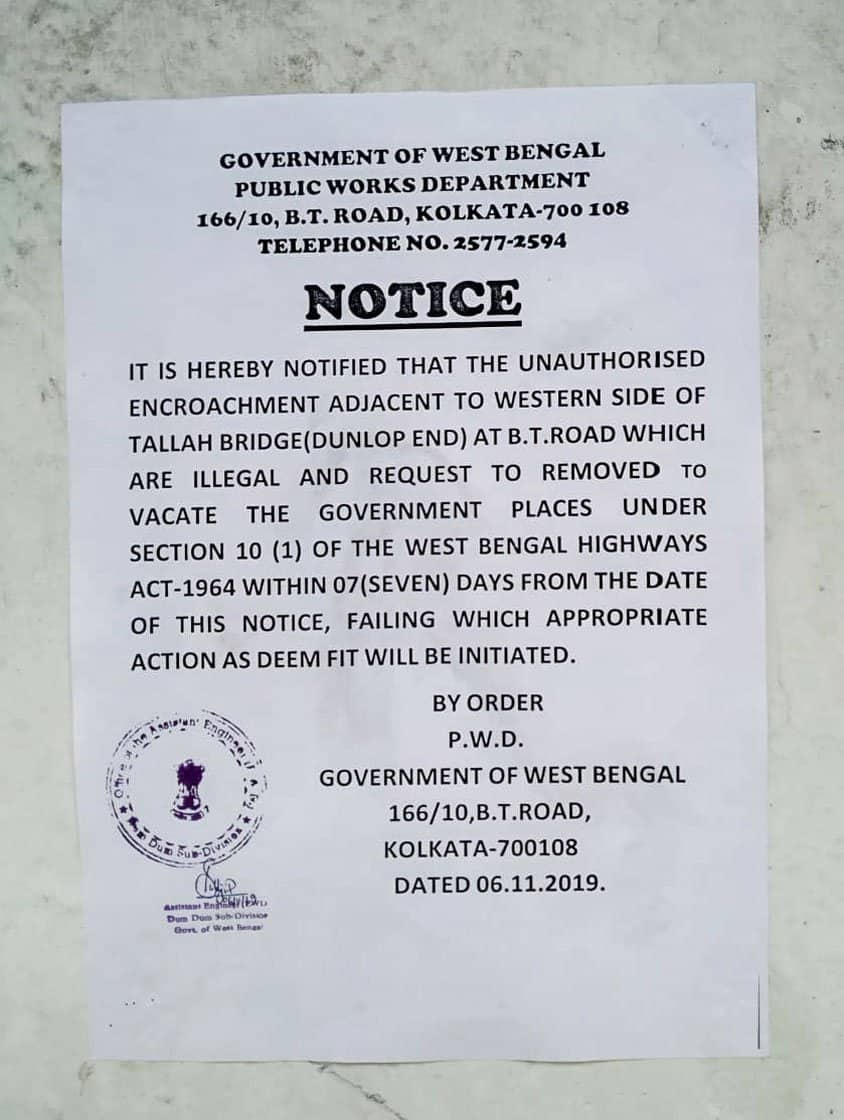

Trouble began for the residents of the Tallah colony on September 24, when the PWD and municipal corporation authorities informed them verbally that the bridge had to be repaired. They would have to leave with a few belongings, and could return when the repairs were complete. On the evening of September 25, the 60 families were moved to two nearby transit camps – one on railway land, the other near a canal on land owned by the state irrigation department.

Reduced to rubble: the demolished Tallah bridge basti and Debashish Mondal (top right) at the broken house he had saved and borrowed to build. Pic: Smita Khator/ People’s Archive of Rural India

Around 10 other families remain in an extension of the Tallah basti, on the opposite side the narrow road, awaiting relocation. Among these 10 families is Parul Karan’s. She is a former domestic worker, now around 70 years old. She points to the bridge and says, “This was originally made of wood. Many years ago a double-decker bus fell from there. When the wooden bridge was converted to concrete, nobody was evicted.” Parul is a widow and a diabetic; her daughter supports her with her income as a domestic worker.

Karan’s family too came to Kolkata around 50 years ago, she recalls, from Daudpur village. “It was not easy to survive in the mud and water among snakes and frogs in the Sundarbans. When we came from the village, this place was full of shrubs and weeds, frequented by goondas and bodmash,” she says. “We had to return home by afternoon right after work at the babu’s place.”

The transit camps that Parul’s neighbours have moved to are long bamboo structures covered with black tarpaulin sheets, erected by the municipal corporation. Each structure is divided into rooms of 100 square feet each. Electricity is available only from 5 p.m. to 5 a.m. During the day, due to the black tarpaulin, it is dark inside the rooms. The camp in the railway yard is in a low-lying area that got flooded during a cyclonic storm, Bulbul, on November 9.

