If all goes well, the bulk of Bangalore’s Public Transport commuters will be moving in trains over rail tracks rather than on roads by around 2032. Plans that have been pending for long are finally being implemented to expand Metro and add Suburban Rail to cover large parts of the city with a combined urban rail network totalling over 400 km.

Bengaluru’s quest for rail-based solutions began close to 40 years ago in 1983 when a Commuter Rail system was first proposed. Since then, road traffic has grown by leaps and bounds as street-based transport has remained the only option, even as BMTC buses became inefficient, unreliable and unpredictable due to increasing traffic congestion.

Bus transport getting defeated by traffic congestion

Bus commuters increasingly have moved to two-wheelers, cars and other more nimble vehicles of all sizes including door-to-door taxis that can be hailed over a mobile phone. Wrestling to gain advantage on streets with vehicles jostling for space has thus reached alarming proportions.

No matter how excellent the supply side of public transport may be, services can only have as much quality and punctuality as traffic conditions will allow. This aspect is being overlooked when calls are being made to increase bus services multi-fold to address public transport deficiencies.

At the same time, buses do have enormous reach as city road networks are vast. Hence buses have an important role to play since tracks can’t be built everywhere for trains since they require a lot of space and are far more capital intensive.

Read more: Raja Rajeshwari Nagar may have Namma Metro, but poor last-mile connectivity discourages commuters

Topping in traffic congestion

News reports have suggested that the total number of motorised vehicles in the city would be well over 10 million in 2022. The number of motorised vehicles in the city was 2.64 million in 2008. This had shot up to over 8 million by 2019 at an average CAGR rate of growth of 10.32. If this trend were to continue, the city will have over 14.5 million vehicles by 2025 itself.

Read more: “Namma Metro till Silk Institute saves me Rs 10,000 a month”

Putting rail-based transport on track

The expansion of Metro and the development of a Suburban Rail system on dedicated tracks are steps that were long overdue. These steps are now being taken (finally) by the government in an attempt to shift public transport users off the streets onto exclusive track systems for faster commutes.

