2021 saw Bengaluru’s public healthcare systems totally collapsing in the face of the second wave of COVID-19. What could the city have done better? What needs to change? In this article, public health researcher Adithya Pradyumna puts out his wishlist for public healthcare in the city for the new year. Adithya is a co-author of the report ‘Health Care Equity in Urban India’, published this December. The report was based on a project undertaken this year by Adithya and his colleagues from Azim Premji University, which also included a case study of Bengaluru.

Urban healthcare in India is generally messy. Take Bengaluru, for instance, where several players are offering services at various levels for different sections of the population. Public health care services include those provided by the state government’s Department of Health and Family Welfare (community-based care to tertiary care), those by the BBMP (community-based care to secondary care, and also on determinants such as sanitation, water and drainage), the Employees State Insurance scheme or ESI (primary care to tertiary care for those registered under the scheme), AYUSH (primary care to tertiary care), and Central Government Health Services or CGHS (primary care to tertiary care for central government employees).

Additionally, any number of private and charitable institutions are offering primary to tertiary care across the city, which can be accessed by paying out-of-pocket or through insurance schemes in some situations.

During the course of our project, our attempts to speak with health officials in Bengaluru to better understand the city’s health system failed. But we were able to have extensive discussions with community-based government health workers and representatives of civil society organisations in Bengaluru. I will draw my wish list based on the problems identified by these constituencies in particular, and based on our general observations about urban healthcare in India.

Some of these are chronic challenges, and some of these are acute exacerbations due to COVID-19 and the response to it. I have several wishes for public healthcare in Bengaluru, but I’ll just mention a few of them here.

- Strengthen the community connect

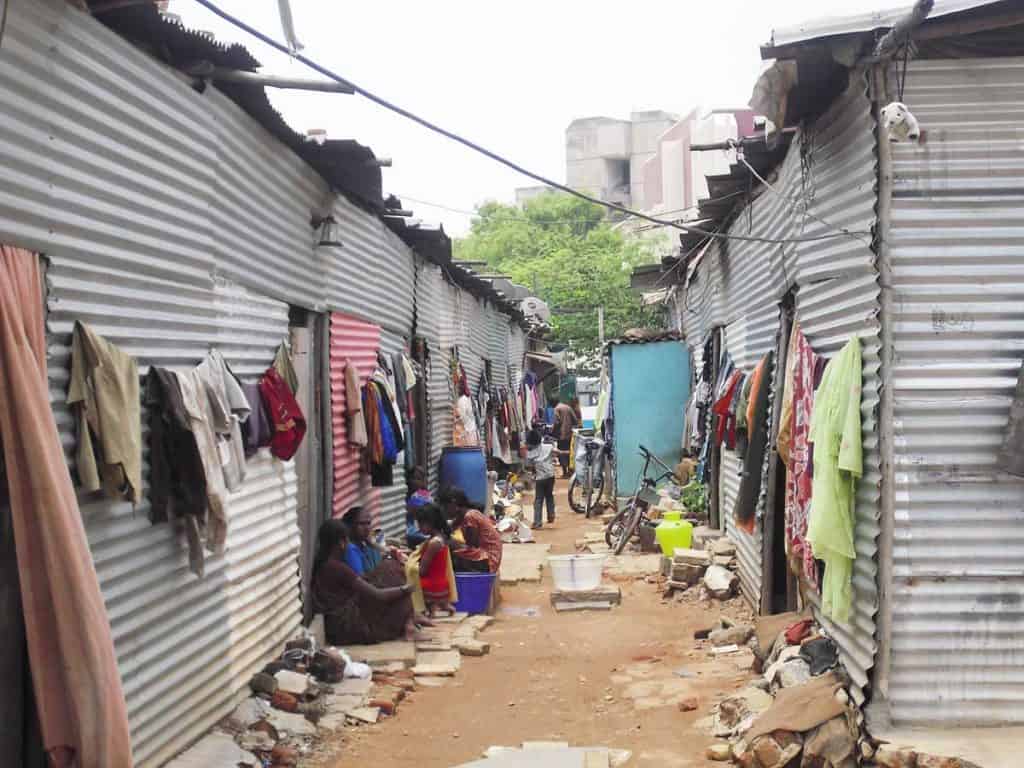

My first wish is the strengthening of the community connection of the health system. The groups identified as most vulnerable in urban areas included the recent in-migrant population in urban poor settlements, especially young women, rag pickers, homeless individuals and families, and sexual minorities.

