At the beginning of this year, the freshly minted electric Yulu bikes were taking their baby steps in Bandra West. The Bangalore-based company had just started branching out of its base in Mumbai, the commercial Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC) district, hoping to become the vehicle of choice for app-based delivery workers.

“Because of COVID-19, home delivery has become so common. There suddenly is an explosion of people saying ‘Why should I go out if I can order in with a few clicks on my phone?’,” Hemant Gupta, co-founder and COO of Yulu/the company had told us, explaining the pivot from last-mile connectivity to delivery. The contactless bikes operate completely through a mobile application and seemed uniquely suited for the similarly operating gig economy.

A little over six months later, the company’s vision seems to have hit the mark. The bikes are now a routine sight on the streets of Bandra West, driven most often by a Zomato, Swiggy or Dunzo delivery partner. The wear from the long hours of use is all too visible, as the shiny and sparkling blue bikes have turned grimy and bruised.

In 2021, Yulu bike estimated 17,000 gig workers across the country to use their bikes. Delivery in Bandra West already made for 35% of their business in Mumbai in January 2022, and is sure to have increased since.

Between a cycle and a bike

Starting out as a last-mile connectivity vehicle, the Yulu bikes work on a pay-as-you-use model. The base fare for the bike in question – the moped-like Yulu Miracle, electric, battery-powered – is Rs 20, with every ride minute costing another Rs 2. But as the company expanded their ambit to include delivery workers, it introduced long-term rental options. The cost for unlimited rides over 7 days is Rs 1,400, each day amounting to Rs 200. At present, this is the only option in Bandra West, effectively narrowing the consumer base to delivery persons.

Fueled by availability, the popularity of the Yulu bike has been driven by the middle ground it offers between a cycle and a scooter or bike.

For those used to doing deliveries on a cycle, the Yulu bikes are an upgrade. They don’t go over 25 km/hr, cancelling the need for a licence and helmet, allowing them to slip past traffic rules and avoid fuel costs. “We can drive on the wrong side of the road and wiggle into small spaces,” says Mujeeb Khan, a delivery worker. “I would get tired doing deliveries on a bicycle because they kept calling us all the way to Mahim and Bandra East.”

Switching to a motorised vehicle, albeit one with less speed, has also helped them increase the number of deliveries they can make with lesser effort. From barely Rs 400-600 earned per day on a cycle, Mujeeb and other drivers comfortably make between Rs 600-800 and over, in a day on the Yulu bike.

Challenges for the Yulu bike

Yet another faction is using the Yulu bikes as a stopgap measure before switching to a more powerful vehicle, like a bike or scooter. Ram Baram started deliveries for Swiggy only 20 days ago, to phase out from his evening job as a cook, hoping for some autonomy. His quibbles with the Yulu bike are minor, including the brakes being ineffectual in the wet and the space inadequate, but these are temporary concerns since he joined Swiggy with the intention of buying a bike soon.

“If I buy a bike, even on a loan which I will have to pay off for the whole year, it will be mine in the end. This will never be mine, even if I pay Rs 6,000 per month forever,” he says. (Plans to sell personal Yulu bikes have been floated for 2023.)

Read more: With the Yulu bike, is Public Bike Sharing in Mumbai picking up?