“The day the storm came, this place got completely water-logged,” says 10-year-old Shreya Mondal, who studies in Class 5 in a nearby government school. She and a few children of the basti were playing in the field adjacent to the railway yard when I visited the camp. “There was knee-deep water in our rooms. With much difficulty, we could save our books. We had lost so many of our toys, skipping ropes and dolls during the demolition…”

Top left: Parul Karan, Parul Mondal (centre) and her sister-in-law say they settled under the bridge over 50 years ago. Top right: Karan and her daughter, who have not yet shifted, show their electricity bill, hoping to prove that they are legitimate residents. Bottom row: The ‘transit camps’ at the railway yard (left) and near the Chitpur canal (right) Pic: Smita Khator/ People’s Archive of Rural India

People in both the camps continue to use the toilet block (still standing) that they had built at the bridge basti. The residents of the transit camp near the canal – located further from Tallah bridge than the railway yard camp, are compelled to use a public pay and use toilet, which closes by 8 p.m. Thereafter, they have to walk to the toilet in the demolished basti area – and the women complain it is unsafe to do that at night.

Near the canal, I met 32-year-old Neelam Mehta. Her husband, who came to Kolkata from a village in Jamui district of Bihar, is a street vendor selling sattu (gram flour). Neelam is a domestic worker. “Where will we go?” she asks. “We are surviving somehow. We have been here for many years. I want my daughter to have a better future. I don’t want her to work at people’s homes. My son is also studying. Tell me, how can we survive in this situation?”

She says they have been promised that a toilet will be built near the canal camp. Till then, she and many others have to spend Rs. 2 for every visit to the public toilet. “How can we afford to pay for toilets? Where will women and young girls go at night? Who will take the responsibility if something happens?” she asks

Her 15-year-old daughter, Neha, is studying right beside her mother, sitting on the floor of their transit camp room. “It’s very difficult to study like this,” she says. “There is no electricity during the entire day. How will we complete our studies?”

Where will we go?’ asks Neelam Mehta, while her daughter Neha struggles to study. Pic: Smita Khator/ People’s Archive of Rural India

Dhiren Mondal asks, ‘Tell me, where should we go?’ Pic: Smita Khator/ People’s Archive of Rural India

On the way to the shelter is a Goddess Durga temple. The evening prayers here are offered by 80-year-old Dhiren Mondal, who is now staying in a room in the railway yard transit camp. “I have lived here for more than 50 years,” he says. “I am from the Sandeshkhali region of the Sundarbans. We had to leave everything to find work here. Our village had been swallowed by the river.” Pulling loaded handcarts by the day, Mondal raised three children in a house made of bamboo in the Tallah basti, which the family eventually converted into a concrete structure.

“The [municipal] councillor asked if we had taken his permission to build our homes!” he says. I told him that we have been staying here for the over 50 years, how could he ask us to leave all this without a proper alternative? How could he evict people like this? Tell me, where should we go?”

When the cops came on the evening of September 25 and asked the residents to start moving, alleges 22-year-old Tumpa Mondal, “They began bad-mouthing my mother-in-law, they pulled my brother-in-law by his collar to the camp. When I went to stop them, I was pushed and shoved. I am pregnant, but they did not care. They pulled women by their hair. There was not a single female cop. They were using abusive language.”

(However, in an interview with this reporter, the officer in charge, Ayan Goswami, of the Chitpur police station, around 2.5 kilometres from the Tallah basti, denied any rough handling or coercion. He said he was sympathetic about the families, but eviction was unavoidable because the bridge had been declared dangerous by qualified architects. The basti dwellers, he said, would have been the first casualties of any portion of the bridge collapsing.)

Sulekha Mondal cooking lunch under a shade in the demolished Tallah colony. Top right: ‘Poor people have always stayed on sarkari land, otherwise where will we stay?’ asks Lakhhi Das. Bottom row: Women at the transit camps are finding it especially hard to walk long distances to their old basti’s toilet block. Pic: Smita Khator/ People’s Archive of Rural India

The local councillor, Tarun Saha, of the Trinamool Congress, told me on the phone, “They are encroachers. They have no legal right to stay there. They used to live in shanties. We provided water and sanitation on humanitarian grounds [for the Tallah basti]. Eventually, they converted the shanties to pucca houses.” The bridge, he adds, is in a dangerous condition. “It needs urgent reconstruction. There could be casualties if not repaired. They had to be moved.”

The government, Saha says, is yet to decide about the permanent rehabilitation of the Tallah families. “As of now, we are letting them stay in the temporary shelters. In future there might be arrangements to cover the shelters with tin roofs. But we will not allow any concrete structure,” he says. “They have houses elsewhere,” he adds, referring to their villages and, in some instances, land some families have managed to purchase in fringe areas. “They have encroached on this place for the sake of their work. They have been here for a very long time. They kept on bringing their families. Many of them are well off now.”

“Poor people have always stayed on sarkari land, otherwise where will we stay?” asks Lakhhi Das, 23, a homemaker, whose husband works as an office assistant. Along with their two daughters, they too were shunted out from the Tallah basti . “We are poor. We earn with our labour,” Lakhhi adds. “I am facing all the difficulties only for my daughters.”