Read more: “A digitised card cannot solve problems of access and affordability in public health”

During our conversation with community-based organisations, we learned it was due to their familiarity with the community that they were able to respond to acute crises such as during the first COVID lockdown in 2020. With COVID, public healthcare systems had diverted their focus to COVID, and the primary healthcare needs of vulnerable populations were neglected.

Community-based organisations knew the location of vulnerable households, and their healthcare and other needs. For example, groups working with rag pickers were able to reach out to them and support them. The organisations identified their intimate knowledge of the community as important and valuable. So this should become a regular feature of our health services.

Other mechanisms such as community-based health kiosks and thoughtfully-planned community outreach activities also helped strengthen community connect. These should function optimally even without the intervention of community-based organisations. This relates to the need to improve accountability mechanisms for healthcare entitlements – that is, ensuring that what is promised is delivered, with spaces for feedback and actions to address concerns and gaps.

- Government should support its community health workers better

During our conversation with government-appointed health workers such as ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists) and community-based nurses, we learned how they engage on a day-to-day basis with the health needs of vulnerable populations. They form the first line of contact, and are in a position to address basic requirements and guide people to appropriate healthcare based on their needs.

It is in that context that I come to my second wish, that community health workers should be better supported to do their work. We saw, and continue to see, that these workers are critical not just in regular times, but also during crises. During COVID-19, they have also faced discrimination from the community, and have had to work through these challenges.

However, they are burdened with ever-increasing work based on new programmes and technologies that come in, while also being paid inadequately. Health workers also identified the need for better capacity to do their work, which would involve a stronger technical foundation to understand their work, and programmatic support. Hope their needs are acknowledged and addressed.

- Government doctors should be more empathetic

My third wish is that doctors in our governmental hospitals become more sensitive and empathetic. This was specifically identified as a challenge by a few of the government-appointed community health workers we interviewed.

Patients using government health services are vulnerable as it is, so it becomes crucial that the health system does not give them more reasons to shy away from seeking the care that they need and are entitled to. It is understandable that doctors are also stretched due to major shortfalls in personnel, and this points to another important need, that of better funding for urban healthcare.

Read more: Opinion: How ‘privatisation’ and ‘PPP models’ have left Indians to die

- Improve social and environmental determinants of health

My final wish in this short wish list is that healthcare personnel and BBMP take leadership in improving the social and environmental determinants of health in Bengaluru. Health workers themselves told us about the need for better sanitation and cleanliness in urban poor settlements. This is already in line with the thinking at various levels of leadership to improve sanitation in India. So there should be no delay in measures to improve community sanitation in vulnerable areas.

In addition, health workers at various levels should advocate for better air quality. Air pollution is one of the most important determinants of health in India, and Bengaluru has very poor air quality. Health workers should advocate for clear air and protection of green spaces and waterbodies, while transforming hospitals and health systems to be eco-sensitive (for instance, through waste reduction and energy efficiency). A better environment will greatly reduce the burden on healthcare services, and also help the children of the city grow up in a healthy environment as they deserve.

Acknowledgements: Many insights in this article are based on the report ‘Health Care Equity in Urban India‘ authored by Arima Mishra, Shreelata Rao Sheshadri, Adithya Pradyumna, Edward Premdas Pinto, Aruna Bhattacharya, and Prasanna Saligram, all of whom are faculty members at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. Thanks to Arima for also reviewing a draft version of this piece.

I agree with most of the points suggested.and especially Community connection and taking care of CHWs by government