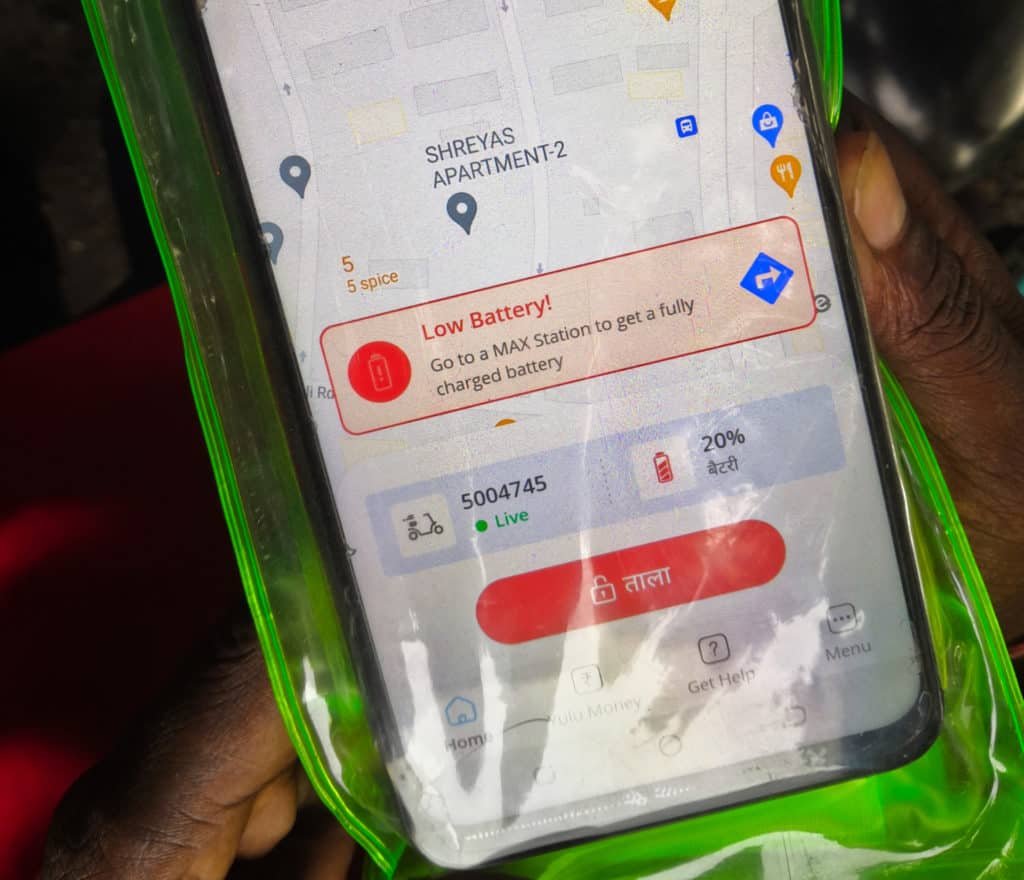

Battery trouble for Yulu Bikes

The Yulu Max station in Pali Naka is one of the three stations the riders can pick up bikes and swap batteries at in Bandra West.

On a Sunday evening, a few drivers are at the gate with their carry bags and Yulu bikes, waiting for their drained batteries to be exchanged with those fully charged. Raghav Choudhary, a driver for Swiggy, has with him an order to deliver. “There are already three other bikes here. Stay for half an hour, and you will see tens more join,” he says.

Raghav, and the other drivers in unanimity, narrate a tale of their everyday struggles at the Max stations. “A battery lasts 4-5 hours, after which we have to come and exchange it at the charging station,” he says. “But there are never any charged batteries waiting for us. We have to wait in lines that go on for two to three hours sometimes.”

This sequence of events takes place two to three times a day, depending on how long the riders work (According to Yulu, a fully charged bike has a range of 50-55 km). The level of charge is visible on the bike’s handlebars and app, but one driver alleges that this is not always accurately reflected, increasing the urgency of swapping the battery when they’re notified to do so. And when they do reach the Yulu Max station, the drivers are often told to go to a different station to try their luck, sometimes even as far as Bandra East.

As a result, the drivers are in different stages of their orders; some have been given a destination for pick up, and others have collected their orders for which the recipients will be waiting. Being stuck in the line for an extended period is laden with the threat of a penalty or time-out from the app, costing them out of their pocket and the daily ride fare.

True to Raghav’s word, more Yulu bikes arrive as the minutes go by. The expectant line extends around the curb of the building, tuned to the routine of the delay. Each driver had the same complaint.

Only a monsoon affair?

The service attendant at the Yulu Max station was not fazed by the drivers trickling in for a battery swap. He gave the first few in the line a wait time of half an hour while checking up on the three charging machines, each with the capacity to charge 12 batteries in four and a half hours. “These lines form many times a day,” he said, wishing to remain anonymous to avoid trouble at his job.

When asked what was behind the delay in serving out batteries, he chalked it up to the monsoon. “We cannot charge a wet battery, or it will cause a short circuit,” he explained. Informing those with higher authority at the company has not led to any changes.

This rationale was met with several objections; Raghav contended the pattern was not new to the season, while Mujeeb argued that an air-blower could cut the drying time short. Another driver said an oft-used excuse was that the machine had stopped working.

Neither is customer service helpful. “They either say they will fix the issue, which they never do, or they’re unresponsive,” said Mujeeb. None of his anger, however, is directed at the service station operator. Instead, it’s concentrated on the company and the various fines and fees they leverage on the delivery workers. As an example, exchanging a dysfunctional bike with over 40 per cent charge costs the rider Rs 40. “Who will compensate us for their shortcomings?” he asks.

Mujeeb talks about getting the other riders together with their grievances to the consumer court. “Most of the drivers here are apprehensive because they don’t know what the consumer court is. But it’s the only option we have.”

Till then, however, it is desperation and the lack of a better choice that drives gig workers to use the Yulu bikes. “I don’t mind if Yulu increases their price by a few hundred. Just give us better battery service,” says Raghav.