In recent years, we have seen a dramatic rise in instances of flooding, along with increasing population density and expanding concrete surfaces. All these add extra pressure to the stormwater drain networks, which also put people living near drains at risk. Therefore, the question that arises is do we need to revisit engineering designs of stormwater drains?

Pipes and sewage drains, symbolic of the colonial period, displaced the traditional systems of water from wells and lakes. This is because piped water, which brings water into the city, and drains, carrying sewage out, were viewed as indicators of modernity. The problem that arose in this system is the combined sewer and stormwater drains, something that our cities continue to battle.

In the book, In the City, Out of Place, by Awadhendra Sharan, on the contemporary history of environmental issues in Delhi, this reference from the chapter Continimated Flows, aptly describes the problem. J Robertson, Sanitary Commission Government of India, on the Delhi drains, noted his observations in the late 1800s, on the making of the new capital city, “Within the city walls, all storm water and sullage continued to be carried out by a system of surface drains and underground sewers to the city ditch…Silt should be removed from the city ditch so as to give a freer flow to the sewage, the rubbish cleared”.

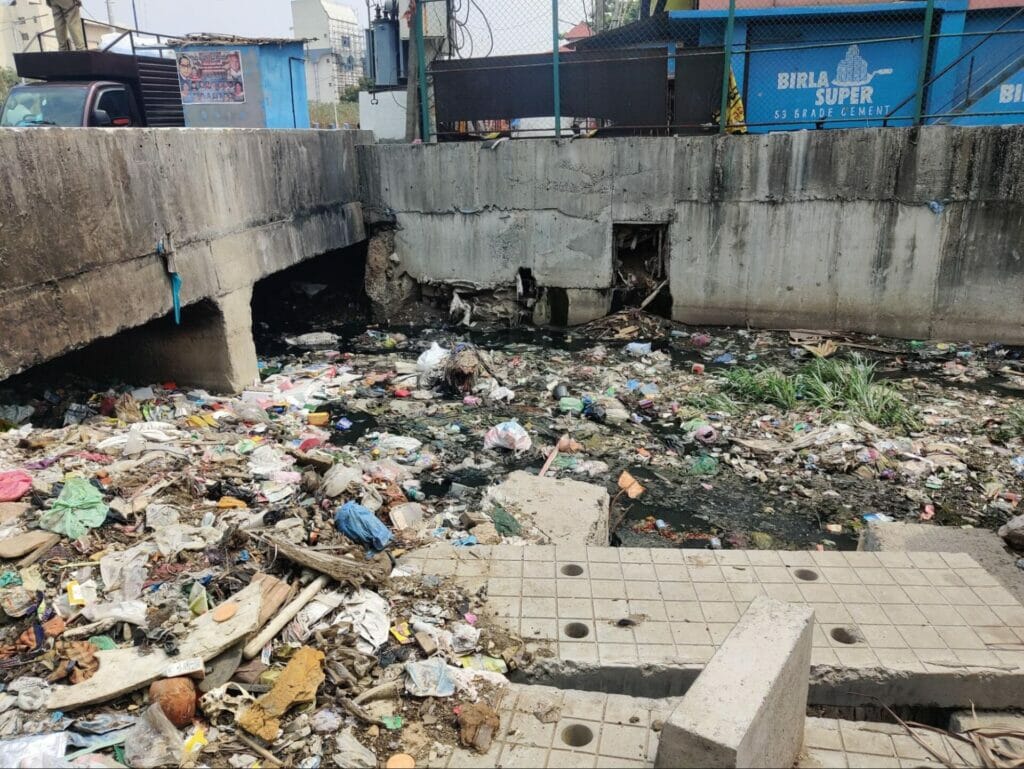

But is this all to it? Professor HS Sudhira points out that natural streams have been engineered into stormwater drains, as many of the original streams have been covered or altered, and some have actually disappeared or are untraceable. Do you then refocus our attention to design? Constructing or designing better stormwater drains, will need diverse elements of policy making, engineering, community participation, innovation, education and a reconfiguration of our view of our natural topography.

Drains’ relationship with communities

Stormwater drains have often been viewed in a conventional approach that is purely hydrological or technological. However, this flawed approach to stormwater management fails to take into account the ability of these drains to transform or disrupt communities, often leaving them with hydro-social scars.

The important aspect of reimagining stormwater drains is the negotiations of everydayness – from water, power, waste, transport, and governance. As seen in the recent floods of 2022, inequalities get perpetuated. Sumanto Mondal has traced the caste lines in Bengaluru, on Google Earth, showing how the city’s plateaus/highest grounds are monopolised by the most elite residential areas, while the lowlands that aid a natural drainage from affluent areas have been used by successive administrations to settle lower caste populations.

“Many of the migrant workers who were dispossessed by the flooding are from northern and northeast India, it is only a matter of time before some politician starts to call them encroachers”, says Malini Ranganathan, Associate Professor, School of International Service, American University, who has spent over a decade researching the city’s wetlands, real estate, and informal urbanisation.