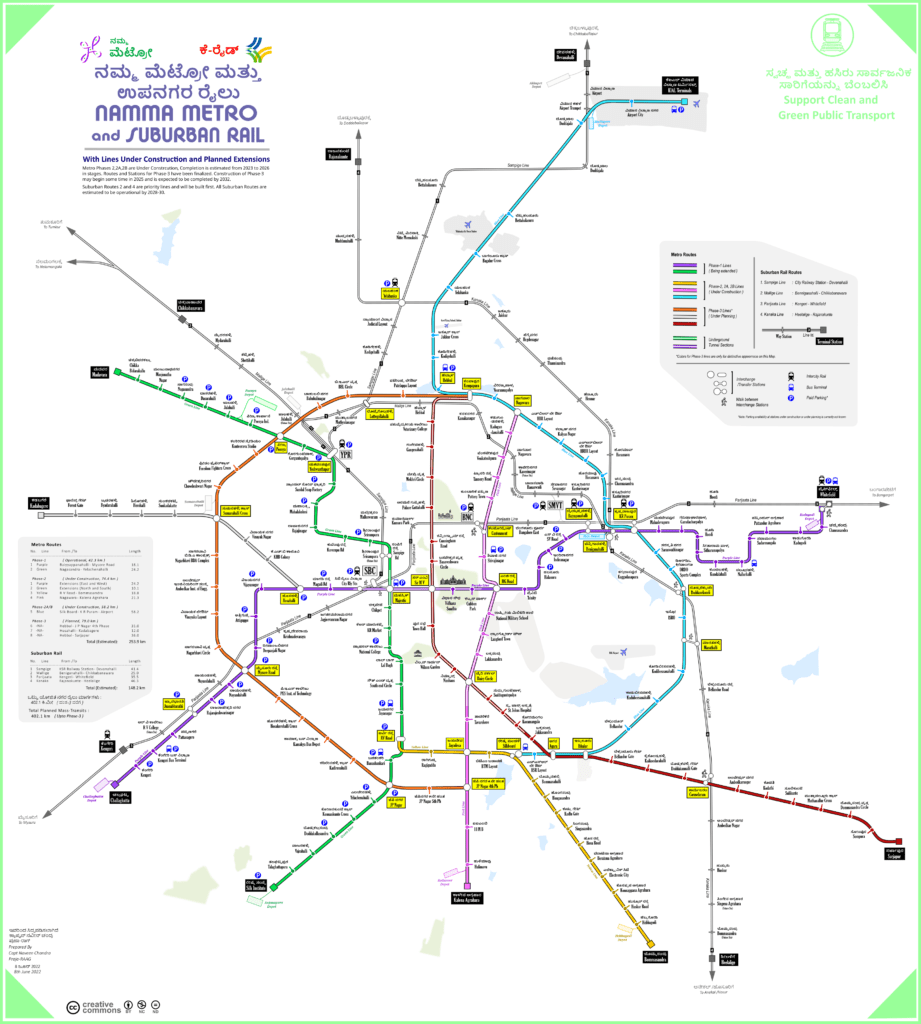

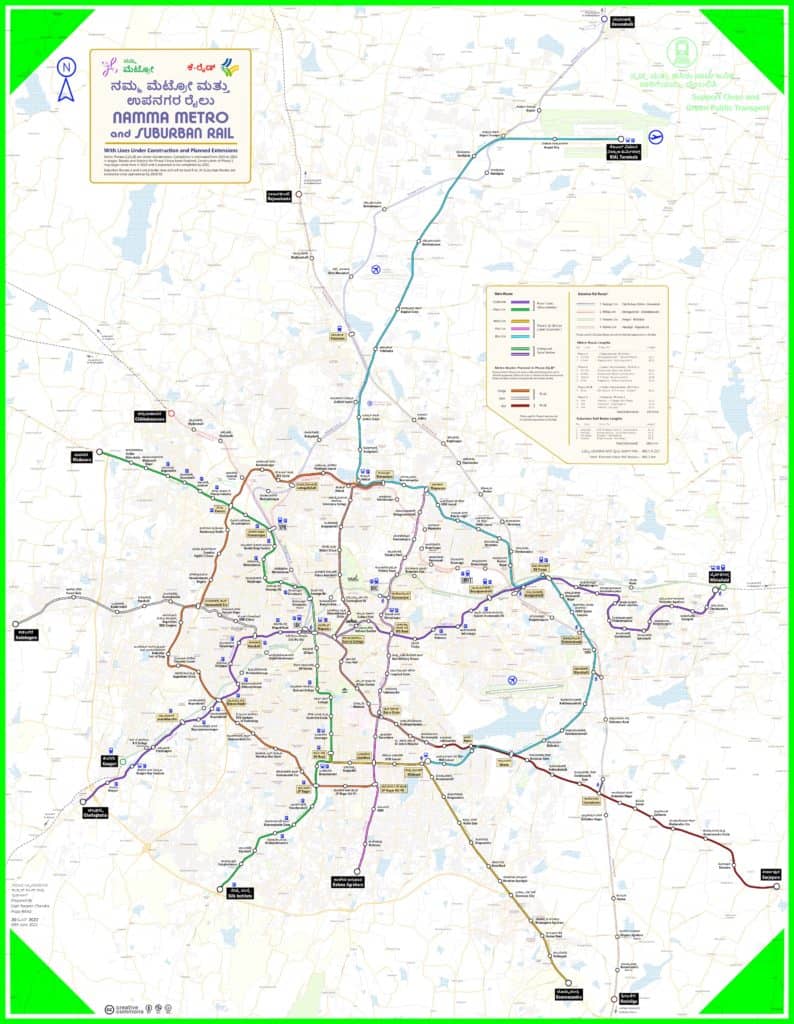

During Phases 2 and 3, Metro is likely to add 211.6 km to the existing 42.3 km that has been in operation since 2017 (built under Phase 1). About 14 km under Phase 2 has been commissioned in 2021. Thus, 56.1 km is currently operational. Two new lines are expected to be commissioned by 2024-25 and the Airport line is likely to get ready by 2026-27.

Rail networks to reach most corners of Bengaluru

Metro’s Phase-3 routes and stations have been announced and Detailed Project Reports (DPR) are under preparation. It is likely that construction may begin by 2025 with an estimated completion target of 2032. Route selections appear reasonably good to cover most parts and activity centres.

As is clear from the maps, the Metro network will have eight lines. Two lines would be aligned around the circle of the Outer Ring Road. The remaining six routes are mostly radial and will have intersections with the Ring line/s (some lines will intersect at multiple points). The three North-South Metro lines will provide easy access to central CBDs as they cut through the city’s central areas. The four Suburban routes will supplement the Metro system and offer faster commutes over longer distances (thus, it will more or less be an ‘express’ mass transit system with much fewer halts than the metro). The existing East-West metro Line (Purple line) will in future be supplemented by the Parijaata Suburban Line that deviates from the Purple line’s route when within ORR but converges outside ORR at both ends.

It is hoped that the onslaught of motorisation will slow down, if not halt once these extensive rail-based travel options are made available. Road expansions need to be minimized; just enough to take care of necessities to operate buses or reach public transport, particularly in peripheral areas where the secondary and tertiary road networks are in poor condition and also to assist commuters to reach trains easily.

Read more: How are India’s metro rail systems faring?

Expanding to multimodal transport

The city’s transition from predominantly street-based vehicles to one that is rail-based for commutes is going to throw up several challenges. No matter how much urban rail is built, it can never match the volume of roads in a city and all rail commutes will most certainly involve streets for the last mile and pedestrian paths for the final lap of any commute in most cases.

Thus the emphasis on buses, taxis, auto-rickshaws and parking availability close to train stations would be a necessity. Arranging multi-modal transfer facilities is a formidable task as multiple agencies would be involved, but it has to be done, no matter what, to attract commuters to trains being built with huge investments.

The next ten years are going to see vast changes in travel habits in the city after a long period of uncertainty and debates for solutions when commuters were largely left in the lurch!