The demolished basti’s residents want a written assurance from the councillor that after the bridge is repaired, they will be allowed to return. No such assurance has been given so far.

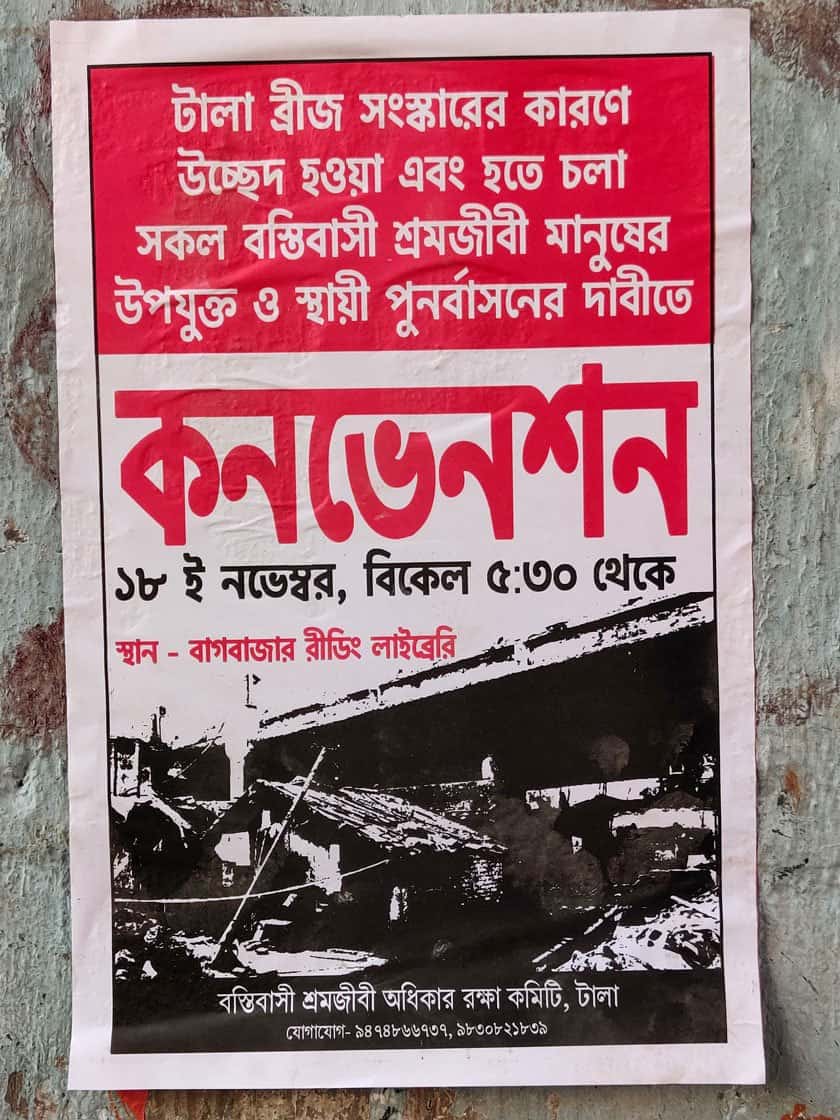

A poster calling for a meeting on November 18 to demand proper and permanent rehabilitation of evicted families. Pic: Smita Khator/ People’s Archive of Rural India

The Tallah basti residents at a protest march on November 11. Pic: Soumya/ People’s Archive of Rural India

There have been small acts of resistance – on September 25, when they had to leave their homes, the Tallah colony residents blocked the bridge for around an hour at 10 p.m. On November 11, they took out a morcha. On November 18, they held a public meeting to voice their demands. Coming together as the Basteevasi Shramjivi Adhikar Raksha Committee, they are lobbying for toilets and regular electricity, and planning to build a community kitchen that would bring down costs for each family.

On November 25, Raja Hazra, a street vendor, whose family was also evicted, filed a petition in the Kolkata High Court on behalf of the evicted slum families. Their main demand is proper rehabilitation – a permanent place to live from where they won’t be evicted, not too far from their demolished basti (which was close to their workplaces and schools), and basic services like electricity, water and sanitation.

Back in the transit camp, Sulekha Mondal has lit a mud oven. It is 2:30 in the afternoon, she has just returned from work at the nearby houses – she will go back to those houses to work again in the evening. Stirring brinjal, potatoes and cauliflower in the pan, she says, “The councillor told us to go back to the village! Four generations ago, we left Daudpur. Now we are being told to return? Everyone knows the conditions in the Sundarbans. Whatever little people had got devastated during [cyclone] Aila. We are not hurting anybody. We also want the bridge to be repaired. But the government must rehabilitate us.”

The reporter would like to thank Soumya, Raya and Aurko for their help.

(This article was originally published in the People’s Archive of Rural India on December 12, 2019)