History has shown that often after floods, we react with an urgency, blaming and accusing but then, as time passes, we forget. And then use public money to compensate for administrative inefficiency.

Read more: A historical lens on Bengaluru’s drains

The questions to ask are also: how did these areas come to be? How was the land allotted? Why were there no proper facilities available? Malini’s study also makes an important observation and she states that how the city was developed and states: “Much of Bangalore’s land has been ‘informally’ developed, both by higher-end and lowerend settlers, yet it is the lower-end settlers who are denied state-provided infrastructure since they are deemed illegitimate”.

“For people living near drains, they (the canals) serve no utilitarian or recreational purpose. If you look at older maps of the city, you will notice that drains are an integral part of the city. In the rapid urbanisation of the last few decades, these drains, their valleys and catchments have been largely ignored in the larger planning of the city. It’s only in recent years that there has been attention around these drains, mainly as feeders to the tanks,” says Amritha Ganapathy, Architect and Urban Designer. And the attention to this spikes when there are floods.

The Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (URDPFI) guidelines recommend that cities have 10‐12 sq.m open space per person. “According to the WRI India 2020 blog, Bengaluru offers only 2 sq.m of open space per person. “Imagining the stormwater drain as part of the city’s architecture is crucial. We need to reclaim these waterways as open spaces that can improve the health and wellbeing of the citizens”, says Amritha. It is beyond just a critique of what exists today, but the thrust must be for what it should be.

More than beautification

“Stormwater drains are important connectors of the water ecosystems in any city. Threats to these lifelines or connectors can have serious repercussions, like we have recently witnessed with the August-September (2022) rains, in Bengaluru“, says Srinivasulu, IFS, Member Secretary, Karnataka Pollution Control Board. “In this context, K100 is an important pilot project that aims to showcase a three point agenda: reestablish canals as an essential multifunctional part of our green infrastructure for our water ecosystems, prevent pollution, and create a public space, and that needs a paradigm change in our imagination”.

However, the K100 Citizen Water Way project might not be enough. Can we then take a leaf out of China’s ‘sponge cities’, which involves banning new developments on flood plains and wetlands, or Tokyo that has large underground water reservoirs and separate sewage systems or Singapore’s National Water Agency – the Public Utilities Board (PUB) of developing water canals across residential areas?

Read more: Lack of stormwater drain planning in Bengaluru is a risk factor for future floods

“We need to transition to a model of water sensitive cities like Australia”, says Myriam Shankar, founder of the Anonymous Indian Charitable Trust (TAICT). In water sensitive cities, water plays a central role in shaping a city. So from reliable water supply, to sanitation provisions, to green landscapes and healthy ecosystems that also prevent flooding, this would mean integrating infrastructure, design and governance together in a system. And this would also help create community guardians and empowered communities.”

The fact of the matter remains that we need collective imagination to expand possibilities that are diverse, equitable, gendered, and sustainable. Mere beautification, without fixing the root cause of the problems, would just remain an isolated capital intensive exercise. We have to remember that water, in the end, has retentive memory and communicative abilities.

The recent floods stand as a testimony to our inadequacies as what Henri Lefebvre points out in his Critique of Everyday Life, “ the desire to seek aesthetic refuge from the disappointments and horrors of the everyday”, compounds the problems and negates the possibilities of imagination.

Need for equitable urban service provisions

The government will also need to keep up with urban service provisions, such as streamlined waste management systems, regular drainage and lakes cleaning, inclusive land planning.

The World Resources Institute recommends for cross sector approaches moving away from siloed-sector approaches and lists some key points a) Municipal infrastructure must be designed and delivered to prioritise neglected populations, including addressing backlogs to basic services; b) Integrate and strengthen alternate partnerships, for example water supply, transport etc; c) Improve data collection through community engagement, as the need for granular local data on vulnerability cannot be underscored; d) Transparent and well regulated land development and upgradation of existing informal settlements; e) Creating coalitions of diverse actors.

Reconnecting people with stormwater drains

Another key component on reimagining stormwater drains is the need for landscape literacy. In the chapter, Restoring Water by Anne Whiston Spirn, in the book Design In The Terrain of Water by Anuradha Mathur and Dilip Da Cunha, the author describes ‘landscape literacy’ as a cultural practice that entails both understanding the world and transforming it. Anne says: “Landscape illiteracy is an environmental injustice, and an even greater injustice than inequitable exposure to harsh conditions… because of the internalisation of shame in one’s neighbourhood.”

So, in order to reconnect people with water, local communities need to be landscape literate, develop an understanding of the stormwater drains, and the larger ecosystem, and how it works within their locality; build an appreciation of challenges; and be an active participant in the process of addressing those challenges. After all, as the West Philadelphia Landscape Project states: Water is an issue that holds great promise for combining environment restoration and community development.

Jane Jacobs in her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, states: “Please look closely at real cities, while you are looking you might also listen, linger and think closely about what you see”. So the question is, how do we see storm water drains?

This article is part of a series ‘As the drain goes’, a joint project by Pinky Chandran, Nalini Shekar, and Citizen Matters, and is supported by the Bengaluru Sustainability Forum (BSF).